I macro movimenti politici post-covid, comprendendo i conflitti in essere, hanno smosso una parte predominante di stati verso cambi di obbiettivi politici sul medio/lungo termine. Chiaramente è stato molto comune un cambio di paradigma rispetto al settore bellico dove l’Europa sta cercando di spostare parte delle risorse degli stati membri e gli USA stanno oramai sempre di più marcando in una posizione economica altamente protezionista utilizzando i dazi come mezzo per ridurre il deficit degli scambi con alcuni paesi chiave, Cina inclusa.

Le recenti decisioni prese dal POTUS Donald Trump riguardo il soggetto economico cinese sono null’altro che la continuazione di decisioni prese nel primo mandato del 2018 che venne accusato dai dirigenti del CCP di voler perpetuare protezionismo nazionalistico andando a danneggiare i rapporti tra i due paesi [1]. Anche le decisioni della Russia hanno generato, nell’immediato, un punto interrogativo sulla posizione della Cina riguardo l’invasione ucraina vista la posizione tiepida di Xi Jinping e dai suoi rappresentanti [2].

Il silenzio cinese si fa sempre più assordante creando una sorta di imbarazzo tra i presenti che preferiscono evitare di porre troppa attenzione su questo stato orientale che si comporta in modo stranamente tranquillo in mezzo a questa serie di avvenimenti globali la quale tutti stiamo assistendo.

Se è pur vero che Jinping preferisce l’ascolto ai metodi comunicativi tipici dei dirigenti occidentali (eg:/ conferenze stampa, dichiarazioni e prese di posizione pubbliche) ciò non implica una assenza di chiarezza sulle direzioni decise per il suo paese (notare che chiarezza non è sinonimo di trasparenza). Xi Jinping ha affermato in diverse occasioni di far diventare la Cina una “superpotenza cyber” [3] con risultati per ora coerenti alle sue volontà.

Per gli USA la Cina è una presenza silenziosa quanto ingombrante che dal 2013 [4] ha reso lo spazio digitale un dominio di rilevante importanza per poter sovrastare i suoi competitor (principalmente paesi occidentali). Il controllo di queste aree si sposta in maniera correlata ma indipendente dal territorio che consideriamo come tradizionale, anche nei tempi di pace la Cina è sempre stata attiva nella rete globale di internet sotto diverse forme.

Queste forme non sono da intendersi unicamente come collettivi APT o realtà puramente offensive, la Cina ha da sempre offerto una alternativa ai prodotti tech occidentali quali telefoni, computer, device IoT e, ultimamente, robotica. Questa crescita di mercato ha permesso di aumentare le capacità di collezionare, inviare ed analizzare dati anche (o meglio, soprattutto) dei cittadini occidentali e non [5][6][7].

La Cina si offre al mondo come un nuovo HUB di innovazione ed efficienza mentre sviluppa il suo profilo digitale offensivo, sofisticato e persistente. Per comprendere a pieno le minacce cinesi bisogna conoscere il paese in alcuni dei suoi aspetti, meccanismi e componenti. La People’s Republic of China (PRC) viene considerata un veterano delle minacce informatiche con presenza fin dal 2002 con APT1 (attribuito alla PLA Unit 61398) [8], in questo articolo cercheremo di esplorare l’ecosistema delle minacce Cinesi e di come si sono evolute nel tempo.

Come si è passati dalle semplici (oltre che brevi) dichiarazioni ad un apparato operativo specializzato e così attivo come quello cinese?

La brevità per questo tipo di domande rischierebbe di farci sottovalutare aspetti rilevanti nel definire le minacce cinesi, le loro capacità sul campo e la vittimologia. Per avere la giusta visione dobbiamo analizzare la Cina nel suo complesso, tale compito non è né semplice né immediato. Nonostante ciò possiamo partire dal modello economico Cinese per poter modellare uno scenario apparentemente chiuso e opaco all’esterno.

