As we know, there are different types of cybercriminals. There are ethical hackers and criminal hackers. Within criminal hackers, there are a multitude of dimensions, including, specifically, nation-state-funded hacker groups (or advanced persistent threat (APT) groups) that carry out cyberattacks to gain an advantage, ranging from financial gain to intellectual property.

Today we’ll talk about a well-known National State group, said to be affiliated with the Russian government, specifically the GRU, the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces. This is a military intelligence agency that operates and controls its own special forces and units. Today we’ll talk about SandWorm.

This highly resourceful group primarily targets the Russian Federation’s neighbors, such as Ukraine, Estonia, and Georgia. It is commonly referred to and recognized by the US, UK, and NATO as Sandworm and is responsible for some of the most horrific cyber attacks in recent years. Attacks such as NotPetya, Industroyer /Crash Override, Bad Rabbit, and Olympic Destroyer have all been attributed to Sandworm.

Its tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) overlapped with another well-known Russian cyberespionage group, the infamous FancyBear,

But what makes Sandworm so terrifying is its propensity to target industrial control systems (ICS) and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) software. This type of software is used in the energy sector, hospitals, water treatment plants, manufacturing, telecommunications, and transportation, among other utilities.

Stuxnet was allegedly developed by US and Israeli intelligence agencies and launched in 2010, although it is believed to have been in development since at least 2005. Stuxnet targets Siemens ICS, SCADA, and programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and is responsible for causing substantial damage to the Iranian nuclear program. It was highly sophisticated malware that contained four zero-day vulnerabilities that were revealed after code analysis.

The rest of the world was shocked by the destructiveness of a cyberattack on such heavily defended nuclear power plant networks, as well as by the cyber capabilities possessed by the United States. Probably spurred by this event, Russia began its research and development on such cyberweapons, including zero-day vulnerabilities and malware specifically targeted at ICS systems.

On December 23, 2015, Kyivoblenergo (also known as Ukrenergo), a regional electricity distribution company in Ukraine, reported customer service disruptions. This was due to a cyberattack using the BlackEnergy malware, linked to this GRU hacker team.

Researchers at the American cybersecurity firm FireEye were responsible for the name after reverse engineering and decrypting the BlackEnergy malware recovered from the Ukrenergo attacks. The name “Sandworm” comes from a piece of code in the malware that attackers could use to track victims.

One reference within the malware was named “arrakis02,” followed by several others. All were references to Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel Dune. In the Dune universe, giant sandworms live beneath the surface, similar to hackers who invade networks.

John Hultquist, now Lead Intelligence Analyst at FireEye, decided that Sandworm was a fitting name for such a terrifying hacker targeting civilian infrastructure.

Further wiper malware attacks have rocked Ukraine after Sandworm (also known as Telebots, introduced by ESET) continued to use BlackEnergy and its wiper malware, Killdisk, to destroy data in a series of targeted attacks against government institutions and media companies.

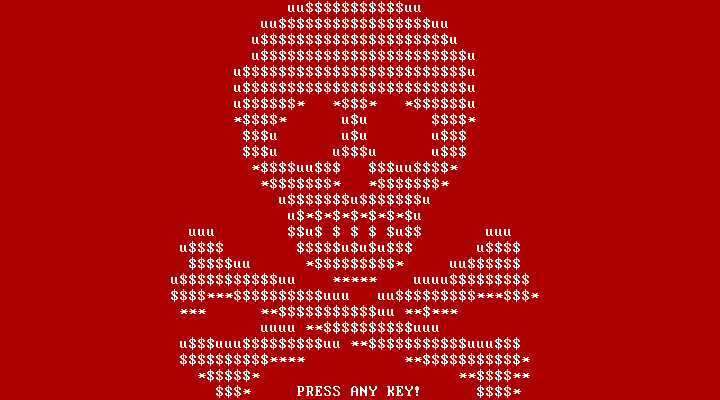

During some attacks, the hackers depicted themselves in an image (shown in Figure 1), which was reminiscent of the Amazon Prime TV series Mr. Robot, as hacktivists rather than an APT group. Interestingly, in the Mr. Robot TV series, the hackers deployed malware on a global banking conglomerate called EvilCorp, wiping out everyone’s debts and throwing the global economy into chaos.

This was in fact very similar to the NotPetya ransomware attack which cost the international community a whopping $10 billion, and stands as the single most expensive cyber attack in history.

A year later, on December 17, 2016, the Ukrainian capital, Kiev, suffered a blackout. Local investigators later confirmed that the power outage was caused by a cyberattack.

The malware was Industroyer, (but it is also known as Crash Override) , which targeted ICS, making it the second cyber threat in history, since Stuxnet.

This was a landmark incident in the history of cyber attacks, as it confirmed that Russia possesses the same capabilities as the United States, but used them on Ukrainian civilian infrastructure, unlike an Iranian nuclear weapons procurement facility.

Kiev’s power grid was offline for six hours before being manually restored by engineers. This incident sent a message to the rest of the world that Russia’s cyber offensive capabilities were a force to be reckoned with.

