A new wave of digital deception has hit the Microsoft Azure ecosystem, where newly discovered vulnerabilities have allowed cybercriminals to create malicious apps that perfectly mimic official services like Microsoft Teams or the Azure Portal . These “fake” applications are identical to the originals, capable of deceiving even experienced users.

The discovery, made by researchers at Varonis , revealed that Azure security measures designed to block sensitive names could be bypassed using invisible Unicode characters. By inserting characters like the Combining Grapheme Joiner (U+034F) between letters, such as in “Az͏u͏r͏e͏ ͏P͏o͏r͏t͏a͏l” , attackers were able to register apps that appeared legitimate but were interpreted by the system as different. This insidious trick, working with over 260 Unicode characters, allowed the creation of “cloned” apps with sensitive names such as Power BI or OneDrive SyncEngine .

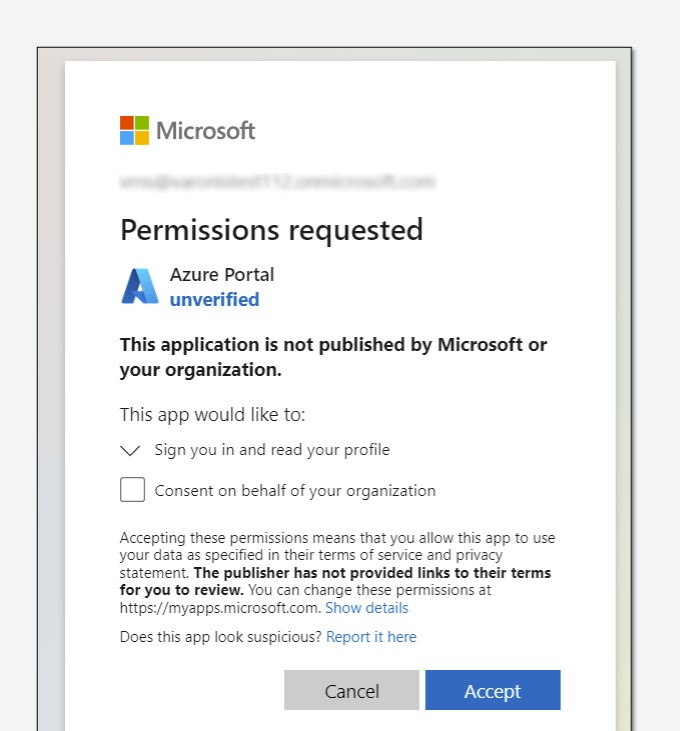

The real strength of this attack lay in its visual deception: the consent pages of the fake apps appeared authentic, often accompanied by Microsoft icons and logos. Many apps, in fact, didn’t display any verification badges, and users, seeing familiar names, ended up ignoring the “not verified” warnings and granting full permissions.

From there, the second phase began: carefully crafted phishing emails directed victims to spoofed consent pages, where simply clicking “Accept” granted valid access tokens without even entering a password. In other cases, attackers used so-called device passcode phishing, generating a legitimate verification code for a malicious app and convincing the victim to enter it on a seemingly secure portal. Within seconds, the session was hijacked.

Those who work in Microsoft 365 environments know the power of application and delegated consents: the former allow an app to act on behalf of the user, the latter grant autonomous access to resources. In the wrong hands, these permissions become tools for initial access, persistence, and privilege escalation, paving the way for large-scale compromises.

After the report, Microsoft fixed the Unicode bypass bug in April 2025 and closed further variants in October 2025. Patches were distributed automatically, without requiring direct intervention from customers. However, Varonis researchers emphasize that consent monitoring, enforcement of the principle of least privilege, and user training remain essential to mitigating the risk.

This episode demonstrates once again that social engineering remains cybercriminals’ most effective weapon. Complex exploits aren’t necessary when a perfectly imitated login page and a familiar name are enough to convince someone to click. In the cloud world, trust can be a double-edged sword: a seemingly innocuous consent can open the doors to the entire tenant and seriously compromise the security of the Microsoft 365 environment.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.