How three insiders with just $200 in their pockets reached a market capitalization of $5 trillion and created the company that powers over 90% of artificial intelligence.

Kentucky, 1972. A nine-year-old Taiwanese boy who speaks little or no English arrives halfway around the world and discovers that his roommate is eight years older than him, covered in tattoos and scars. His parents in Asia thought they had sent him to a prestigious private boarding school. It was the Oneida Baptist Institute , a rehabilitation center for troubled kids.

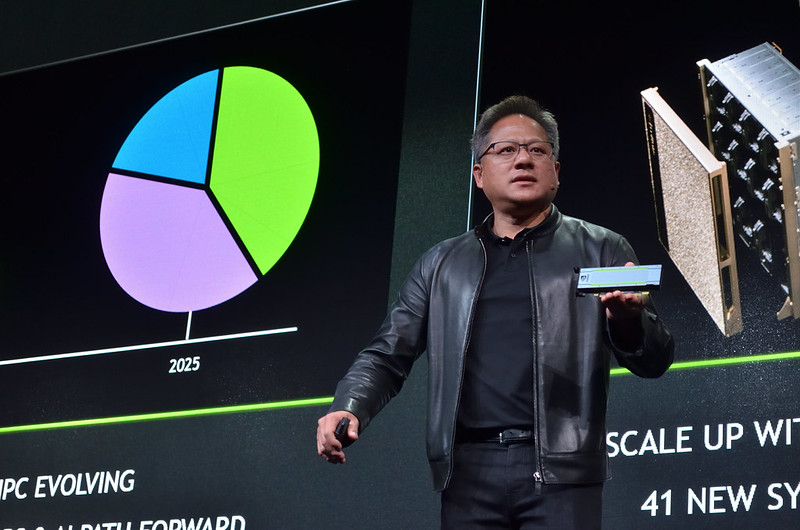

That kid is Jensen Huang . Today, he has a personal net worth of over $150 billion . His company, Nvidia , has a market capitalization of nearly $ 5 trillion. Its chips power over 90% of AI systems : ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Midjourney. Every model you use, every AI image you generate, every response you receive runs through an Nvidia processor.

And it all started with a mistake and $200 in your pocket .

Taiwan, 1963. Jensen Huang was born in Tainan to a middle-class Taiwanese family. His father worked as a chemical engineer for an oil company, and his mother taught elementary school. When he was five, the family was forced to move to Thailand for work. His mother held the reins of the family, also taking care of the children’s education, including English. But Thailand in those years was not a peaceful place. Tensions and political instability were the order of the day. For this reason, the Huangs made a radical decision.

At nine years old, Jensen and his older brother are sent halfway around the world to live with their uncle and aunt in Tacoma, Washington. He barely speaks English. His uncles, recent immigrants, have little knowledge of the American school system and enroll the boys in what they believe to be a prestigious private boarding school: the Oneida Baptist Institute in Kentucky. The reality? A rehabilitation center for troubled kids.

A tough place. Jensen finds himself rooming with a boy eight years older than him, covered in tattoos and stab scars. Jensen teaches him to read; in exchange, he convinces him to lift weights. He learns to earn respect. Meanwhile, his parents, who remained in Asia, sacrifice themselves to sell almost everything they own to pay the school fees. When they finally manage to join their children in the United States, the family reunites and settles in Beaverton, Oregon.

At fourteen, Jensen was a shy, introverted teenager. However, he had several talents, including: he studied obsessively and was a great table tennis player. In 1978 , at fifteen, he came in third in the junior doubles at the US Table Tennis Open . Not bad for a fifteen-year-old.

Among the many problems he faces is money. There’s none. That’s precisely why he has to start earning a living early. Very early. His first job? At Denny’s , the 24-hour fast food chain. He starts out washing dishes, then over time he climbs the kitchen ladder. From dishwasher to busboy, finally to full-fledged waiter. Portland, night shifts, drunk customers, the smell of grease. Years later, Jensen will say: that job was crucial, not just for the money, but for shaping his character.

