Today is World Children’s Day, established by the UN on November 20 to commemorate two fundamental acts: the 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child and, thirty years later, the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child.

An event that, every year, risks becoming a ritual gesture, a sterile reminder of the “right to the future.”

Yet the present tells us that true fragility lies not in the future, but in the way children live today: in a digital ecosystem that wasn’t designed for them, fails to protect them, and exposes them to risks that no longer resemble anything we knew.

In recent years, international research, from OECD reports to the technical documentation of the Internet Watch Foundation, has increasingly highlighted a phenomenon we continue to overlook: minors are no longer occasional users. They are immersed in the internet, within systems designed for adults and according to logics that completely ignore what it means to be vulnerable at age eleven or twelve.

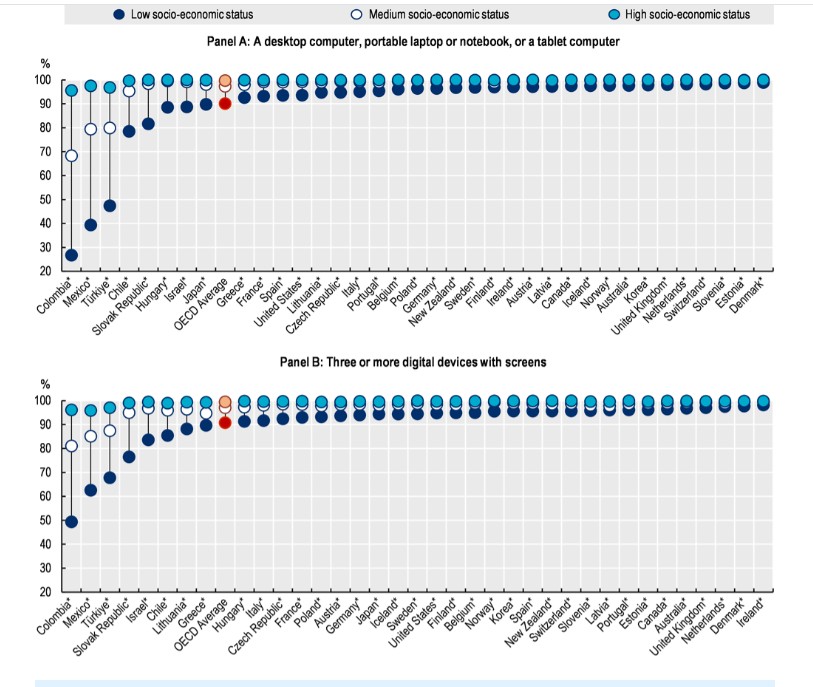

According to the OECD, over ninety-five percent of adolescents in Western countries access the internet every day, often multiple times a day. This isn’t simply “intensive use,” but rather constant exposure to platforms where identities and intentions are never fully discernible. The internet has become the primary space for connection, play, discussion, and discovery. But it remains an environment designed to maximize attention and permanence, not to reduce risks.

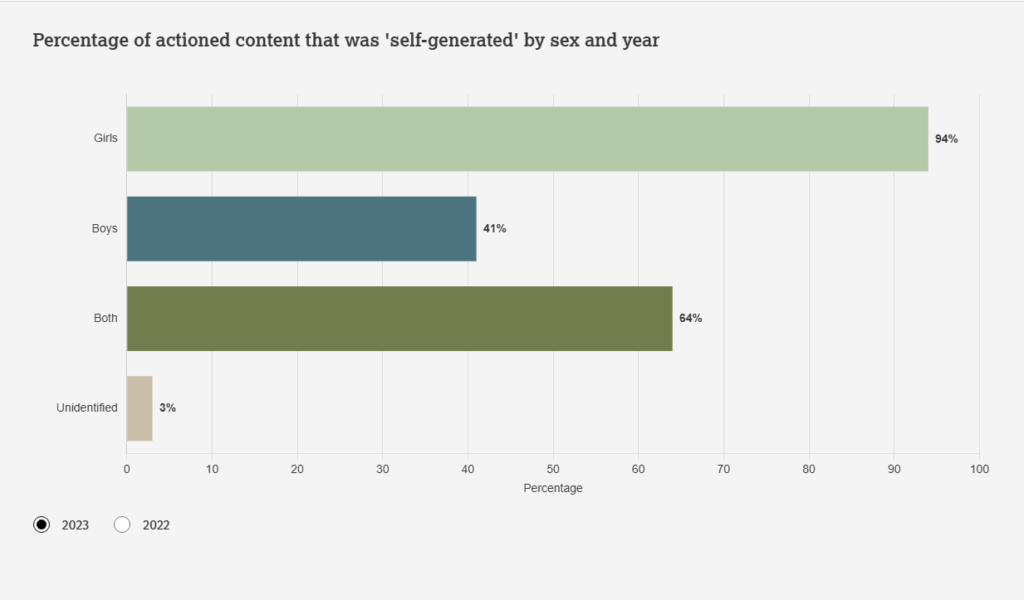

The Internet Watch Foundation, in its 2023 report, analyzed 275,652 web pages containing child sexual abuse material. Over 92% of these were classified as “self-generated” —a term the IWF itself calls inadequate because it doesn’t reflect the reality of the facts. In many cases, children are deceived, manipulated, extorted, or even recorded without their knowledge by someone who isn’t physically present in the room.

