This article analyzes the disclosure submitted to Microsoft and available in English on digitaldefense , where images, demonstration videos and a Python code example are available.

In recent years, digital communications security has amplified a certain paradigm: attacks no longer aim simply to violate the infrastructure, but to dismantle user trust by exploiting every type of cognitive hook.

If email, calendars, and collaboration platforms represent the center of gravity of corporate life, the most effective attack surface is not the purely technical one, but the one capable of impacting the human factor.

The phenomenon analyzed in this article certainly doesn’t concern marginal products or theoretical scenarios. It affects Outlook Web and Outlook Desktop in its modern version, as well as Microsoft Teams in both the Web and Desktop versions. We are therefore talking about the ecosystem on which the daily operations of many companies are based. In this context, an important note deserves to be made: the ” classic ” version of Outlook, the historic and older one, is not affected by the problem. The critical behavior emerges only in the new application stack, where the interface has assumed a more central and integrated role in the user experience.

In this context, the findings reported later in the article, relating to a communications environment based on Microsoft Outlook and Teams, take on critical importance. Understanding them means gaining awareness of what can happen in a company’s day-to-day operations.

We’ll show how it’s possible, with relative ease, to manipulate the interface, alter the sender’s identity, and direct the user to destinations controlled by the attacker. All this by exploiting the established trust in the productivity tools we use every day, dramatically increasing the likelihood of success for malicious campaigns.

This is a prime example of how even the most common tools, if not supported by an adequate security model, can become insidious and unexpected risk vectors.

Making the issue even more relevant is the context of the disclosure. The vulnerabilities were first reported to Microsoft MSRC in December 2024 (VULN-144184). Despite the obvious impact on user trust and the interface’s ability to deceive, the behavior was classified as ” expected ” or not worthy of a corrective action.

The report was reopened in October 2025 (VULN-164593), with a broader set of technical evidence, complete evidence of the entire attack chain, and the introduction of two additional vulnerabilities capable of altering the behavior of the tools. These new vulnerabilities were also classified as ” moderate ,” with no estimated remediation date (ETA), while the two impersonation vulnerabilities, which allow an attacker to be presented as a legitimate insider, were considered expected behavior.

Further complicating the situation is the decision not to associate any CVEs. The official reason is that no user intervention is required and that any mitigations can be applied silently on the SaaS side. This approach eliminates the possibility of transparently identifying vulnerabilities and prevents credit from being given to those who discovered them. Consequently, the chain of trust between researchers and vendors is weakened, discouraging responsible disclosure and normalizing the risk for end users.

This framework raises an uncomfortable question for the industry: If a vulnerability doesn’t compromise the systems of the company that develops them, but undermines the trust of the users who use them every day, can it really be treated as a minor issue?

Traditional phishing campaigns attempt to convince users to open an attachment or click a suspicious link. Today, the stakes are raised: suspicion may not be enough. The attacker can impersonate internal identities and present themselves through credible visual cues: name, profile photo, company background.

The key is the management of ICS (iCal) files, which Microsoft uses for calendar requests. This involves normally legitimate ical fields, such as:

The attacker does not use an exploit, but standard features, manipulating them to his advantage.

Result:

This dynamic brings about a qualitative leap: the user no longer sees a suspicious link, but rather a reliable platform function.

The value of a modern interface lies in its ability to abstract away complexity. But where the interface simplifies, it creates security blind spots.

When a user sees an invitation in the calendar:

the level of mistrust reaches almost zero.

There is no longer any suspicious context, there is no external domain in the body of the email, there is no warning banner.

The attack exploits deep-seated trust in the Microsoft 365 ecosystem, not an isolated technical flaw.