Al di fuori delle definizioni esemplificate dove vedono l’equazione “Cina = comunismo” (il nome del partito a capo del governo lascia facile confusione), se proprio vogliamo assegnare un’etichetta alla Cina attuale è quella del “Socialismo“ la più adatta. Xi Jinping ha cercato di promuovere l’innovazione nel modello economico della sua politica individuando la cooperazione tra pubblico e privato come leva per poter aumentare il proprio GDP ed aumentare il potere d’acquisto dei propri cittadini. In breve, il CCP si identifica come organizzazione comunista ma le loro policy migrano verso un socialismo “modernizzato” per affrontare le sfide attuali.

Il PRC sta attuando uno spostamento da una economia centrata sull’esportazione di beni ad una basata sui consumi interni incentivando un modello circolare nello spostamento di denaro/beni [9].

In questo (specifico) modello economico le aziende esistono grazie a sussidi e movimenti da parte del governo lasciando però libertà decisionale ai privati. Questo ambiente vibrante è accompagnato da una serie di aziende appartenenti/partecipate dal governo Cinese e da altrettanti scenari misti, il CCP ha inoltre controllo dell’accesso sul mercato alla quale per aderire bisogna essere allineati con gli obbiettivi preposti consolidando partnership pubblico-privato.

Il CCP contiene circa il 7% della popolazione cinese (+100 MLN) permettendo di includere differenti archetipi del tessuto socio-economico del paese, inoltre la linea tra appartenenza statale e privata si fa sempre più opaca grazie ad una legge che deve permettere allo stato di inserire delle “celle” del CCP (o che esplicitamente portino avanti attività del partito) all’interno delle aziende private (anche straniere ma con sede in Cina) lasciando un punto interrogativo sul ruolo di quest’ultime [10][11][12][13][14].

Un secondo (ma non secondario) aspetto dell’economia Cinese è il Five-Year Plan (piano quinquennale) ovvero una serie di iniziative, proposte e piani per lo sviluppo economico e sociale rilasciato dal CCP ogni 5 anni. Tale metodologia e pianificazione risale al 1953 e quello in essere (2021-2025) è il 14esimo nella storia del PRC (People’s Republic of China). Per evitare di essere prolissi non copriremo per intero i contenuti dei Five-Year Plan e daremo solamente uno sguardo ad alto livello.

All’interno del documento quinquennale si trovano le responsabilità e posizioni che il governo dovrà affrontare nel periodo in questione oltre ad una bluperint sui flussi economici e di sviluppo del paese [15][16][17]. Esplorare a pieno (per quanto possibile) questo piano e metterlo in correlazione con le campagne APT cinesi all’estero ci permette di ordinare e chiarificare l’organizzazione di queste minacce e la loro implicazione per potenziali previsioni di attacchi ad asset specifici [18].

Il 12esimo piano quinquennale cinese si è focalizzato sul ristrutturare la domanda interna introducendo fondi di aiuto sociale per potenziare il flusso interno e garantire stabilità sulla domanda interna. Particolare interesse deve essere posto sulla volontà del CCP di creare un’industria tecnologica che potesse rendere la Cina indipendente dalle importazioni di componenti tecnologiche estere e per questo motivo il settore ICT venne incluso nella lista delle “7 Industrie Strategiche Emergenti” incentivando la creazione di sistemi cloud, circuiti integrati, software e distribuzione di banda larga alla popolazione ed aziende [19][20].

In questo periodo storico il paese cinese è riuscito ha diminuire il gap con le altre potenze mondiali in questo specifico settore cercando di proiettare queste nuove conoscenze negli anni a venire. I 7 settori chiave del 12esimo piano quinquennale sono i seguenti :

