“Now that the genie is out of the bottle, it’s impossible to put it back!”. How many times have we written these words about artificial intelligence?

Now that the genie is out, as in the tales of the One Thousand and One Nights, we can’t pretend that nothing has changed. AI-based technologies are changing us rapidly – and profoundly – in every aspect of our lives. We write with AI, we speak with AI, we draw with AI, we write music with AI, and we still program, learn, and even think with AI.

But are we really ready?

Looking back, from Alan Turing to John von Neumann, from Marvin Minsky to John McCarthy – the man who coined the term “artificial intelligence” in 1956 and who participated in the Tech Model Railroad Club at MIT in Boston, where the hacker culture was born – we have come a long way. But despite their brilliant intuitions, these pioneers could hardly have imagined that one day, in the pockets of billions of people, there would be intelligent assistants capable of conversing, writing code, composing music, and generating images in a matter of moments.

And yet, as astonishing as the progress is, the greatest risk we face today is not the extinction of humanity at the hands of a superintelligence, as cyberpunk culture with Skynet and Terminator reminds us. The thing is much more subtle. It is the progressive loss of our ability to think. To reason. To connect, imagine, and critically evaluate.

They call it “mental decay”. And it is the shadow that looms behind every promise of artificial intelligence.

To control intelligent computers, we need humans who are even more intelligent than computers, but artificial intelligence only pushes us to download the information and let computers do the thinking for us.

This is the reflection –increasingly shared by scholars, educators, and philosophers– that should make us reflect. As Yuval Noah Harari, author of Homo Deus also observes, if people start delegating their decisions to intelligent agents, they will progressively lose the ability to decide.

The crucial point is this: everything is becoming too easy.

Writing an essay? There’s AI. Conducting a market analysis? There’s AI. Summarizing a book, planning a trip, interpreting a difficult text, designing a business strategy? There’s always AI. And this is progressively weakening our “cognitive muscle.” And it’s all directly proportional: the easier it gets, the lazier we become.

In fact, many people are starting to practice what the Anglo-Saxons call raw-dogging with artificial intelligence, to describe the direct and unfiltered relationship that some users are starting to have with AI. This confirms the Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University study, which found that greater reliance on AI tools at work was linked to reduced critical thinking skills. Furthermore, a study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) also analyzed what happens in our brain with intensive use of ChatGPT, correlating it with cognitive deficit.

Yes, many studies are coming out and they all agree in the same direction.

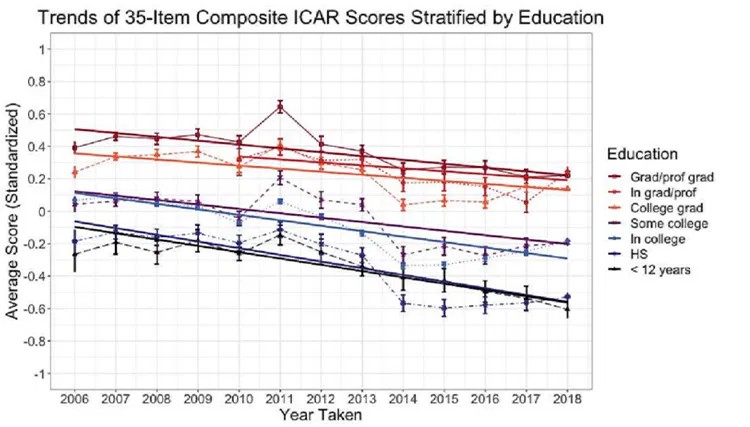

But to tell the truth, the path had already been traced. Since 1973, signs of a progressive reduction in IQ have been observed, a phenomenon that some scholars link to the massive introduction of television into homes. What for decades has been a positive trend in industrialized countries — known as the Flynn effect — is now showing a dangerous reversal of the trend that scholars call the “reverse Flynn effect”.

Recent decreases are attributed to environmental factors, increasingly “simplified” educational systems, massive use of digital media, a decline in deep reading, and cognitive delegation to external tools.

And AI is the icing on the cake in all of this.

But beyond the risk of mental decline, the impact of artificial intelligence is much broader: it affects numerous areas and concerns the entire society. This is because:

Artificial intelligence is not neutral!

It is a powerful tool in the hands of a few. Today, the most advanced models are controlled by a handful of big global players: Microsoft (with OpenAI), Google (with Gemini), Apple (with its new Siri agents), Amazon, Meta. And we must not delude ourselves: their mandate is not to improve the human condition or world hunger, it is always and only one: to generate profit. This causes the economy to become “polarized,” where few benefit from the replacement of human labor with AI, and many suffer its effects. Furthermore, their computational resources, their data centers, and their ability to access huge amounts of data are not replicable by ordinary mortals, much less by the poorest states.

For example, the report “The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines” published in 2020 by the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future clearly highlights howdespite productivity growth, the fruits of automation and AI are distributed in a highly unbalanced way.

This means that AI risks widening the gap that already exists between rich and poor, between the global North and South, between those who have access to tools and those who are excluded. According to a 2024 analysis by the World Economic Forum, 80% of the benefits of intelligent automation are concentrated in G7 countries, while in Africa and Latin America we are seeing a growth in automation without a corresponding growth in digital skills. An abyss that risks becoming unbridgeable.

And in this abyss lies the real threat: that artificial intelligence is not only an accelerator of economic inequalities, but also cultural and existential ones. Because those who own the algorithms also possess the ability to guide thoughts, consumption, and behaviors. And while the luckiest ones will be able to “rent” artificial intelligence to enhance their minds, billions of people risk becoming merely passive users of a system designed elsewhere, incapable of participating, understanding, and even choosing.