While attending Aloha High School in Beaverton, he discovered computers. An Apple II, the BASIC language, the first video games on a terminal connected to a mainframe. Something clicked. It wasn’t just curiosity, it became an obsession.

After graduating high school, he enrolled in the electrical engineering program at Oregon State University. During his sophomore year, something important happens: he meets Lori Mills, who becomes his lab partner. Jensen is seventeen, the youngest in the class. She is nineteen. He tries a technique that is understatement, but clever: “Do you want to see my homework?” He promises her that if she studies with him every Sunday, she’ll get straight A’s. It works. So much so that after graduation, they get married.

In 1984 , after graduating, he began sending out resumes everywhere. Texas Instruments rejected him. AMD and LSI Logic responded: both wanted to hire him. He chose AMD as a microprocessor designer, but after about a year, he was already restless. He continued working, had two young children (Spencer and Madison), and in the meantime, enrolled at Stanford for a Master’s degree in Electronics. He earned his degree in 1992 , making great sacrifices and studying in the evenings and on weekends.

But it’s not enough for him. AMD pays him well, his family is growing, but he feels he needs to do something bigger. When he hears about the new chip design processes at LSI Logic, he doesn’t think twice—he leaves AMD. At his new company, LSI, he’s given an interesting project: to assist Sun Microsystems on the design of an accelerated graphics card. It’s the turning point. It’s here that, collaborating on a shared project, his path crosses that of Curtis Priem and Chris Malachowsky . They will become his future partners.

The three worked together for years, arguing like crazy because they had different personality profiles, but precisely because of this they produced good stuff. In 1989 they completed the GX graphics engine . It worked. And how it worked: Sun Microsystems’ revenue went from $262 million to $262 million. in 1987 to 656 million in 1990.

Jensen was promoted to director of CoreWare, a division of LSI Logic. But after 1990, Sun Microsystems slowed down. Despite working in different contexts, Jensen and Priem maintained excellent relationships with Sun’s management team. Jensen (then at LSI Logic) was called to review a highly confidential project: a branch office was working on the development of a new programming language, Java . Priem was asked to design a chip that would work alongside the CPU to accelerate the execution of the new language. The three of them—Jensen, Curtis, and Chris—began to question themselves. They had an idea. Why not do it themselves, start their own business? So they all quit their permanent jobs. They took the plunge.

Developed in the early 1990s, the introduction of the PCI bus made it easier to design high-performance cards. Windows 3.1, released in April 1992, introduced several new features, including a new font format (TrueType) and the ability to play videos in the newly developed AVI format. Given its features and millions of copies sold, Windows paved the way for innovative graphics.

Taking advantage of these innovations and their experience designing graphical user interfaces for Sun Microsystems, that same year, Curtis Priem and Chris Malachowsky began to sketch out a first business idea. The idea? To distribute a workstation flight simulator developed by Priem to the PC market, without having to build their own boards.

In 1992, the three future partners began seeing each other regularly. The meeting place was a Denny’s on the corner of Capitol and Berryessa, in east San Jose. They sat, ordered, and talked for hours. Jensen, more pragmatic, wanted numbers, not dreams. A minimum annual turnover of fifty million , otherwise no resignation. The other two stared at him: instinct was enough for them. But Jensen had a family: a wife, two children, a steady income. Why risk everything to follow two people who couldn’t wait to leave their jobs?

Eventually, the numbers worked out. But a domestic problem remained: Jensen’s wife, Lori, didn’t want her husband to make the first move. Malachowsky’s wife felt the same way. Neither of them could quit first. The situation was at a standstill.

It was Priem’s move that unlocked everything. On the last day of 1992, he handed in his letter of resignation. Twenty-four hours later, alone in his Fremont apartment, he declared that the company virtually existed. But no money, no employees, no name. Just an idea and a phone call to the other two: if you don’t follow me, I’ll fail on my own. It was pure emotional blackmail. But it worked. Malachowsky shut down the project he was working on; the GX chip needed to be finished, a matter of principle, and it was released in March. Jensen signed on February 17th . He was turning thirty.