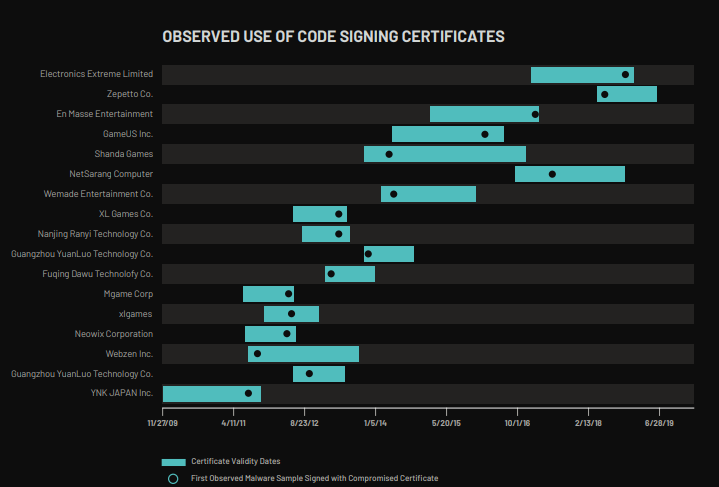

Il primo attore a comparire è APT41 (a.k.a Double Dragon, Winnti; operativo dal 2011/2012)[21] con campagne ad aziende occidentali appartenenti al settore videoludico [22]. Questa prima parte della campagna aveva come obiettivo il furto di certificati ad aziende come KOG, Neowiz (Korea del Sud) e YNK (Giappone). I certificati sono poi stati utilizzati per firmare eseguibili dei malware usati dall’APT stesso ed altri attori cinesi [23]. Nella sua fase embrionale APT41 ha dato linfa vitale per portare le campagne offensive cinesi ad un livello superiore.

Questo primo periodo (1/2 anni) di continuo focus nel settore gaming (incluse case di distribuzione e case di sviluppo), che si sono estese almeno fino al 2014, ha anche portato alla compromissione di macchine contenenti codice sorgente dei prodotti in produzione, sistemi di pagamento, compromissione delle supply-chain e, in alcuni casi specifici, anche deployment di ransomware (più avanti nell’articolo copriremo meglio questo aspetto).

Dal 2013 Double Dragon ha iniziato vere e proprie operazioni di spionaggio nel settore high-tech, farmaceutico, healthcare, energia e governativo in almeno 14 stati diversi. Questo APT si è focalizzato fortemente sul settore ICT ed high-tech con goal finale quello di ottenere accesso a proprietà individuale ed industriale in questo settore. Più di 100 aziende del settore delle telecomunicazioni, tecnologia e sanità sono state impattate dalle campagne di APT41 in questo periodo.

Sempre nel 2013 un’altra entità offensiva cinese ha aderito a supportare il Five-Year Plan in essere con obiettivi simili a Double Dragon, APT40 [24] (a.k.a Leviathan; formatosi circa nel 2009) ha avuto un ruolo importante nelle azioni su paesi strategicamente rilevanti per la Belt & Road Initiative (BRI/B&R) [25] ovvero quel piano di sviluppo commerciale firmato dalla Cina nel 2013 stesso che mirava alla creazione di infrastrutture per connetter Cina, Asia Centrale ed Europa tramite percorsi via terra e mare. Secondo la Cina la BRI doveva favorire ed incentivare patti commerciali, miglioramenti logistici e scambi culturali tra i paesi in questione. Ovviamente questa iniziativa geopolitica rientrava nel 12esimo Five-Year Plan cinese e Leviathan ha giocato un ruolo fondamentale per il controllo digitale delle zone in questione.

In questo periodo APT40 ha pesantemente bersagliato il settore marittimo che possiamo suddividere in due macro aeree principali : la parte di R&D e l’industria di spedizioni via mare. Questo focus è rimasto anche negli anni successivi a questo preciso Five-Year Plan [26][27]. Anche questo tipo di campagne erano focalizzate sul furto di informazioni sensibili dal punto di vista strategico e logistico. Più nel dettaglio questo APT ha conseguito azioni offensive nella zona del Mare Cinese Meridionale attraversata da 1/3 delle merci globali [28].

Interessante notare che questa zona geografica era diventata un soggetto di tensioni politiche e militari che hanno portato la Cina e i paesi ASEAN ha firmare un accordo di condotta che mirava ad evitare comportamenti che potessero portare ad escalation promuovendo risoluzioni pacifiche (2002) [29]. La Cina tramite APT40 ha trovato una zona grigia (o comunque “accettabile” per evitare di creare situazioni di tensione tra i paesi in questioni) per poter effettuare operazioni di spionaggio portando a loro un vantaggio rispetto ai paesi ASEAN.

