Password security and human behavior are more connected than we think.

In previous episodes, we tried to shift our focus: passwords don’t just protect systems, they tell stories about people.

The choices we make when we enter a login box speak of memory, haste, habit, and trust. They speak of us, even before they speak of technology.

Now let’s take it a step further.

We no longer look only at what we choose, but what happens when a system asks us something: to stop, to remember, to change, to pay attention.

That’s when security stops being invisible.

And it’s starting to make itself felt.

There’s a fundamental misunderstanding that’s plagued the way we talk about digital security for years: the idea that if a system slows down, stops, or demands attention, then it’s poorly designed. It’s a convenient illusion, but an illusion nonetheless.

Security makes noise.

And that noise has a precise name: annoyance.

In the physical world, we’ve learned to accept it without much discussion. Seatbelts constrict, helmets weigh and ruffle hair, security checks slow us down, turnstiles block our passage. None of these elements are designed to be pleasant: they’re designed to function.

We tolerate them because we understand their purpose. We know that this discomfort isn’t gratuitous, but serves to reduce risk, to limit harm. In the real world, discomfort is a signal we’ve learned to interpret.

In digital, however, we demand the opposite. We want frictionless protection, seamless security, and controls that go unnoticed. But security that isn’t felt is rarely recognized as such.

The point that’s often overlooked is this: the security disruption doesn’t just penalize those who use the system. It especially penalizes those who attack it.

An extra step, an expired code, or an unexpected verification only slightly slow down a legitimate user. For an attacker who needs to automate, scale, and repeat the action multiple times, that same slowdown becomes a serious obstacle.

The attack thrives on speed, continuity and repetition.

The annoyance breaks all three.

When someone complains about having to change a password or pause for an update, they’re not reporting a bug. They’re signaling a misunderstanding of the bug’s purpose. They’re reacting like someone who wishes for a seatbelt that doesn’t constrict or a helmet that doesn’t weigh them down.

Safety isn’t meant to be invisible. It serves to interrupt automaticity, create a moment of attention, remind us that what we’re doing has value and risk.

If it doesn’t slow down, if it doesn’t disturb, if it doesn’t make itself noticed, if it doesn’t make noise, it isn’t protecting anything.

And if this noise bothers us, the problem is not the noise itself.

But having forgotten why it exists.

Someone, at this point, will object:

“But today we have biometric authentication, transparent encryption, silent updates… why should we still put up with all this hassle?”

The answer is simple.

When those technologies actually work, cover the entire perimeter, and have no known flaws, the nuisance can—and should—go away.

The problem is that, in the vast majority of Italian realities in 2025, we are still far from that paradigm.

As long as we remain in this imperfect world, expecting serious protection without any friction is like expecting an airbag that doesn’t make a noise when it deploys.

If it doesn’t make any noise, it’s probably not there. Or it’s just not working.

But how does this “noise” translate into a concrete choice in the password world?

The answer lies in a concept that combines psychology and mathematics: password entropy.

In information theory, starting with the work of Claude Shannon (1948) , entropy measures the uncertainty of the probability distribution from which a password has been extracted.

To put it simply, but without betraying the theoretical meaning , in practice, when choices follow predictable human patterns—as they almost always do—that uncertainty collapses, and guessing becomes much easier. This is why, in everyday language, entropy and predictability end up coinciding.

Passwords like Ciao123 , Marco1984 , Luna2020 , or Password! have extremely low entropy. Not because they’re naive, but because they’re predictable. They’re exactly the kind of strings that automated scripts try first, because they fit the most common patterns of human behavior.

A high-entropy password doesn’t have to be incomprehensible. It just has to be improbable to an attacker. And this is where one of the most common misconceptions arises: entropy doesn’t equate to chaos. A seemingly infernal sequence like fY9!gP0$BvTqZ isn’t synonymous with real security, but often a different problem. It’s the kind of password that ends up written on a piece of paper or improperly saved, turning into a vulnerability disguised as complexity.

Entropy increases as length and character variety increase, and, above all, as predictability decreases. Avoiding obvious connections to one’s personal life—names, dates, places, emotional references—helps.

But be careful: the absence of personal references does not automatically mean high entropy .

Tr0ub4dor&3 – a dictionary word disguised as leet speak – sounds creative, but it is one of the most common transformations: low entropy.

correct-horse-battery-staple doesn’t tell you anything personal, but it’s the most cited example ever: today it’s in the dictionaries of attackers.

dog-cat-table-17 has no obvious connections, but follows a very banal pattern (noun–noun–noun–number): mediocre entropy.

The decisive factor, therefore, is not the absence of personal references per se, but the absence of recognizable patterns .

Entropy actually increases when the password escapes the patterns that attackers already know and exploit. It may not reveal anything about the user, but if it’s constructed following a predictable structure—dictionary words with some numbers, leet speak, keyboard sequences—uncertainty remains low.

The goal is not to make life difficult for those who use it, but to make it difficult for those who try to guess it.

It’s worth pausing for a moment here and looking at the math, because it’s much simpler than it seems.

And above all because, translated well, it says something banal: the more possibilities there are, the more unlikely it becomes to guess “by trial and error” .

