Edited by Luca Stivali and Olivia Terragni.

On September 11, 2025, what can be defined as the largest leak ever suffered by the Great Firewall of China (GFW) exploded in the media, massively and massively, revealing without filters the technological infrastructure that fuels censorship and digital surveillance in China.

Over 600 gigabytes of internal material have been put online – via the Enlace Hacktivista group platform: code repositories, operational logs, technical documentation and correspondence between development teams. Material that offers a rare window into the inner workings of the world’s most sophisticated network control system.

Researchers Journalists worked on these files for a year to analyze and verify the information before publishing it: the analyzed metadata in fact reports the year 2023. The accurate reconstruction of the leak was then published in 2025 and mainly concerns Geedge Networks, a company that has collaborated with the Chinese authorities for years (and which includes among its advisors the “father of GFW” Fang Binxing), and the MESA Lab (Massive Effective Stream Analysis) of the Institute of Information Engineering, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. These are two key pieces in that hybrid supply chain – academic, state and industrial – which has transformed censorship from a national project to a scalable technological product.

If the ideological veneer is removed, what emerges from the leak is not a simple collection of rules, but a complete product: an integrated modular system, designed to be operational within telco data centers and replicable abroad.

The heart is the Tiangou Secure Gateway (TSG), which is not a simple appliance, but a network traffic inspection and control platform, which performs Deep Packet Inspection (DPI), classifies protocols and applications in real time, blocks code, and manipulates traffic. We are not deducing this by clue: the documents “TSG Solution Review Description-20230208.docx” and “TSG-问题.docx” explicitly appear in the dump, along with the RPM packaging server archive (mirror/repo.tar, ~500 GB), a sign of an industrial build and release pipeline.

The TSG component is designed to operate on the network perimeter (or at ISP nodes), handling large volumes of traffic. The “product” perspective is confirmed by the vendor’s documentation and marketing materials: TSG is presented as a “full-featured” solution with deep packet inspection and content classification—exactly what the leak reports suggest.

The platform does more than just “keep out.” Some reports, summarized in the Chinese-language technical dossier, explicitly mention code injection into HTTP, HTTPS, TLS, and QUIC sessions. There is even the ability to launch targeted DDoS as an extension of the censorship line. This establishes the convergence between censorship and offensive tools, with a single control room.

From the summaries of the documents, we can reconstruct the functions of real-time monitoring, location tracking (association with cells/network identifiers), access history, profiling and selective blackouts by area or by event. These are not just slides: they are consistently cited capabilities that emerge from the content analysis of the leak of the Jira/Confluence/GitLab platforms, used for support, documentation and development of the TGS.

Above the network engine there is a “human” level: dashboard and network intelligence tools, which provide visibility to non-developer operators: these tools allow: search, drill-down by user/area/service, alerts, reporting and rule activation. Geedge itself advertises such a product as a unified interface for visibility and operational decision-making, consistent with what emerges in the leak on the control and orchestration part.

The fact that half a terabyte of the dump is a mirror of RPM packages says a lot: there is a build, versioning and rollout supply chain packaged for massive installations, both at the provincial level in China and via simple copies (copy-paste) abroad.

The leak confirms what several researchers have long suspected: China is not limited to using the Great Firewall (GFW) for internal control, but is actively exporting it to other regimes. Internal documents and contracts show deployments in Myanmar, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, and at least one other unidentified customer.

In the case of Myanmar, an internal report shows the simultaneous monitoring of over 80 million connections across 26 connected data centers, with functions aimed at blocking over 280 VPNs and 54 priority applications, including the messaging apps most used by local activists.

In Pakistan, the Geedge platform has even replaced the Western vendor Sandvine, reusing the same hardware but replacing the software stack with a Chinese one, alongside Niagara Networks components for tapping and Thales for licensing. This is an emblematic case of how Beijing manages to penetrate already saturated markets by exploiting the modularity of its solutions.