Queste operazioni permettevano di avere un potenziale di vantaggio strategico estremamente rilevante andando a comprendere i percorsi marittimi per il commercio, il tipo di merci trasportate e tattiche di decisione del prezzo. Avere le mani su questo tipo di informazioni consente scelte economiche e politiche che possono manipolare ed influenzare a proprio vantaggio il commercio marittimo (che ricordiamo comprende circa l’80% delle merci trasportate nel commercio mondiale). Con non eccessiva sorpresa nel 2015 il settore marittimo Cinese, grazie al 12esimo piano quinquennale, è cresciuto di molto [30] coprendo un ruolo fondamentale per la Cina ed i suoi alleati commerciali .

Per quanto concerne il settore R&D marittimo diverse università, organi di ingenerai e di difesa marittima [31][32] sono cadute vittima di Leviathan facendo ottenere all’APT file e dati utili per la costruzione di mezzi marini sia militari che non. La potenza militare cinese deve fare affidamento ai reparti della marina sia per i suoi interessi politici (eg:/ Taiwan, la presenza USA su coste del mare cinese meridionale) che economici, proprio durante questo periodo la flotta cinese ha superato (in numeri) quella USA permettendogli di avere maggiore presenza nel territorio blu [33][34].

Sempre APT40, secondo fonti statunitensi [35], avrebbe in questo periodo iniziato ad interessarsi ad esfiltrare segreti commerciali di tipo sanitario riguardanti anche le tecniche di sequenziamento genetico.

Infine APT1 [36] (a.k.a Unit61398; osservato per la prima volta nel 2002) ha giocato un ruolo più aggressivo negli USA andando ad impattare circa 141 organizzazioni appartenenti a 20 settori diversi (secondo la CISA) [37]. A partire dal 2013 APT1 ha rubato terabyte di dati dalle organizzazioni appartanenti all’automotive (in particolare informazioni su sviluppo di mezzi elettrici ed ibridi), ICT, BioTecnologie, Medical Equipment, tecnologie a basso impatto ambientale, ed altri prodotti che rientrano nel 12esimo Five-Year Plan.

Secondo le indagini di incident response, Unit61398 è riuscita ad ottenere persistenza per almeno 365 giorni all’interno delle reti mentre trasferiva alte quantità di dati su server sotto il loro controllo. La maggior parte delle vittime (totali) di APT1 sono (o hanno sede principale in paesi) di lingua inglese.