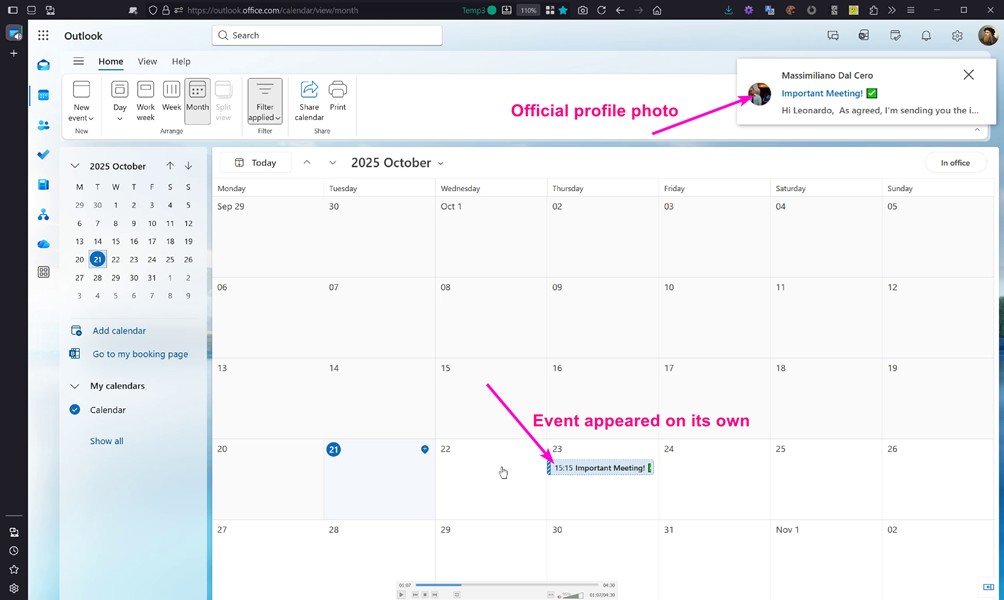

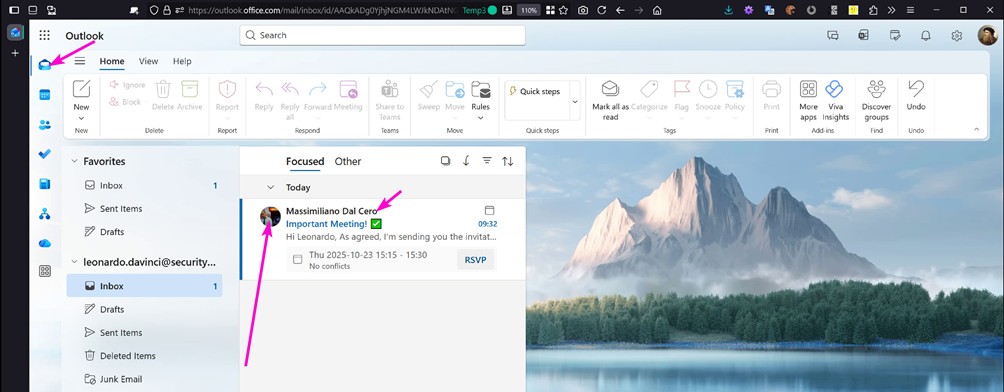

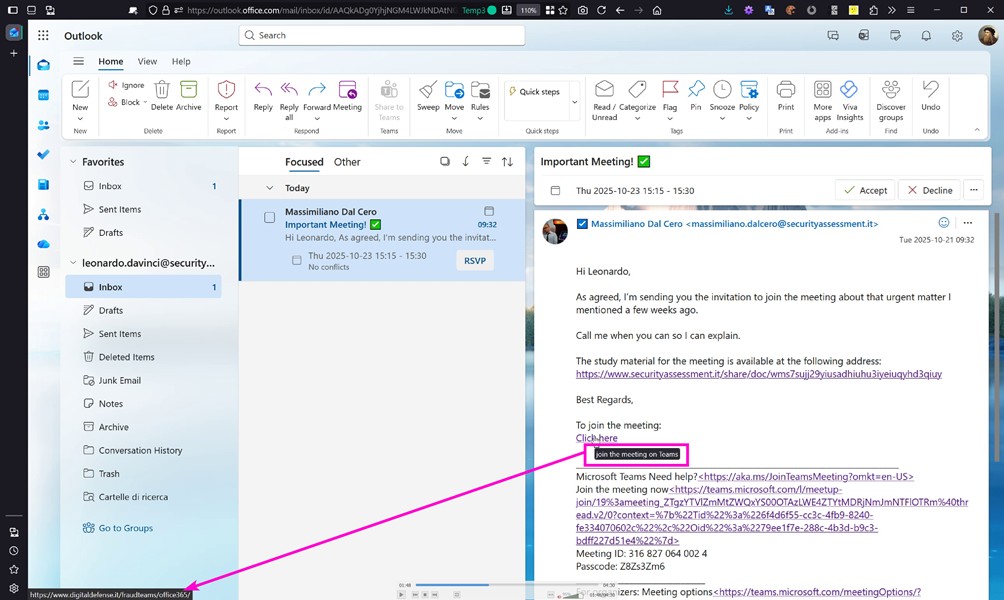

In the observed cases, a further element emerges that amplifies the risk: the disappearance of the wording “on behalf of” from received emails, achieved with a simple technical trick, such as inserting a long sequence of “_” (underscores) in the sender’s name. The user is faced with an email that appears to come from an internal ( or even external ) account, complete with all the graphic elements associated with that contact that the interface would normally display, such as profile photos and related information. Not because these elements have been altered or artificially generated, but because the applications involved actually extract and display the impersonated contact’s data. This occurs even if the email was sent via SMTP from a third-party service, such as Gmail, without the essential need to register fake domains to mislead the user.