Another crucial aspect that emerged concerns the convergence between censorship and offensive capabilities. Some documents describe code injection functions over HTTP (and potentially HTTPS when man-in-the-middle is possible with trusted CAs) and the possibility of launching targeted DDoS attacks against specific targets.

“Kazakhstan (K18/K24) → First foreign client. Used it for nationwide TLS MITM attacks”.

This raises the bar beyond simple information repression: it means having a tool that can censor, surveil and attack, integrating functions that are usually separate into a single platform. This is a real “censorship toolkit” that effectively becomes a cyber weapon at the disposal of authoritarian governments.

The leak of the Great Firewall of China was published by Enlace Hacktivista, a predominantly Latin American hacktivist group – which collaborates with DDoS Secrets – known for having already released other important data leaks such as those of Cellebrite, MSAB, military documents, religious organizations, corruption and sensitive data, and tens of terabytes of companies working in the mining and oil sectors in Latin America, thus exposing corruption and illicit environmentalism, corruption, as well as sensitive data.

In the case of the Great Firewall of China Fierwall Leak the documents were uploaded to their platform – https://enlacehacktivista.org – hosted by an Icelandic provider, known for protecting privacy and free speech.

The first question we should ask ourselves is: why a majority group Should a Latin American company compromise China’s international reputation by publishing sensitive and critical information, likely from an internal source linked to Chinese digital censorship? Who would be behind it? Who benefits from all this? The leak is strategic and has moved simultaneously in multiple directions with targeted action on multiple sources with political impact.

The answer, in the context of an international fight against censorship and digital surveillance, would seem obvious. However, it must be considered that in addition to activists, political opponents, NGOs, and journalists who seek to denounce violations of freedoms and push for sanctions against companies that provide repressive technology, Western governments are trying to limit Chinese influence in the surveillance technology market while increasing geopolitical pressure on Beijing.

‘China views the management of the Internet as a matter of national sovereignty: with measures aimed at protecting citizens from risks such as fraud, hate speech, terrorism, and content that undermines national unity, in line with socialist values.’ However, the Great Firewall of China would not only control the Internet in the country, but its model – along with the technology – would have already been exported outside the country, “inspiring” authoritarian regimes and governments in various regions, including Asia, Africa and finally Latin America, where censorship, digital repression and information control are increasingly widespread:

All this, however, is happening in a climate where the governments of various countries, from Nepal to Japan, passing through Indonesia, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, are facing strong social tensions, which have led to instability triggered by measures such as restrictions on social networks or popular protests. An emblematic case is what happened in Nepal in recent days and a related case is that of Japan, where the change of leadership is moving towards a pro-US attitude.

The A leak of the Great Firewall — a symbol of state control and Chinese technological sovereignty —would go further, affecting the very core of the social contract between the CCP and Chinese citizens—with implications for privacy and national security— thus threatening China’s ambitious plans to make the country a global center of technological innovation. Huawei, Xiaomi, BYD, and NIO are just a few names spearheading this strategic goal, which effectively aims to export cutting-edge technologies in key sectors such as artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, renewable energy, semiconductors, 5G, aerospace, and biotechnology. Well, it’s not just about freedom of speech, because the Firewall protects the Chinese digital market from external competition. Furthermore, a leak would expose the system’s technological vulnerabilities, undermining its reputation or making it vulnerable. And in fact the leak would have been part of the work, not only desacralizing China’s technological invulnerability, but undermining internal trust.

On the other hand, today, September 15, even the announcement of the Chinese antitrust investigation on Nvidia – for alleged violations of the antimonopoly law in relation to the acquisition of the Israeli company Mellanox Technologies – could represent damage to American soft power in the technology and artificial intelligence sector.

The official and media reactions of China confirm the situation: communications are managed with the utmost confidentiality. Caution, with heavy social media censorship and generative AI to limit the spread of information with the help of OSINT specialists and networks like “Spamouflage.” The response was likely. The next step could be damage to international relations, potential sanctions, and increased scrutiny of Chinese tech. Furthermore, some telecom companies examined in the report, including Myanmar’s Frontiir, denied using Chinese surveillance technology or downplayed its use, claiming they were using it for ordinary, legitimate security purposes, with the support of their international investors.