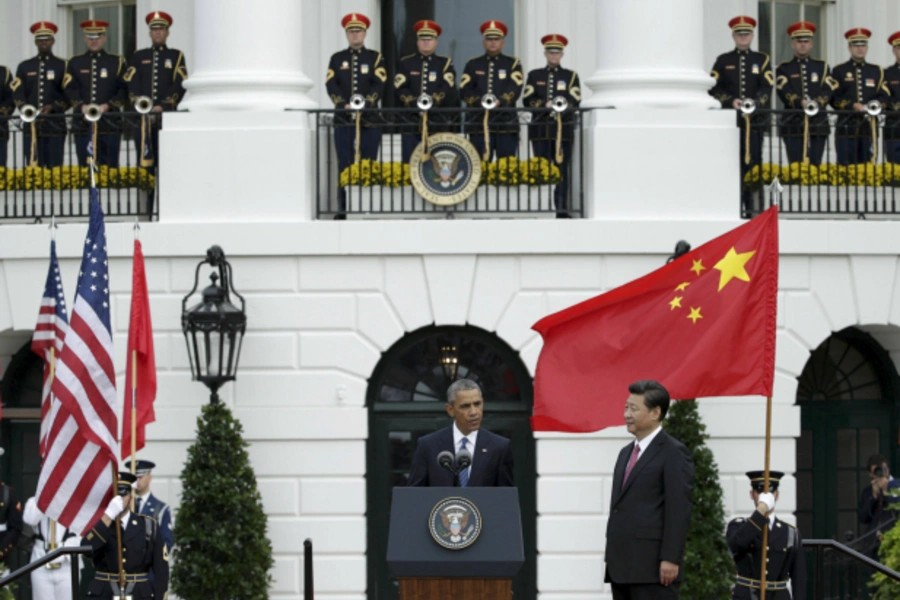

Per concludere questa prima (sotto)sezione non si può non riportare l’incontro tra Xi Jinping e Obama nel 2015 la quale si concluse con un accordo tra i due paesi sul cessare qualsivoglia operazione offensiva digitale sui corrispettivi territori [38][39], nello specifico i due paesi promettevano l’un l’altro di proibire il furto di proprietà intellettuale. Nell’Aprile del 2015 un APT cinese (non meglio riconosciuto) avrebbe penetrato le difese dell’OPM (Office of Personnel Management) [40][41] ottenendo informazioni su parte dello staff federale degli stati uniti.

Prima di questo specifico Five-Year Plan era già in atto un’operazione di spionaggio digitale cinese a danni di diversi stati tra l’Asia (Cina inclusa) e gli Stati Uniti d’America. Operation Iron Tiger ha radici nel 2010 dove (stando alle indagini) comprendeva vittime nel settore education e governativo/politico di diversi stati dell’Asia mentre dal 2013 gli stessi attori avrebbero spostato le loro attenzioni sul territorio USA nel settore Energetico, Tecnologico, Telecomunicazioni e Manifatturiero adeguandosi ai settori del piano di autosufficienza economica cinese in atto.

Secondo gli analisti il cambio di vittimologia fu abbastanza chiaro con un approccio che puntava alla qualità rispetto alla quantità con un forte uso di social engineer, le vittime condividevano l’essere grandi aziende con legami col governo USA per progetti di difesa, aerospazio ed energia. L’attore dietro a questa meticolosa operazione è stato APT27 (a.k.a Emissary Panda) che ha inaugurato la sua prima apparizione nelle prime fasi di Iron Tiger nel 2010.

Oltre alla oramai ovvia esfiltrazione di proprietà intellettuale le fasi di post initial access comprendevano l’ottenimento di email, documentazione di pianificazione, finanziaria e tutto ciò relativo allo stanziamento di budget. La quantità di dati ottenuti si poggiano sulla scala dei Terabyte che, nelle mani delle giuste aziende, hanno avuto un potenziale da non sottovalutare per quanto riguarda la competizione economica.

Il 13esimo FYP (Five-Yera Plan) cinese ha inciso un ulteriore punto di svolta per il modello economico cinese puntando ad una crescita di qualità oltre che di quantità. Il piano strategico “Made in China 2025” [42], firmato nel Maggio del 2015 e sottolineato come fattore chiave per il futuro del paese, fu messo in atto per potenziare le industrie Cinesi e rinnovare il modello basato (fino ad ora) sulla forza lavoro a basso costo. Le industrie cinesi dovevano inserirsi in un mercato moderno e che si focalizzasse sulla richiesta interna (eg:/ urbanistica) per adempiere una nuova indipendenza industriale del paese.

Oltre alle 7 industrie individuate dal piano precedente sono state sottoscritte 5 strategie per il periodo 2016-2020 :

Oltre alle precedenti, nuove industrie sono state soggette ad agevolazioni statali per poter raggiungere tali obbiettivi tra cui :

Nonostante l’accordo Cina-USA del 2015, APT40 ha continuato le sue attività contro il settore marittimo continuando ad ottenere dati grezzi sulla costruzione di mezzi navali e su trattati commerciali marittimi di stati esteri.