This is where technology, from a tool to free man, risks definitively transforming into an invisible and insurmountable cage managed entirely by machines.

In the next decade, AI will no longer simply answer our questions or generate content on demand: it will become both ubiquitous and invisible in our lives. Each individual will have a personalized AI assistant, who will manage everything from daily planning to mental health,

Artificial intelligence systems will evolve to know every detail about us, anticipating desires and fears, adapting news, entertainment, and social relationships in real time to maximize our attention.

We will live surrounded by digital assistants so refined that they seem like real people, capable of accompanying us in every daily choice, to the point of influencing what we dream of becoming.

In parallel, our very minds risk changing. With the habit of delegating creative, analytical, and decision-making processes, we will witness a silent but profound transformation, as seen in the previous chapter, “we think less and less with our own heads.”

We will therefore be a humanity increasingly accustomed to immediate answers and less and less trained in complexity. Critical thinking and the ability to sustain doubt may seem superfluous, replaced by algorithms that simplify every question. Memory will become external, stored on servers, while imagination will be shared and shaped by neural networks that think faster than us.

At the same time, technological inequality could generate new social fractures. Those who have access to the most advanced tools will be able to amplify their talent and influence, while a large part of the population will risk remaining spectators, unable to understand or control the logic that governs the digital world, even if forced by future “Digital Walls“. Democracies will have to face the challenge of increasingly powerful platforms, capable of influencing consensus and fueling “polarizations” never seen before.

The difference between those who control AI and those who suffer its effects could become the new dividing line between power and impotence.

And probably, after having gone so far and having realized that man risks becoming a servant of machines, some states will understand that it is necessary to reverse course. The idea of educating new generations by rediscovering teaching methods from the early 1900s could arise, even if this is just an example. One could hypothesize the creation of “pockets” of de-digitalization. I talked about it in the 2020 article introducing the concept of de-digitalization. And this way of acting would allow us to eliminate out-of-control AI agents, mass surveillance, technological dependence and influence by disconnecting from the internet and creating independent networks supervised by states or federations of states that support de-digitalization policies.

In short, Runet, Great Firewall of China, duties, rare earths, are just part of a path that will lead the world to erect these “walls”, to create an isolated cyber space, where the times of collaboration between peoples will be forgotten because the world’s dominance is technological and no longer human.

If we can imagine a technology that does not replace humans, but enhances them, we could enter an era where artificial intelligence becomes an ally of creativity and shared knowledge. We could create digital ecosystems that protect privacy, foster inclusion, and give back time to think, experiment, and make mistakes.

But humans don’t think like this. Always think of its own interest.

When machines become so good that we confuse (and it will happen soon) statistics and the soul, the discussion will be whether or not they have rights or not. The topic at that moment will be to ask ourselves: what is the soul? Can it be represented by a silicon body moved by pure statistics? And we will see some great things there.

Once upon a time, the great challenges were purely technological: creating the first computer, sending a man to the moon, building ever more powerful networks. Today, however, the real challenge no longer concerns just technology, but man himself. In an era in which machines are starting to “think”, designing more advanced systems becomes secondary to a much deeper question: how to protect what makes us human.

It is no coincidence that we are already starting to talk about a “human” language to communicate with these artificial intelligences (almost AGI, assuming anyone knows what this term means), which are nevertheless increasingly pervasive. At London Technology Week in June, someone jokingly said that “the new programming language of the future should be called Human!” . A joke, certainly, but one that perfectly captures the historical moment we are living in: machines are forcing us to interact with them using natural language, our own language, no longer to dominate technology, but to be able to dialogue with it without losing ourselves.

In this scenario, psychology and technology are merging. A few years ago, we were talking about ethics and gender differences. These are problems that have unfortunately already been forgotten and overcome. Now we have moved on to more serious matters and studies are multiplying to understand how human beings can adapt to a digital world dominated by intelligent assistants, robots, chatbots and predictive systems, without sacrificing memory, critical thinking and creativity. It is a delicate balance, in which what is at stake is not just efficiency or productivity, but our very ability to reason and think for ourselves.

Meanwhile, politics finds itself suspended between the interests of big tech – which today count as much as entire national economies – and the inability to truly read the long-term dangers. By doing so, we risk opening the doors to a widespread diffusion of digital agents, which, on the one hand, simplify our lives, but on the other, slowly erode the cognitive abilities of the youngest.

A slow slide towards a world in which we will no longer be masters of our choices, but simple executors of what machines suggest to us. And they will do it so well that we will trust them completely.

And yet, precisely in the awareness of this risk lies a seed of hope. Because if the great challenge is “human,” then only man can overcome it: by rediscovering his slowness, critical thinking, and creativity as indispensable values. We may not be able to stop technological progress, but we can still choose not to be its slaves and write the words “AI Free” in our songs, our articles, our source code, to signify that everything produced is the exclusive fruit of the human mind. Will we be on the market? Probably not, but it will be an important signal for many.

It is up to us to decide whether to live in a world governed by machines or in a world where machines remain, however, at the service of man. The question is no longer whether artificial intelligence will change the world. It is already doing so.

The real question is: will we be able to remain human, in the deepest and most authentic sense of the term, in a world dominated by thinking machines?

It would be nice to think of a future where AI becomes the microscope and telescope of the human mind, helping us explore even bigger questions that have remained unanswered until now. But unfortunately, this dream is still on the back burner.

Now the challenge is no longer technological. It’s cultural, educational, and above all political.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.