I sistemi di intelligenza artificiale sono stati criticati per aver creato report di vulnerabilità confusi e per aver inondato gli sviluppatori open source di reclami irrilevanti. Ma i ricercatori dell’Università di Nanchino e dell’Università di Sydney hanno un esempio del contrario: hanno presentato un agente chiamato A2, in grado di trovare e verificare le vulnerabilità nelle applicazioni Android, simulando il lavoro di un bug hunter. Il nuovo sviluppo è la continuazione del precedente progetto A1, che era in grado di sfruttare i bug negli smart contract.

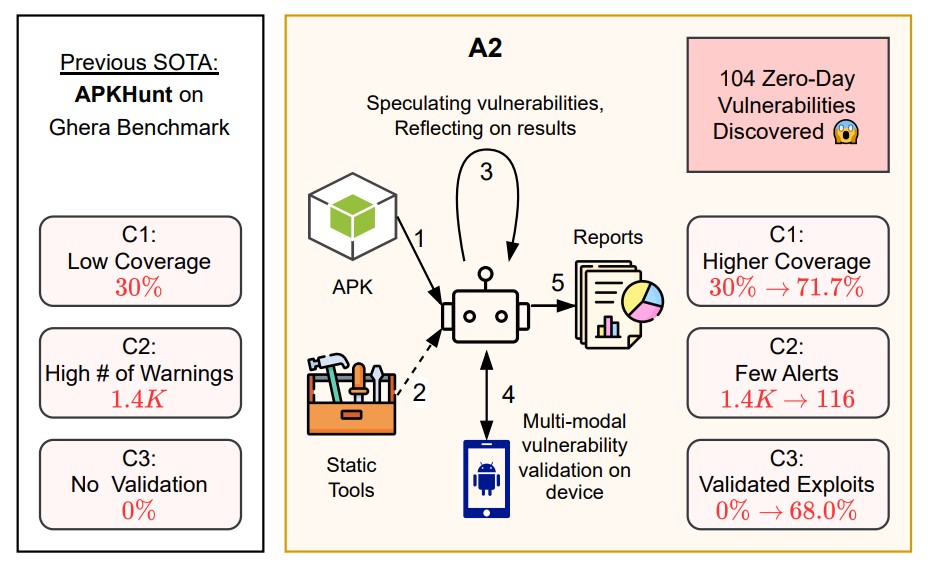

Gli autori affermano che A2 ha raggiunto una copertura del 78,3% sulla suite di test Ghera , superando l’analizzatore statico APKHunt, che ha ottenuto solo il 30%. Eseguito su 169 APK reali, ha rilevato 104 vulnerabilità zero-day, di cui 57 confermate da exploit funzionanti generati automaticamente. Tra queste, un bug di media gravità in un’app con oltre 10 milioni di installazioni. Si trattava di un problema di reindirizzamento intenzionale che ha permesso al malware di prendere il controllo.

La caratteristica distintiva principale di A2 è il modulo di convalida, assente nel suo predecessore.

Il vecchio sistema A1 utilizzava uno schema di verifica fisso che valutava solo se un attacco avrebbe portato profitto. A2, invece, è in grado di confermare una vulnerabilità passo dopo passo, suddividendo il processo in attività specifiche. A titolo di esempio, gli autori citano uno scenario con un’applicazione in cui la chiave AES era memorizzata in chiaro. L’agente trova prima la chiave nel file strings.xml, quindi la utilizza per generare un token di reimpostazione della password falso e infine verifica che questo token bypassi effettivamente l’autenticazione. Tutte le fasi sono accompagnate da verifica automatica: dalla corrispondenza dei valori alla conferma dell’attività dell’applicazione e alla visualizzazione dell’indirizzo desiderato sullo schermo.

Per funzionare, A2 combina diversi modelli linguistici commerciali : OpenAI o3, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Gemini 2.5 Flash e GPT-oss-120b. Sono distribuiti in base ai ruoli: il pianificatore elabora una strategia di attacco, l’esecutore esegue le azioni e il validatore conferma il risultato. Questa architettura, secondo gli autori, riproduce la metodologia umana, il che ha permesso di ridurre il rumore e aumentare il numero di risultati confermati. Gli sviluppatori sottolineano che gli strumenti di analisi tradizionali producono migliaia di segnali insignificanti e pochissime minacce reali, mentre il loro agente è in grado di dimostrare immediatamente la sfruttabilità di un errore.

I ricercatori hanno anche calcolato il costo del sistema. Il rilevamento delle vulnerabilità costa tra 0,0004 e 0,03 dollari per app utilizzando modelli diversi, mentre un ciclo completo con verifica costa in media 1,77 dollari. Allo stesso tempo, se si utilizza solo Gemini 2.5 Pro, il costo aumenta a 8,94 dollari per bug. A titolo di confronto, l’anno scorso un team dell’Università dell’Illinois ha dimostrato che GPT-4 crea un exploit a partire dalla descrizione di una vulnerabilità per 8,80 dollari. Si scopre che il costo per individuare e confermare le falle nelle app mobili è paragonabile al costo di una vulnerabilità di media gravità nei programmi bug bounty, dove le ricompense sono calcolate in centinaia e migliaia di dollari.

Gli esperti sottolineano che A2 supera già le prestazioni degli analizzatori statici di programmi Android e A1 si avvicina ai migliori risultati negli smart contract. Sono fiduciosi che questo approccio possa accelerare e semplificare il lavoro sia dei ricercatori che degli hacker, perché invece di sviluppare strumenti complessi, è sufficiente richiamare l’API di modelli già addestrati. Tuttavia, rimane un problema: i cacciatori di ricompense possono utilizzare A2 per un rapido arricchimento, ma i programmi di ricompensa non coprono tutti i bug. Questo lascia delle scappatoie per gli aggressori che possono utilizzare direttamente gli errori trovati.

Gli autori dell’articolo ritengono che il settore stia appena iniziando a svilupparsi e che ci si possa aspettare un’impennata di attività sia negli attacchi difensivi che in quelli offensivi nel prossimo futuro. I rappresentanti del settore sottolineano che sistemi come A2 spostano le ricerche di vulnerabilità da allarmi infiniti a risultati confermati, riducendo il numero di falsi positivi e consentendo di concentrarsi sui rischi reali.

Per ora, il codice sorgente è disponibile solo per i ricercatori con partnership ufficiali, per mantenere un equilibrio tra scienza aperta e divulgazione responsabile.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…