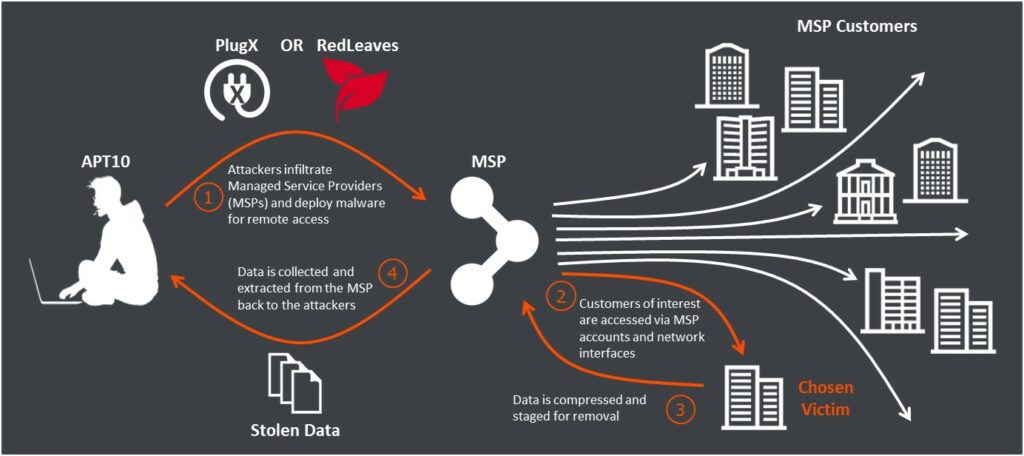

APT10 [43][44] (a.k.a Stone Panda, Red Apollo; prima apparizione tra il 2003 e 2006) ha aumentato la sua capacità ed infrastruttura operativa nel 2016. Nella seconda metà dello stesso anno Stone Panda ha iniziato l’operazione poi denominata Cloud Hopper [45][46].

APT10 ha compromesso diversi MSP (Managed Service Provider, aziende di terze parti che si occupano di mantenere i servizi IT di aziende permettendoli di focalizzarsi sul loro core business) e Servizi Cloud permettendoli di avere accesso a molteplici organizzazioni con una singola intrusione. Dopo le intrusioni gli operatori hanno filtrato le organizzazioni supportate dalle aziende in questione andando a focalizzarsi sui seguenti settori :

I paesi bersagliati sono stati USA, Canada, Brasile, Australia, Sud Africa, Svezia, Svizzera, Paesi Nordici, Francia, UK, India, Sud Corea e Giappone. Il Giappone in particolare ha ricevuto anche operazioni dirette senza passare per terze parti con pretext e file decoy ad-hoc. Come oramai chiaro gli operatori si infiltrarono, grazie all’accesso di MSP/Servizi Cloud, nelle reti delle vittime designate per poter esfiltrare dati, proprietà intellettuale e segreti industriali. Secondo i numeri degli analisti APT10 aveva accesso a potenzialmente migliaia di vittime grazie a questa tattica operativa.

Gli operatori di Cloud Hopper hanno minuziosamente scelto i file da esfiltrare evitando un approccio frettoloso, dati di clienti/privati cittadini non sono stati intaccati dando priorità a documentazione interna o strettamente governativa.

APT27 ha dato il suo contributo direttamente nel 2016 andando a colpire settore energetico e aziende di costruzioni droni in EU [47] e di fatto estendendo l’operazione Iron Tiger iniziata nel 2010 con TTPs simili ma più avanzate. Sempre ad Emissary Panda fu attribuito l’attacco alla sede ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization, agenzia Nazioni Unite) in Montreal [48][49][50] andando ad intercettare l’upload dei file tramite Watering Holes. Ben due enti di indagine indipendente hanno confermato che l’intera rete ICAO fu a disposizione del sponsored threat actor cinese. L’ICAO ha inizialmente tenuto nascosto al pubblico l’attacco che venne poi rivelato da BBC tramite dei documenti da loro ottenuti.

14esimo FYP rilasciato dal CCP, dopo tutti gli sforzi per modernizzare l’industria interna il partito cinese ha preso la decisione di perseguire la strategia della Dual Circulation [51][52][53] (“Doppia Circolazione”). Il governo cinese si è segnato come obiettivo in questi 5 anni di boostare la domanda interna mantenendo però una apertura al mercato globale che ha da sempre caratterizzato il continente orientale. Tali politiche insorgono anche a causa della pandemia COVID-19 che ha limitato di molto il commercio internazionale mettendo alla prova la resistenza di paesi incentrati all’esportazione come la Cina.

