MS13-089 opens a leak site on the dark web, exposes the first data and adopts a double extortion strategy without encryption.

For years, “MS13-089” identified a 2013 Microsoft security bulletin addressing a critical vulnerability in the Windows GDI graphics component that could be exploited for remote code execution. Today, the same acronym is being recycled as the name of a new ransomware group, MS13-089.

This choice isn’t just a whim: reusing a historic Microsoft identifier introduces noise into OSINT research and shifts attention from the “street gang” imaginary to the “software vulnerability” one . In practice, the group immediately places itself within the cyber perimeter, exploiting an acronym that analysts have been associating for years with a well-documented security problem.

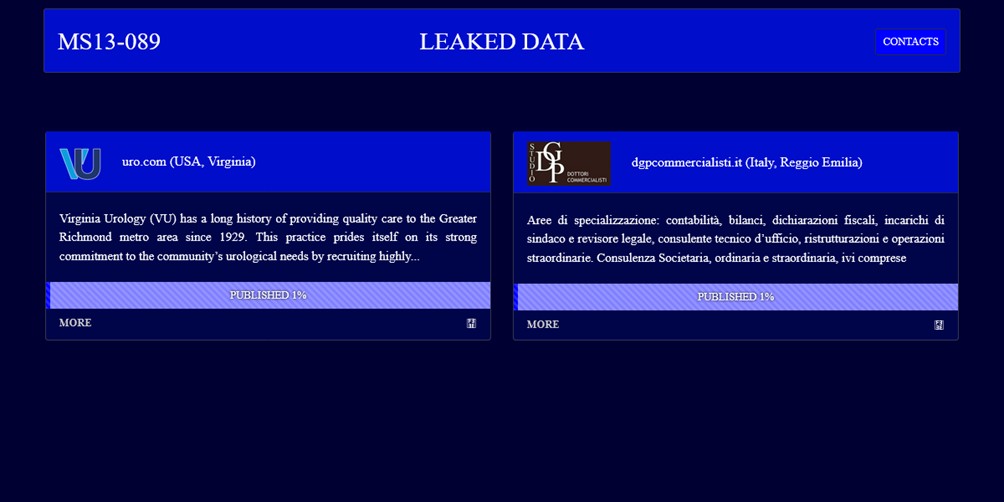

The screenshot, shared by several websites and social media channels on the leak site’s clearnet, shows a basic layout: the name MS13-089 at the top, the “LEAKED DATA” section in the center, and immediately below it two side-by-side cards dedicated to the first victims. Each box features the logo, domain, a short official description from the victim’s website, and a bar with the words “PUBLISHED 1%,” along with a “MORE” button.

This structure follows the now standard model of double-extortion leak sites: a prominently displayed gang brand, a list of targeted organizations with a summary profile, and a clear invitation—a “MORE” button—to explore the published data samples as evidence of the intrusion.

The “PUBLISHED 1%” bar appearing under each victim isn’t a visual gimmick, but rather an indicator of the level of public exposure of the data. In ransomware leak site jargon, this label signals that only about 1% of the stolen data has been made public , while the remaining 99% is still being held by the group as leverage in negotiating with the victim.

One of the most distinctive aspects of MS13-089 is its declared decision not to encrypt victims’ systems , focusing exclusively on theft and the threat of data leaks. In communications reported by breach monitoring sites, the group claims to have not encrypted Virginia Urology’s assets “to avoid harming patients,” claiming a strategy based solely on double extortion.

This narrative—already seen in other contexts where actors attempt to present themselves as “professionals” rather than vandals—doesn’t change the substance: the exfiltration of medical records, insurance data, and tax documentation remains a serious threat, with potential repercussions for millions of people and significant regulatory implications (HIPAA in the US, GDPR in Europe). The lever is no longer operational paralysis through encryption, but the threat of irreversible public exposure.

The debut of MS13-089 confirms key trends in the ransomware landscape:

For defenders, this means integrating response playbooks not only for mass encryption scenarios, but also for cases where the entire impact is on the data leak: constant monitoring of leak sites, the ability to react quickly to partial disclosures, and communication and notification plans designed to manage the progression from “1% disclosed” to the threat of full exposure.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.