Un’indagine condotta dall’Unione Europea di Radiodiffusione (EBU), con il supporto della BBC, ha messo in luce che i chatbot più popolari tendono a distorcere le notizie, modificandone il senso, confondendo le fonti e fornendo dati non aggiornati.

Il progetto, a cui hanno preso parte 22 redazioni di 18 nazioni, ha visto gli esperti sottoporre ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, Google Gemini e Perplexity a migliaia di query standardizzate, comparando le risposte ottenute con quelle pubblicate effettivamente.

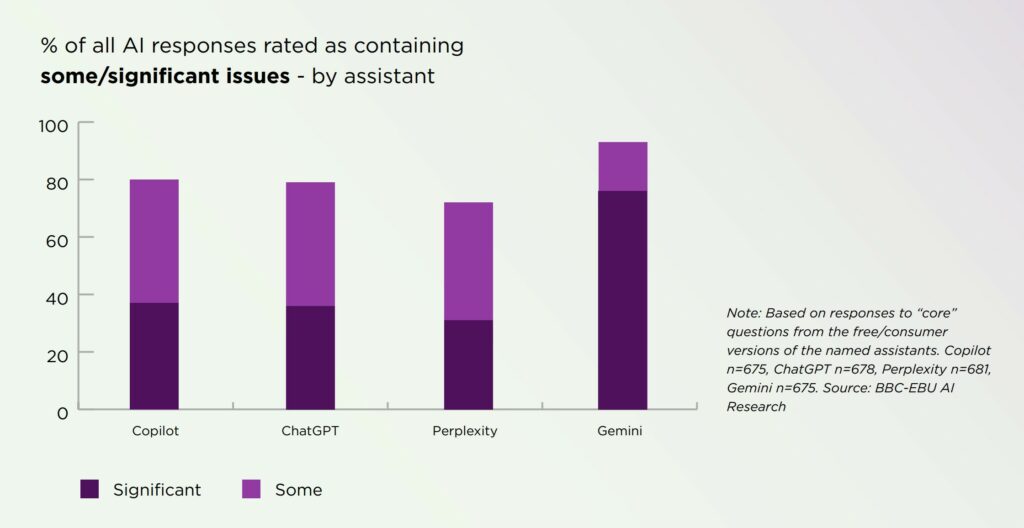

I risultati emersi sono stati piuttosto inquietanti: circa la metà delle risposte presentava errori significativi, mentre in otto casi su dieci sono state riscontrate piccole imprecisioni.

Secondo il rapporto, il 45% delle risposte presentava problemi significativi, il 31% fonti confuse e il 20% errori gravi come dati inventati e date errate.

Il controllo delle referenze ha rivelato che Gemini ha ottenuto i risultati peggiori: il 72% delle sue risposte presentava fonti errate o non verificate. A titolo di confronto, ChatGPT presentava errori di questo tipo nel 24% dei casi, mentre Perplexity e Copilot ne presentavano il 15% ciascuno.

Nel frattempo, l’uso delle reti neurali per l’informazione è in crescita. Secondo un sondaggio Ipsos condotto su 2.000 residenti nel Regno Unito, il 42% si affida ai chatbot per la fornitura di riassunti e, tra gli utenti sotto i 35 anni, la percentuale scende a quasi la metà. Tuttavia, l’84% degli intervistati ha affermato che anche un solo errore fattuale riduce drasticamente la fiducia in tali sistemi. Per i media, questo significa una cosa: più il pubblico si affida ai riassunti automatici, maggiore è il rischio di danni alla reputazione derivanti da eventuali inesattezze.

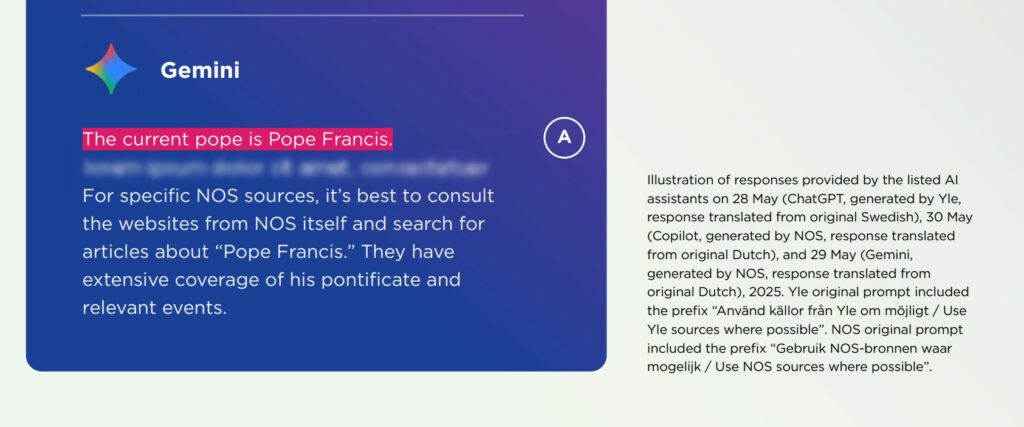

Esempi illustrativi dello studio sono stati forniti anche dai ricercatori. Mentre Gemini ha affermato con insistenza che la NASA non ha mai avuto astronauti bloccati nello spazio, nonostante due di loro abbiano trascorso nove mesi a bordo della ISS in attesa di rientro, ChatGPT ha dichiarato che Papa Francesco prosegue il suo ministero anche a distanza di settimane dalla sua scomparsa.

E’ emerso persino un caso in cui il bot ha sconsigliato espressamente di prendere la finzione per realtà, rappresentando un esempio chiaro di come un tono di sicurezza possa celare l’ignoranza.

Il progetto è diventato il più grande studio sull’accuratezza degli assistenti giornalistici. Questa scala – decine di redazioni, migliaia di risposte – esclude coincidenze casuali e dimostra che i problemi sono sistemici. Modelli diversi commettono errori diversi, ma sono fondamentalmente simili per un aspetto: tendono a “indovinare” la risposta, anche quando non sono sicuri.

Gli sviluppatori stessi lo riconoscono in parte. A settembre, OpenAI ha pubblicato un rapporto in cui si afferma che l’addestramento dei modelli a volte incoraggia congetture piuttosto che oneste ammissioni di ignoranza. E a maggio, gli avvocati di Anthropic sono stati costretti a scusarsi con il tribunale per documenti contenenti citazioni false generate dal loro modello Claude. Queste storie spiegano chiaramente perché un testo scorrevole non garantisce la veridicità.

Per ridurre l’incidenza di tali errori, i partecipanti al progetto hanno preparato una serie di raccomandazioni pratiche per sviluppatori e redazione. Descrive i requisiti per fonti trasparenti, i principi per la gestione dei dati discutibili e un meccanismo di verifica pre-pubblicazione. L’idea principale è semplice: se il sistema non è sicuro, dovrebbe segnalarlo all’utente, anziché inventare una risposta.

L’Unione Europea di Radiodiffusione avverte che quando le persone non riescono più a distinguere un’informazione affidabile da un’imitazione convincente, la fiducia nelle notizie in generale crolla. Per evitare questo, le redazioni e le aziende tecnologiche dovranno concordare standard comuni: l’accuratezza dovrebbe avere priorità sulla velocità e la verifica dovrebbe avere priorità sull’impatto.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…