La Cina ha compreso la natura ostile dello scenario geopolitico alla quale deve rispondere per mantenere la sua posizione economica in combutta con gli USA.

Le sanzioni del 2018 adottate da Donald Trump [54] (che, a dire USA, furono una risposta al furto di proprietà intellettuale ed altre pratiche commerciali scorrette da parte della Cina) hanno imposto delle barriere economiche alla Cina che diede il via alla guerra commerciale (“Trade War”) tra i due paesi che stiamo assistendo ancora oggi.

Rimuovere la dipendenza da esportazioni permette una maggiore resilienza a cambiamenti bruschi non controllabili dalla Cina, questa fase di bilanciamento fu considerata cruciale per la creazione di una società socialista in chiave moderna. Il CCP rilasciò questo nuovo FYP come un nuovo viaggio per la Cina e la sua popolazione verso una posizione di prosperità economica e sociale.

“high quality development is a top priority in building a socialist modern country…achieving common prosperity…(by) implementing the dual circulation policy.”

Xi Jinping – 20esimo Congresso Nazionale del Partito Comunista Cinese

L’energia verde continua ad avere un ruolo persistente anche all’interno di questo FYP che cerca di ridurre i consumi energetici (ed idrici) per unità di PIL asssieme ad un aumento (prosperato) del tasso di riciclaggio dei rifiuti. Viene inoltre introdotta una serie di obiettivi che possiamo riassumere come “Digital China” ovvero una spinta digitalizzata ulteriore che copre architetture per il 5G, pagamenti digitali, sfruttamento del digitale per processi di governance e strumenti per la società.

I settori chiave individuati, non molto differenti dai precedenti, per il periodo 2021-2025 sono :

Proprio nel 2021 entrò in gioco un attore tra i più invasivi non solo di origine cinese ma degli APT tutti, Silk Typhoon (a.k.a Hafnium) con una campagna ai danni di server exchange tramite 4 0-day all’epoca non ancora identificate [55][56]. Questa campagna non è stata focalizzata su specifici settori industriali ma su una vittimologia più sparsa e meno aderente al FYP rispetto agli anni precedenti.

I settori colpiti rientrano nella difesa, studio di malattie infettive (tra i quali COVID), Tecnologia, NGO ed università. Le analisi hanno svelato un impatto su almeno 30.000 organizzazioni (con analisi che spingono fino a 250.000 vittime [57]) negli USA che tramite le vulnerabilità sono state infettate da malware di tipo web shell per permettere l’accesso degli attaccanti. Dopo il primo contatto gli attori hanno avuto accesso ad email e file che sono stati successivamente esfiltrati tramite MEGA upload. La campagna ha avuto prime tracce nel Gennaio del 2021 con le prime scoperte nel periodo di Marzo.

Interessante l’accesso al settore della difesa da parte di questo attore con dati che contenevano informazioni rilevanti allo sviluppo del settore in paesi occidentali e che si allineano alla richiesta del CCP di una enfasi maggiore sulla sicurezza nazionale. Questo focus ha una importanza anche sul settore digitale visto che il governo cinese ha individuato nella cybersecurity (intesa come strumento sia offensivo oltre che difensivo) un punto fondamentale per poter ottenere un livello di resilienza a minacce esterne. La parola chiave è Technological Self-Reliance che non prevede unicamente il mondo digitale tradizionale ma anche le bio-tecnologie (più volte citate nei precedenti FYP) e costruzione di tecnologie senza (o con minimo) supporto da mercati esteri, la campagna Exchange di Hafnium ha coperto buona parte di questi settori grazie all’uso di 0-day che hanno permesso accessi su larga scala a questa vittimologia specifica.