It’s the clearest sign of the transformation underway: abuse no longer comes from a remote place, but infiltrates everyday interactions, within apps used by everyone, within conversations that begin innocuously and then slide into increasingly private spaces. The image of the “digital predator” emerging from the outside is obsolete. Today, the threat is constructed from within relationships, in video game chats, on the most popular social networks, in an ecosystem that makes it easy to approach, persuade, and manipulate. A child shouldn’t seek out risk: it’s risk that he finds, often disguised as normality.

Meanwhile, criminal networks have adopted a much more fragmented operating model than in the past. European investigations—from Europol’s IOCTA reports to INHOPE and IWF documentation—show that the real transformation no longer concerns the initial contact, but what happens next : once the material is obtained, its circulation follows a complex chain , spanning multiple levels of the network.

Data collection increasingly takes place in intermediate spaces , such as private chats or cloud services, while distribution is moving towards closed or encrypted circuits , and only at a later stage, when necessary, into the less accessible layers of the network.

This multi-level mechanism isn’t about baiting, but about diffusion , and drastically reduces the possibility of intercepting direct traces. Every anomaly, however small, becomes a valuable clue.

The scale of the problem is also evident in what happens on what we consider “ordinary” platforms. In recent days, Telegram’s official “Stop Child Abuse” channel has published a series of updates that are hard to ignore: 1,998 groups and channels closed on November 15th, 1,937 on the 16th, and 2,359 on the 17th. In three days, more than six thousand spaces were dedicated to sharing or circulating abusive material. This month, the number has already exceeded thirty-six thousand closures.

These aren’t dark web numbers, and they don’t concern underground networks. These are groups visible enough to be detected, reported, and removed every day. The number doesn’t just tell the story of severity. Above all, it tells the story of continuity: every removal is replaced by new openings, with structures that rebuild in a matter of hours, often automatically, often with the same administrators, often with the same content migrating from room to room.

These data starkly demonstrate what public debate still struggles to acknowledge: the problem isn’t confined to the peripheries of the internet. It’s an integral part of the digital infrastructure we all use, every day. And it’s precisely this proximity—silent, normalized, technically invisible to those who don’t seek it—that makes child protection a structural, not an emergency, issue.

In this context, a crucial part of combating abuse remains almost invisible: victim identification . It’s a silent task, made up of details—an object in the background, a recurring piece of furniture, a visual fragment that reappears elsewhere—reassembled until they reveal a place, a real situation, a person in need of protection.

And this is where much of the investigative work is concentrated today. Identifying a victim much more often allows us to also reach the perpetrator. The reverse is not always true : an account may be identified, but the minors involved remain nameless, without context, without a scope for intervention.

This work doesn’t produce announcements or spectacular operations, but concrete results. Every time a child is located, the initial trace was almost always a detail that no one would have noticed. It’s a process that can’t be seen; only the effects are visible.

Making the picture even more complex is the widespread introduction of generative artificial intelligence. It doesn’t take alarmism to recognize that a single public image is enough to create, manipulate, or distort content that the minor never produced . The harm no longer occurs only through what is asked of children, but through what technology can construct on their behalf . It’s a vulnerability that exists even when the minor takes no action .

All this brings us to a key point: protecting minors isn’t just a matter of digital education. It’s, first and foremost, a question of architecture. Platforms were created to incentivize sharing, not to prevent abuse. Algorithms optimize engagement, not security. Reporting systems are reactive, not preventative. And the answer can’t be trivialized by the idea that an age check, SPID access, or an entry filter are enough. Vulnerability doesn’t arise from logging in: it arises from what happens within the platforms , from how interactions are shaped, from which dynamics they favor or ignore.

Reducing child safety to an authentication issue means looking at the front door and ignoring everything that happens inside. Real protection lies in invisible processes: in the criteria by which algorithms decide what to display, in the limits imposed on interactions, in the ability of platforms to detect anomalous behavior before it becomes harmful.

If World Children’s Day still has any meaning, then today must become the moment we accept that the internet is not a neutral space and that children’s rights in the digital environment cannot be recommended: they must be designed . As long as platforms continue to treat minors as ordinary users, as long as algorithms continue to treat their behavior as signals to be optimized, as long as moderation remains a stopgap and not a structural function, vulnerability will remain systemic.

Digital childhood is not an extension of real childhood. It’s a different terrain, with different risks , built on logics that children and adolescents lack the tools to interpret. And until this gap is bridged, we will continue to celebrate a holiday that speaks of rights, while the world we have built constantly puts them to the test.

Addressing this problem does not just mean “educating children better,” nor “putting more control,” nor expecting families and schools to compensate for limitations that do not depend exclusively on them.

It means redesigning digital so that minors are no longer a side effect of the system.

It means demanding transparency from platforms regarding algorithms , clear limits on interactions , structural controls on contact dynamics , and moderation that intervenes before, not after . It means shifting responsibility onto those who build environments—not those who endure them . It means considering childhood not as a special case, but as a design condition , on a par with cybersecurity, privacy, or accessibility.

And, above all, it means stopping thinking of risk as an accident. Risk is a consequence of design.

Protecting minors in the digital world is not a gesture of care: it is a technical requirement.

And until it is treated as such, we will continue to discuss rights when the system simply does not contemplate them.

Every time someone says “but kids need to learn to defend themselves, they are digital natives and smarter than us” , I remember that in 2025 a teenager has the same executive ability and ability to predict consequences that he had in 1990.

It is the environment that has changed radically, not child neurobiology .

Digital was not “born bad”.

It was born without considering that they would be in it too .

Now we know.

We have no more excuses.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.