Redazione RHC : 8 July 2025 09:27

Today I would like to bring to light a revolutionary essay, a source of inspiration for many scientists who have contributed to technological innovation, especially in computer science in the years to follow.

This essay was written in 1945 by Vannevar Bush, published by the magazine The Atlantic Monthly and introduced science to a new way of conceiving things, making it clear that for years, all inventions have only taken into consideration the extension of man’s physical powers, rather than the powers of his mind.

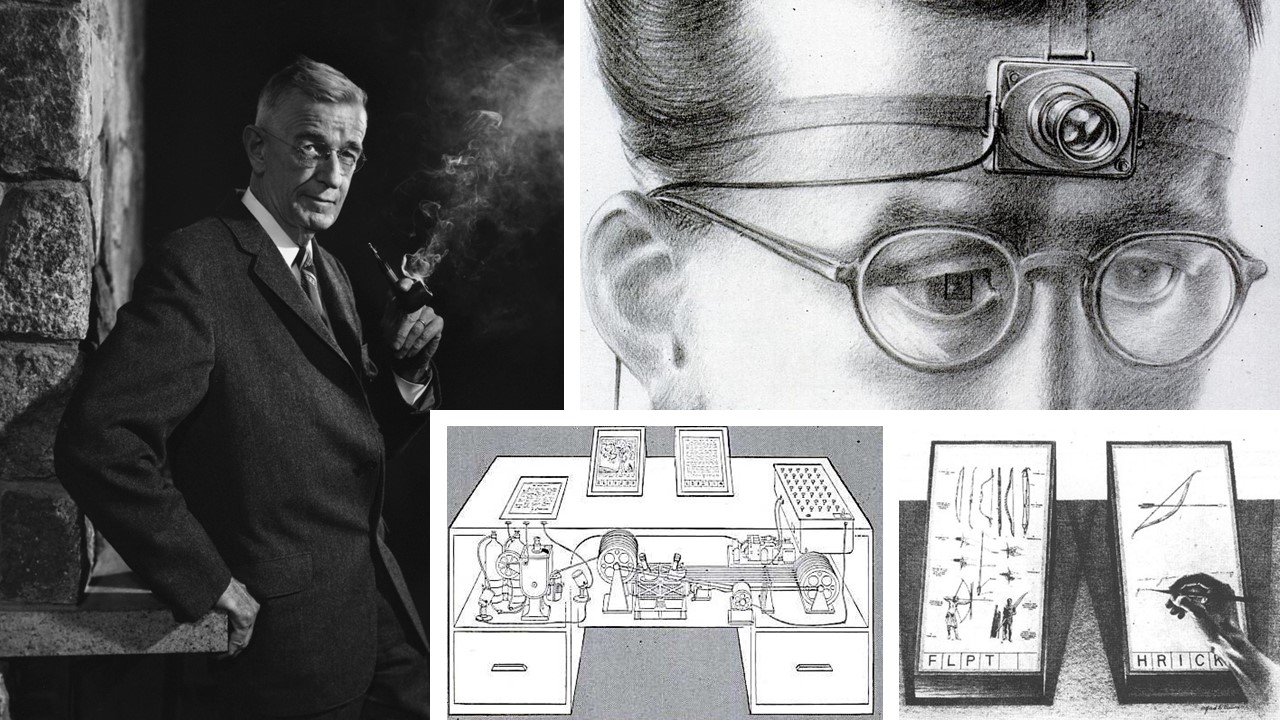

Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush was an American engineer, born March 11, 1890, vice president of MIT and holder of many patents on analog computers, as well as being the inventor of the differential analyzer.

From 1945 he directed the Office of Research and Development scientific of the United States of America, the body that developed numerous researches in the military field, such as radar, as well as the control of the Manhattan Project, the project that allowed the production of the first nuclear bombs.

He wrote an essay in 1945 entitled “As We May Think” which was published in July by the magazine The Atlantic Monthly, as well as being republished in a shorter version in September of the same year, practically at the time of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Cover of the essay “As We May Think”

Bush expressed concern about the direction of scientific efforts toward mass destruction, rather than understanding, and explained the desire and need for some kind of – collective memory machine – with the enormous potential to make knowledge more accessible to all, as well as answer the question

“How can technology contribute to the well-being of humanity?”

The essay bases its reasoning on a premise:human knowledge is a set of connected knowledge and has a universal dimension that cannot be limited to the life of the individual.

Knowledge is the result of a continuous process, built thanks to a fruitful collaboration between scientists and includes the heritage of all that human knowledge, where access to scientific information is a necessary condition for the growth of the human race.

In fact, it was not a mere technical question, the topic of the essay was mostly a strong philosophical and political reflection on how knowledge is produced and communicated.

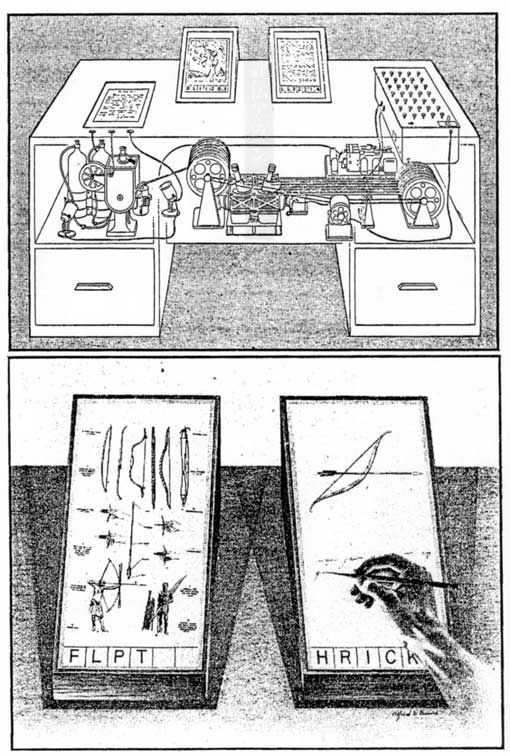

Bush, in section 6 of the 8 in the essay, presents the “memex”, a sort of extension of human memory in the form of a mechanical desk that contained a microfilm archive inside, which would have been the storage medium for storing books, registers and documents to be able to later reproduce them and associate them with each other.

The Memex at the top and the two screens at the bottom.

The memex takes its name from “memory extender” and is essential because Bush says that

“The human mind works by association. With an object in hand, it instantly jumps to the next one suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with an intricate network of traces carried by the cells of the brain”

The memex in fact helps the researcher to remember things more quickly, in addition to being able to quickly see their information archives by typing the code of the register and the book, iso as to be able to recall and view it immediately on one of its visors.

The interface was simple, consisting of buttons and simple levers.

Moving the lever to the right takes you to the next page, while moving it even further to the right will scroll 10 pages at a time, obviously moving it to the left will have the same functionality but in reverse, while a special button allows repositioning to the first page of the book.

Furthermore, the memex user could have opened multiple books at the same time, perhaps on the same topic, effectively creating a path and connections between the information, effectively defining a new book, as well as taking notes thanks to a high-resolution photography technology dry.

With this essay, Bush strongly anticipates what we will see a few decades later on the world wide web, in addition to revolutionizing the concept of workstation by introducing page-by-page navigation through connections and links.

This essay fundamentally inspired the subsequent innovations of the oN-Line-System, the operating system created by Dug Engelbart, presented in the “Mother of all demos” of 1968 which we talked about in a previous article on Red Hot Cyber.

Sources

Redazione

Redazione