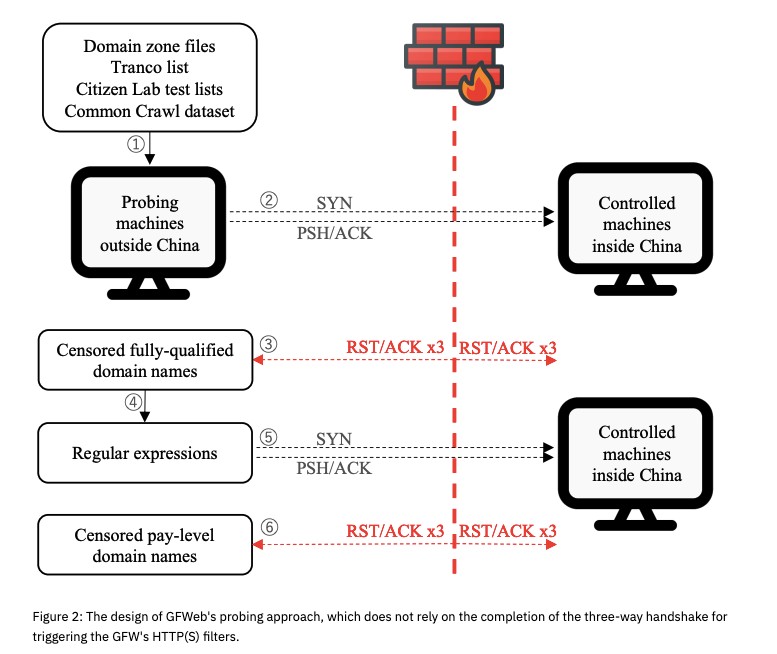

A 2024 study published by USENIX – Measuring the Great Firewall’s Multi-layered Web Filtering Apparatus – has already examined how the Great Firewall of China (GFW) detects and blocks encrypted web traffic. The research was conducted by an international group of university and independent researchers, including the two lead authors, Nguyen Phong Hoang, Nick Feamster, joined by researchers Mingshi Wu, Jackson Sippe, Danesh Sivakumar, Jack Burg.

The goal was to understand the technical mechanisms by which the GFW manages, inspects, and filters HTTPS, DNS, and TLS traffic, especially to circumvent advanced encryption technologies such as Shadowsocks or VMess. The work relied on real-world measurements using VPS servers in China and the US and monitoring tools to study the censorship and blocking operated in real time by the GFW.

In short, the conclusions established that DNS, HTTP and HTTPS filtering devices together constitute the main pillars of the Great Firewall (GFW) web censorship: over the course of 20 months, GFWeb has tested over a billion qualified domains and detected 943,000 and 55,000 censored pay-level domains, respectively.

Research published in 2024 and reports on leaked documents offer an unprecedented amount of inside material, useful for understanding in detail the architecture, development processes and day-to-day operational use of the technology.

The leak exposes several key points:

For those studying security and evasion techniques, this leak represents a goldmine of information. Analysis of the sources could reveal vulnerabilities in deep packet inspection (DPI) algorithms and fingerprinting modules, opening up avenues for developing more effective bypass tools. But it is clear that the challenge is becoming increasingly asymmetric: the counterpart is no longer improvised, but a technology industry with roadmaps, patches and customer support.

The implications The implications of the Great Firewall Leak are enormous, both technically and politically. For the CTI community and those working on digital rights defense, this could be an opportunity to better understand the architecture of next-generation censorship and surveillance and anticipate its future. But above all, it confirms that the battle for digital freedom is no longer played out solely on the terrain of technology, but rather on the even more complex terrain of geopolitics.

Digital censorship is at the heart of power relations between states, and the fight for free access to information is a global and multi-level issue.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.