The number of possible passwords grows as follows:

N = A^L

where A is the number of possible characters (letters, numbers, symbols) and L is the length of the password.

If an attacker tries R guesses per second, the average time needed to guess it is:

T ≈ A^L / (2 R)

This is the ideal estimate, assuming the password is truly random. In reality, when we follow predictable human patterns, the effective time for an attacker is much lower.

But the exact number is not the point.

The point is the order of magnitude.

Each additional character doesn’t add effort, it multiplies it . We’re not talking about “a little longer”: we’re talking about a leap in scale. It’s the difference between trying a few doors and finding yourself faced with an entire neighborhood of identical doors.

Two more characters means A² times more attempts. With common alphabets, we’re talking thousands of times more work.

In realistic scenarios, this means going from days to decades, from decades to times that easily exceed a human lifetime.

If it seems exaggerated, we can always do as the distrustful professionals do: take the formula, do the math and try to disprove it.

Mathematics doesn’t give discounts, but at least it’s consistent.

For years, we’ve heard the same old story: complex passwords, mandatory symbols, forced changes every few months. Noisy security, yes—but often in the wrong way.

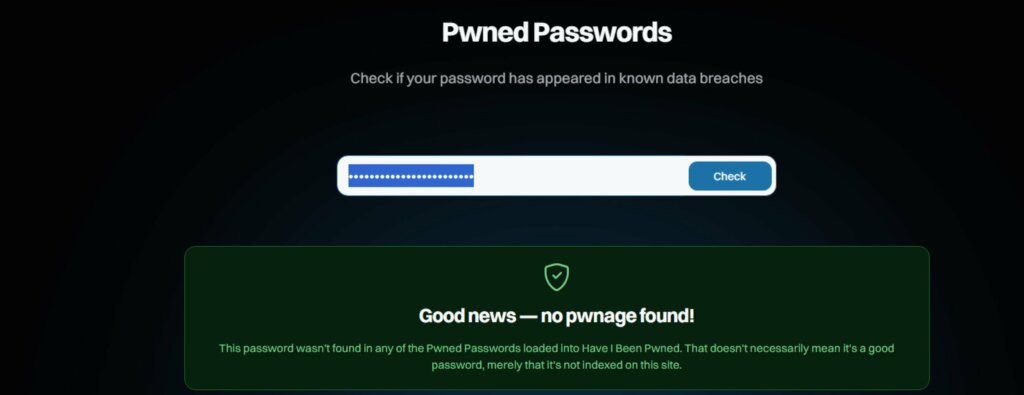

In recent years, however, even official guidelines have changed direction. The most recent recommendations from NIST , the international reference body for digital identity, have called into question precisely those practices that seemed untouchable.

The bottom line is simple: length matters more than complexity .

For years, forcing symbols, capitalization, and artificial rules has produced a notorious side effect: passwords written on post-it notes, repetitive patterns, and minimal, predictable variations. More problems, not more security.

The new orientation is different:

In other words, less ritual and more substance.

Less unnecessary noise, more friction where it really matters.

This is an important paradigm shift, because it finally acknowledges an uncomfortable truth: security that ignores human behavior ends up circumventing it .

And this is where passphrases come into play.

A passphrase is simply a phrase transformed into a password. And it’s one of the few solutions that increase entropy without waging war on human memory. It’s long, natural, difficult to predict, and surprisingly easy to remember.

Even in this case, however, not all phrases work. The obvious ones— horse.coffee.snow.Thursday , sunsethappensat6pm , apuppyisnotapassword —seem clever only to the person writing them. In reality, they are constructed according to common, recognizable logic, and end up exactly where all good intentions end: in the attackers’ dictionaries.

The trick isn’t the sentence itself, but the angle. Oblique memories work, not obvious ones. The ones that don’t reveal who you are, but that only you recognize. Then all you need to do is apply a simple, repeatable rule: initials, a symbol, a consistent style. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel every time: you need a method. And a consistent variation for every story.

For example, a personal sentence can become LmC_3vS! without being readable by anyone except the person who created it.

Not everyone uses a password manager, and it’s a common choice. There are human approaches that work because they respect the limitations of memory: systematically broken sentences, impossible geographical paths, juxtapositions of incompatible objects. Sequences like Paris→Lima→CardboardLake or LilacSpoon_DryCircle say nothing about you, but they stick in your memory. No attacker builds dictionaries of the absurd, while human memory manages them effortlessly.

A good password should also provoke a micro-emotional reaction. A half-smile, a feeling of strange familiarity. That’s enough to remember it. Better funny than biographical. Better strange than predictable.

There’s one rule, however, that doesn’t allow for exceptions: don’t use the same password for everything. It’s like having the same key for your house, car, office, and basement. And then leaving it at the bar.

Changing your password is annoying, there’s no denying it. But it’s much less annoying than losing an account, an identity, or a piece of work. A decent password shouldn’t reveal your life story, shouldn’t make you feel ashamed, shouldn’t force you to use a post-it note, and should never seem like it was created in a moment of panic.

It just has to work.

And leave us a minimum of dignity.

Continues…

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.