Nvidia was born: composed of three partners, a company without a name, without capital, and without employees. But Priem and Jensen had clear ideas. They already knew what to devote all their resources to and already had their first project in mind: a graphics accelerator for the then-new PC market. They would call it NV1 (Next Version 1).

Their first office was provided by Priem, his apartment in Fremont, a suburb of San Jose, as their first base of operations. The enthusiasm of the three founders was contagious: several former colleagues decided to leave their safe positions to join the startup. Among them were Bruce McIntyre, former lead programmer of the GX group, and David Rosenthal, a processor architecture specialist who would become head of Research and Development.

Ten people crammed into an empty apartment, no pay, workstations propped up on makeshift tables. At this point, all that was missing was a name. The first idea was ” Primal Graphics “: the initials of Priem and Malachowsky stuck together. Too bad there were three founders. They tried adding Huang: it came out unpronounceable. Discarded.

Having eliminated the option of personal names, Priem began looking for alternatives. While researching the etymology of the English word “envy,” he came across the Latin “Invidia,” a reference to the feeling the success of the GX chip had aroused among the insiders. After a discussion among the partners, they decided to change Invidia to Nvidia, dropping the “I,” with the hope that one day the company would truly be the envy of others (a hope that was spot on).

For the articles of incorporation, Jensen turned to Cooley Godward, a firm specializing in technology startups. At the first meeting, the lawyer, while drafting the Articles of Association, got straight to the point: ” How much money do you have in your pocket now ?” Jensen dug into his wallet: two hundred dollars. “Good,” the lawyer ordered, ” pay it now: from now on, you are officially a shareholder of Nvidia .” The other two partners also contributed the same symbolic amount.

It was April 5, 1993 : Nvidia was officially born. That same day, Priem went to the DMV. He ordered a personalized license plate with the same name as the new company.

There were already dozens of graphics chip manufacturers on the market. The 3D gaming industry was in its infancy, and giants like Matrox and S3 produced almost exclusively 2D graphics chips. But Jensen saw the potential of video games and 3D graphics.

When Jensen had submitted his resignation at LSI Logic, the boss had sent him straight to the CEO. Wilfred Corrigan thought he could convince him to stay. Instead, as soon as he understood what the boy wanted to do, he asked if he could join the deal. Then he picked up the phone and called Don Valentine , the founder of Sequoia Capital, a venture capital fund that has financed Apple, Atari, Cisco, among many other companies. Oracle, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Google. All he told him was: trust me, this guy’s good.

The meeting with Valentine was a disaster. The three showed up with a prototype, convinced that simply demonstrating their capabilities was enough. But Valentine, an experienced financier, wanted more: the market, competition, margins. Priem launched into technical explanations that no one understood. Jensen tried to reconsider, but it was too late. They left convinced they had failed.

Valentine, however, had already made up his mind. Corrigan’s references carried more weight than a failed presentation. A few weeks later, the answer arrived: two million dollars, half from Sequoia and half from Sutter Hill. With a warning Jensen would never forget: “If you lose it, I’ll kill you.”

Jensen was asked to produce chips in-house, without outsourcing production, but he refused. Nvidia would only design the chips, while companies like TSMC would handle the manufacturing. This fabless production model would become the industry standard. Only three companies in the world had made that choice in 1993. Valentine invested, and Nvidia survived.

But another twist in the story came years later. In 2006, Nvidia launched CUDA , a platform that allowed GPUs to be used not just for graphics, but for general-purpose computations. At the time, it seemed like a strange move. GPUs were for gaming, right?

CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) was launched in 2006 in conjunction with the G80 architecture, the first GPU designed for general-purpose computing. The CUDA paradigm allowed complex problems to be broken down into thousands of parallel tasks, executed simultaneously on GPUs using the SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Thread) model: a single instruction executed by thousands of threads in parallel, each on different data.

