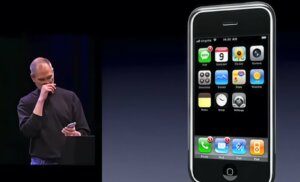

Torvalds chiude l’era dell’hype: nel kernel Linux conta solo la qualità, non l’IA

Redazione RHC - 11 Gennaio 2026

Nasce SimpleStealth: il malware invisibile per macOS creato dalle AI

Redazione RHC - 11 Gennaio 2026

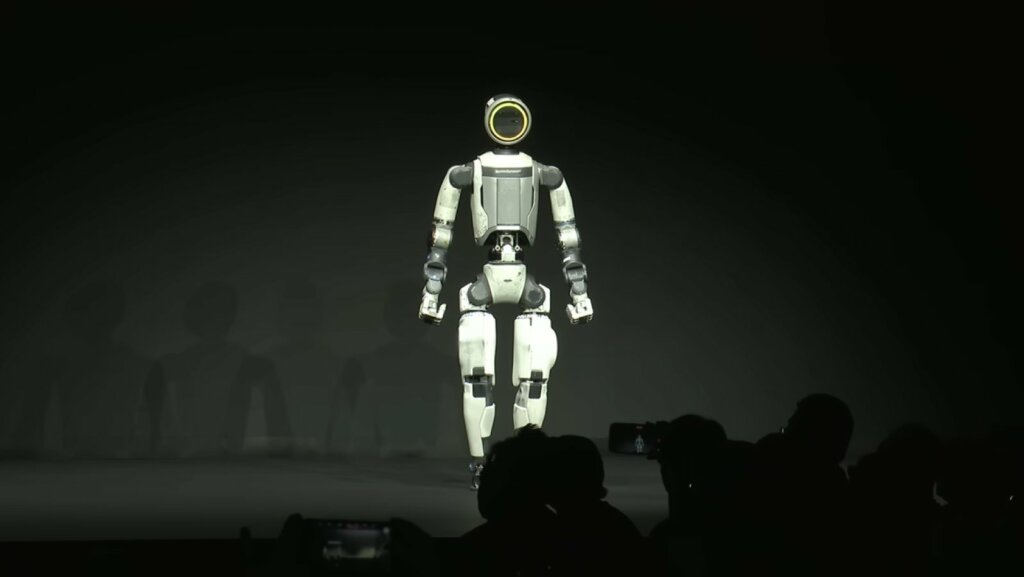

Boston Dynamics presenta Atlas, il robot umanoide

Redazione RHC - 11 Gennaio 2026

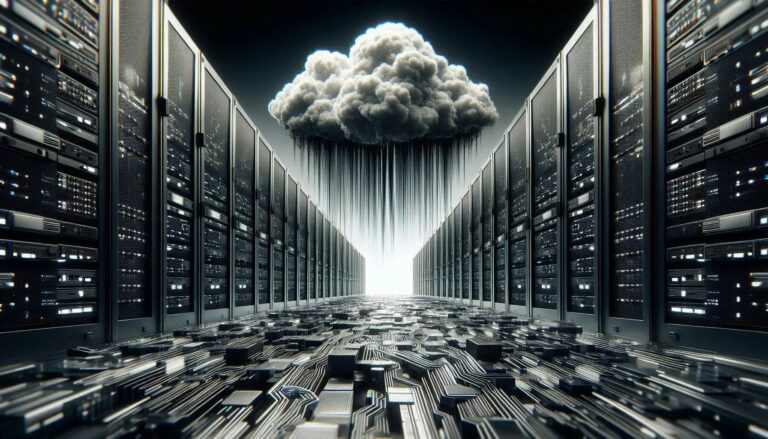

Caso AGCOM Cloudflare. Il Cloud è potere: quando la sicurezza nazionale è in mano alle Big Tech

Redazione RHC - 11 Gennaio 2026

Internet c’è, ma non funziona: la nuova trappola dei governi per controllarci tutti

Redazione RHC - 11 Gennaio 2026

Doom sbarca in pentola: il leggendario sparatutto ora gira su una pentola a pressione