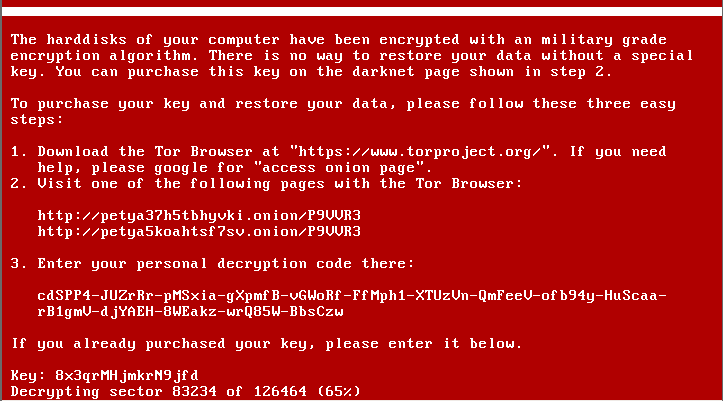

Six months after the Industroyer events, the NotPetya ransomware was launched against Ukraine and other organizations around the world.

Tens of thousands of systems in more than 65 countries were affected , including those belonging to major companies such as Rosneft, Maersk, Merck, FedEx, Mondelez International, Nuance Communications, Reckitt Benckiser, and Saint-Gobain. The largest concentration of victims was in Ukraine , at the headquarters of a tax software company, ME Doc, whose update server was used as the initial infection vector .

Ukrainian government institutions, public transport, banks, and even the Chernobyl site were all put out of service.

NotPetya’s voracity stemmed from its ability to spread and encrypt the master boot record (MBR) of Windows systems across entire networks, leaving them functionally disabled.

Similar to WannaCry, NotPetya abused NSA hacking tools leaked by Shadow Brokers in 2016. This includes the EternalBlue vulnerability and the Doublepulsar backdoor .

When combined with Mimikatz, a tool capable of harvesting credentials from system memory, NotPetya could enumerate entire networks in minutes.

Even after the devastating NotPetya attacks, Sandworm continued its activities and launched further ransomware attacks involving a new variant known as Bad Rabbit . ESET researchers discovered that it primarily targeted Ukraine, but also parts of Russia.

Bad Rabbit targeted Odessa Airport and the Kiev Metro, causing them to close and suspend services. It was later discovered that Bad Rabbit was distributed via watering hole attacks with a fake version of Adobe Flash Player that contained the ransomware.

After months of silence, during the opening ceremony of the 2018 South Korean Winter Olympics, Kremlin hackers reportedly struck again. This time, they used malware called Olympic Destroyer after deleting the main domain controllers used by the South Korean Olympic Committee during the countdown to the opening ceremony.

Initially, due to the increased number of false flags present in the malware , security researchers were unsure who was behind this attack. Some mistakenly attributed it to North Korea or China due to reused code fragments used by their APTs.

However, Kaspersky analysts ultimately analyzed the code and eliminated both China and North Korea from responsibility for this attack . However, the Russian security firm refused to name the GRU as responsible for such an attack. The group behind Olympic Destroyer is now commonly known in the security community as “Hades,” due to the Olympics’ Greek origins.

Hades, Sandworm, and FancyBear are all believed to be under the control of the same organization, the GRU. Each attack campaign has overlapping TTPs, helping experts attribute these attacks.

Attribution is one of the most difficult parts of malware analysis , but understanding a campaign’s origins helps us learn more about the threat. The GRU is the same organization responsible for other ruthless attacks, such as the downing of MH17 in Ukraine and the assassination attempt on Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom, although little is known about these National State units.

An interview with members of the think tank Chatham House described the political tension between the agencies as “like watching bulldogs fight under the rug,” though the details of this interview were not disclosed. Many of these elaborate cyberattacks on critical infrastructure are thought to be part of the GRU’s attempt to prove its usefulness and prevent it from being disbanded, like the KGB.

The current Geneva Convention prohibits targeting and killing civilians and medical personnel during wartime. However, cyberattacks on power grids and hospitals by national states during peacetime could cost lives.

It’s also worth noting that Sandworm came very close.

From analyzing SandWorm attacks, hackers always seem to hold back from causing irreversible damage to ICS and power grids, never revealing their full cyber arsenal . This is unlikely to have been out of compassion, but rather because Sandworm was saving its true capabilities for something more sinister to use in the future.

Speaking to U.S. cybersecurity consultants, Andy Greenberg (author of the book “Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwar and the Hunt for the Kremlin’s Most Dangerous Hackers” ) learned that the United States is unlikely to support a Geneva Convention on Cyberattacks. This is because the United States wants to wage cyberwarfare itself.

US officials admit that foreign governments are constantly probing each other and even infecting critical infrastructure with malware, but they never “pull the trigger.” It’s also worth noting that Sandworm has never gotten this far. Analyzing all the attacks, hackers always seem to hold off on causing irreversible damage to ICS products on power grids, never revealing their entire cyber arsenal.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.