Jensen saw further. He understood that parallel computing , the strength of GPUs, would become fundamental to fields that didn’t yet exist: machine learning. Deep learning. Artificial intelligence.

Confirmation came in 2012. Alex Krizhevsky used two Nvidia GPUs. GTX 580 to win the ImageNet Challenge, an image recognition competition. Its model, AlexNet , demolished the competition with a 15.3% error rate versus the runner-up’s 26% . It was the moment the industry realized: deep learning works, and it takes computing power. Lots of it.

At the time, Google was using 16,000 CPUs to train an AI to recognize a cat. With 12 Nvidia GPUs, it took a tenth of the time. Jensen was right, ten years ahead of his time.

Today, over 90% of AI models are trained on Nvidia GPUs. GPT-4, Gemini, Claude, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney all use the same infrastructure. AMD and Intel compete for the remaining share.

When OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November 2022, the world suddenly discovered what generative AI was. But behind that simple interface were thousands of Nvidia A100 GPUs, each costing tens of thousands of dollars, working in clusters to train and run the model.

Nvidia doesn’t just make chips. It makes the infrastructure that enables modern AI. And Jensen Huang, that boy who washed dishes at Denny’s, became the man who accelerated the future.

Thirty-two years after that day at Denny’s, Jensen Huang steps onstage wearing his iconic black leather jacket. He still wears it. But when asked why, he replies, “So I don’t have to waste time deciding what to wear. I have more important things to think about.”

This is the same boy who, at nine years old, shared a room with a troubled teenager. Who washed dishes to pay for his studies. Who convinced two colleagues to quit their permanent jobs for a crazy idea.

Today, its chips train over 90% of the world’s artificial intelligence . ChatGPT? Nvidia. Gemini? Nvidia. Claude, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion? All Nvidia.

From $200 to nearly $5 trillion in market capitalization in 32 years.

But the most incredible thing isn’t that. It’s that in 2012, when AI was still science fiction for most people, Huang had already figured it all out. He had seen the future ten years earlier. While everyone else was making video game chips, he was building, brick by brick, the infrastructure for a world that didn’t yet exist.

And today, while Jeff Bezos is the guest of honor at the Italian Tech Week in Turin and spoke about space datacenters powered by GPGPU and CUDA architectures, those same architectures that Nvidia invented, one wonders: what is Huang seeing now that we will see in ten years?

But there’s one detail that explains just how powerful Huang has become: the European paradox. While Europe invests billions in ” digital sovereignty ” to emancipate itself from the United States, it discovers that that same autonomy relies on Nvidia chips.

One example above all? The Bologna Technology Park. In 2022, Leonardo , one of the most powerful supercomputers in the world, was inaugurated. A €240 million investment, it is the flagship of the EuroHPC initiative for independent European artificial intelligence. The problem? Leonardo beats with a Californian heart: it runs on 14,000 Nvidia GPUs .

The same story goes for Leonardo SpA’s DaVinci-1 supercomputer or Germany’s Jupiter , the continent’s first “exascale” system. Europe can write the rules and control the data, but the hardware that trains the models and accelerates the future still comes from Jensen Huang.

Nvidia’s true power lies not only in its chips, but in the CUDA ecosystem it created in 2006: today, anyone serious about AI has no alternative. It’s a technological dependency that has become geopolitical: Huang hasn’t just built a company, he’s created an infrastructure the world can no longer do without.

Nvidia’s history shows that success in tech doesn’t happen by accident. It takes a long-term vision : Jensen invested in CUDA six years before anyone understood why. Believing in an idea when no one else does. It takes working at Denny’s at 3 in the morning, amid the smell of grease and night shifts, to build a future.

You have to risk everything: your stability, your salary, and that last $200 in your pocket for a dream. But above all, you have to see the future before it becomes visible to everyone else. Everything else is just consequence.

NVIDIA BIOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

EUROPEAN HPC AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE DATA

GEOPOLITICAL ANALYSIS AND COMPETITIVENESS

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.