Redazione RHC - 10 Gennaio 2026

LockBit torna a colpire: la nuova versione 5.0 rilancia il ransomware più temuto

Redazione RHC - 10 Gennaio 2026

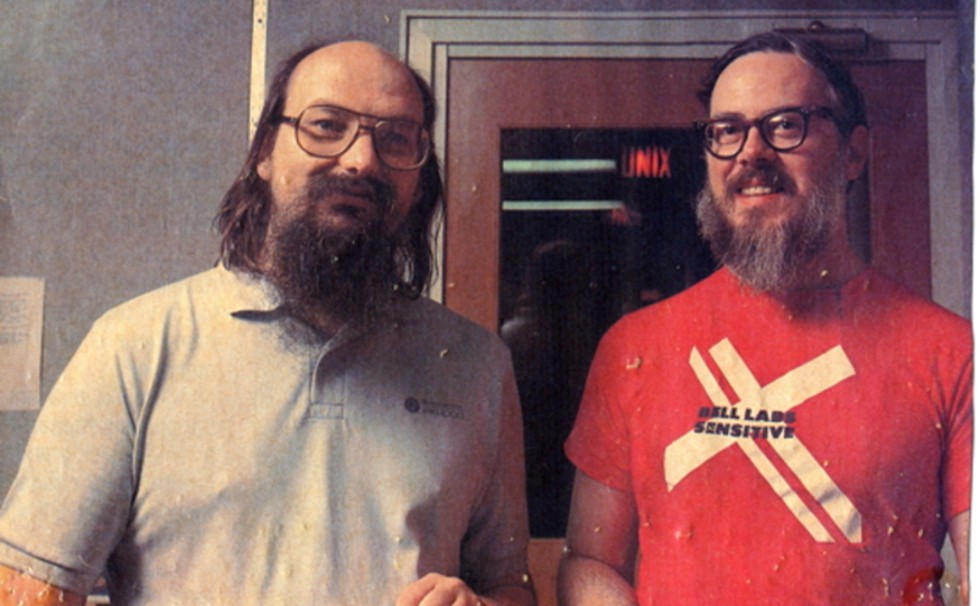

Ritrovato dopo 50 anni: il raro nastro UNIX V4 rivive al Computer History Museum

Redazione RHC - 10 Gennaio 2026

La maxi-fuga di dati che spaventa Instagram: 17,5 milioni di profili circolano nel DarkWeb

Redazione RHC - 10 Gennaio 2026

“La tua password sta per scadere”: quando il phishing sembra arrivare dall’ufficio della porta accanto

Redazione RHC - 10 Gennaio 2026

Ultime news

Torvalds chiude l’era dell’hype: nel kernel Linux conta solo la qualità, non l’IA

Nasce SimpleStealth: il malware invisibile per macOS creato dalle AI

Boston Dynamics presenta Atlas, il robot umanoide

Caso AGCOM Cloudflare. Il Cloud è potere: quando la sicurezza nazionale è in mano alle Big Tech

Internet c’è, ma non funziona: la nuova trappola dei governi per controllarci tutti

Doom sbarca in pentola: il leggendario sparatutto ora gira su una pentola a pressione

Scopri le ultime CVE critiche emesse e resta aggiornato sulle vulnerabilità più recenti. Oppure cerca una specifica CVE

Ricorrenze storiche dal mondo dell'informatica

Articoli in evidenza

Cultura

CulturaLinus Torvalds, il creatore di Linux, ha espresso una posizione ferma e senza mezze misure riguardo al dibattito sull’integrazione e l’uso di strumenti di intelligenza artificiale nella scrittura e revisione del codice del kernel di…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNel mondo di oggi la tecnologia non è più un mero strumento di efficienza o comodità, ma una leva geopolitica di primaria importanza. L’accesso a infrastrutture digitali, piattaforme cloud e sistemi di comunicazione non è…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeImmaginate una situazione in cui Internet sembra funzionare, ma i siti web non si aprono oltre la prima schermata, le app di messaggistica sono intermittenti e le aziende sono in continuo cambiamento. Secondo gli autori…

Cultura

CulturaRecentemente, una bobina di nastro magnetico è rimasta in un normale armadio universitario per mezzo secolo, e ora è improvvisamente diventata una scoperta di “archeologia informatica del secolo“. Un nastro con la scritta “UNIX Original…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeUn massiccio archivio digitale contenente le informazioni private di circa 17,5 milioni di utenti Instagram sembrerebbe essere finito nelle mani dei cybercriminali. Qualche ora fa è stato segnalato l’allarme dopo che diversi utenti su Reddit…