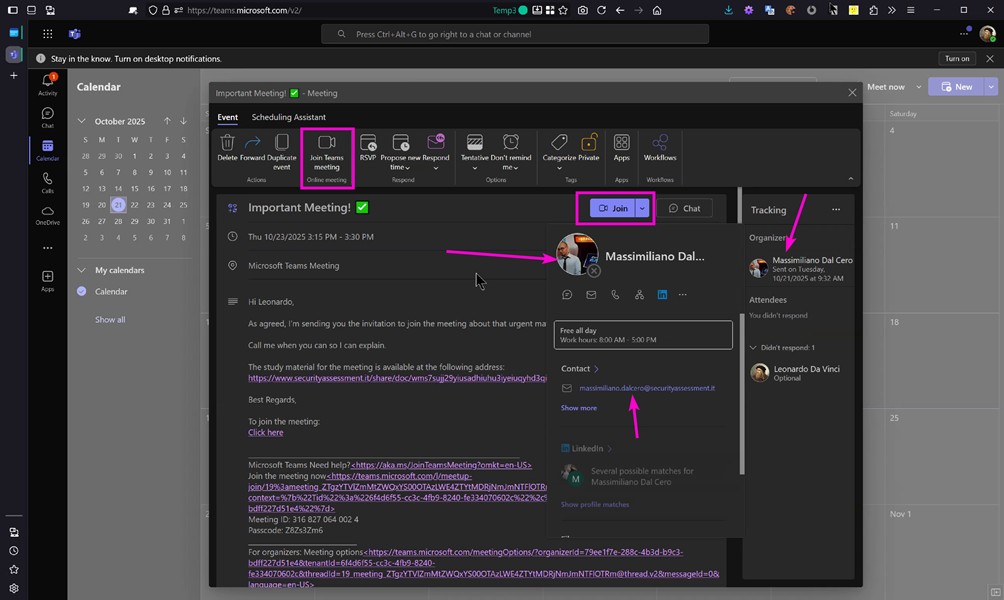

The critical point arises when the content of the invitation is automatically projected into the calendar : the email, though altered, still retains traces of its external origin, while the scheduled event loses them completely . References to third-party services disappear from the calendar, as does any indication of the real sender, leaving only a “clean” representation of the impersonated identity, with the relevant name and company profile photo. The invitation is no longer a suspicious communication, but a seemingly internal appointment, coherent and perfectly integrated into the work context.

Email is the entry point, and the user is therefore faced with a message that appears to come from an internal account, complete with all the graphic elements associated with that contact, such as profile photos and related information. This isn’t because these elements have been altered or forced, but because the applications involved actually display the impersonated contact’s data. This occurs even if the email was sent via SMTP from a third-party service, such as Gmail.

It’s true that by looking at message headers or exploring less obvious corners of the interface, you can spot clues to the real origin. But the question is as simple as it is uncomfortable: how many users will actually do this? In visual perception and everyday use, the only identity that remains is the impersonated one, while the real sender disappears.

This isn’t a technical vulnerability in the traditional sense, but a flaw in presentation that undermines the trust model. The visible identity doesn’t match the real identity, creating an environment where the interface becomes part of the deception.

Automatically inserting calendar invitations opens up another vector: calendar flooding.

An attacker can saturate the corporate agenda with fraudulent events:

Why is it critical?

Risk scales linearly with the number of targets, not with the complexity of the attack.

The most insidious aspect, therefore, isn’t just the manipulation of the email message. An email arrives, and an invitation immediately appears in the user’s calendar, without any action being required. The email content may contain alterations, suspicious indicators, or traces of its true origin. The scheduled event, however, does not. It’s the “clean” version, devoid of any reference to third parties.

Once the invitation is inserted as a calendar event in Outlook or Teams, the system completely loses all reference to the address or external service that generated it. Only the visual representation of the impersonated account remains: name, profile photo, and apparent identity of the organizer. Anything that might suggest an illegitimate origin is absorbed by the interface.

Email is the entry vector, the calendar event is the Trojan horse. The user, or even worse, a corporate group using the calendar as an operational source, no longer sees just a suspicious message or an anomalous sender. They see an internal appointment, formally consistent with the corporate context and accompanied by the UI they’ve learned to consider “secure.”

We’re not talking about a cosmetic flaw, but a short circuit in the trust model. We go from a communication that still carries traces of its real origin to an application object that no longer retains any. The attacker stops appearing like an attacker. They become a colleague, a manager, a contact, a trusted contact. And at that point, the user simply stops defending themselves.

The most sensitive issue isn’t unique to Microsoft. It’s an industry-wide problem.

Interface security isn’t treated like system vulnerabilities because it doesn’t cause RCE, privilege escalation, or memory corruption. It doesn’t “break” servers.

But security is not just technical integrity.

A platform that leads millions of people to automatically click buttons whose meaning can be altered is a vulnerable platform, even if the backend is intact. This would be like saying that an XSS isn’t a vulnerability just because it doesn’t affect the backend.

Companies operating today in Microsoft 365 ecosystems are no longer subjected to technical attacks, but rather to attacks that attempt to undermine their trust. Therefore, security must also be an integral part of the user interface, which is essentially what the majority of users encounter on a daily basis.

If a vulnerability exposes “only” users and not the platform, should it be considered “moderate”? In a world (still) made by humans, the answer is simple: no!

When the privileged perimeter is human behavior, it is not enough to say that the problem does not affect the infrastructure or systems.

An attack that blurs the lines between legitimate and fake interactions is a key issue, as it undermines the very principle of authenticity.

In a context where:

Trust in the interface is a primary security asset.

And it must be treated as such.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.