La Cina si sta spingendo sempre di più per poter ottenere una dominanza strategica e tecnologica dove le operazioni offensive giocano un ruolo importante per mantenere tali risultati.

APT41 è sempre rimasto attivo negli scorsi FYP e anche nella finestra temporale 2021-2025 non è rimasto a guardare, Double Dragon ha perfezionato le sure tecniche ed utilizzate contro il settore healthcare incluso il farmaceutico [58][60]. I metodi rimangono più o meno invariato con primo contatto tramite spear-phishing, watering hole o supply-chain gli attori riescono poi a muoversi all’interno delle reti. Una delle vittime riconosciute nel periodo 2021-2022 fu l’Animal Health Reporting Diagnostic System dove una webapp dell’organizzazione è stata compromessa (0-day), questa webapp veniva utilizzata dal governo per il tracciamento di malattie infettive di animali [61]. Questa operazione permetteva (1) di avere accesso a dati sanitari inclusi PII e, potenzialmente, (2) accesso a reti governative che usavano questa applicazione. Anche organizzazioni healthcare private sono state impattate in questo periodo.

Le minacce cinesi non si sono limitati ai settori tradizionali e stanno puntando in maniera sempre maggiore a figure di alto livello e di campi sempre più specifici, un caso interessante sono i tentativi di accesso perpetrati da APT15 ai danni di SentinelOne tra il 2024 e 2025 [62]. Fortunatamente l’azienda ha contrastato con successo la minaccia riuscendo ad evitare breach o altri tipo di impatto sulle loro reti. Tramite accessi intermedi ad aziende e organi governativi gli attaccanti hanno tentato di abusare risorse di SentinelOne per potersi muover all’interno di asset dell’azienda. Inoltre tentativi di compromissione a stakeholder di SentinelOne che offrivano servizi di logistica hardware sono stati individuati lasciando ipotizzare tentativi di avvelenamento della supply-chain. Non è chiaro la motivazione di tale bersaglio ma tra le diverse ipotesi sono quelle del furto di dati per la comprensione del funzionamento di software/tecnologie per la difesa digitale che rientrerebbe tra gli obiettivi di “resilienza” cinese in chiave informatica.

Questo ultimo esempio dimostra come non ci siano limiti per attori nazionali/statali (al contrario del ransomware che si focalizza sulle medio/piccole aziende) e che avendo virtualmente infinite risorse possono permettersi di persistere su singoli target nonostante la loro grandezza o natura.

Tutti gli esempi portati in precedenza servono a sottolineare, con alcuni esempi fattuali, come il FYP dia linee guida non solo alle industrie e mercato interno cinese ma anche ai suoi APT. Rimanere aggiornati sul FYP attuale permette di avere qualche grado aggiuntivo per la prevenzione di vittimologie che potrebbero rientrare nell’interesse di minacce cinesi che impattano sia in occidente sia ai loro vicini in oriente.

Ovviamente non ci sono sufficienti indizi per poter anche solo ipotizzare una lista di settori fondamentali, nonostante ciò uno studio preliminare per il 15esimo FYP è stato eseguito nel Dicembre 2023 dalla National Development and Reform Commission [63] (NDRC, Commissione per lo sviluppo e riforme nazionali) cinese. L’NDRC ha sottolineato come il tessuto socio-economico cinese abbia ancora innumerevoli colli di bottiglia (come quelli dell’energia rispetto alla Carbon Neutrality richiesta dal CCP) da risolvere per poter affrontare le sfide dei prossimi cinque anni richiedendo analisi e pianificazioni in anticipo rispetto al passato.

Oltre all’energia, la commissione ha individuato una necessità sull’offrire una ulteriore crescita dell’economia privata che non si è ancora totalmente bilanciata tra economia domestica ed esterna. Infine la parte nord della Cina, sempre secondo il NDRC, dovrà avere assegnato diversi progetti per la creazione di terreni agricoli supportati dalle nuove tecnologie.

Xi Jinping ha da sempre dichiarato che lo sviluppo tecnologico deve essere la chiave di volta per la stabilità economica del paese, i dazi della amministrazione Trump potrebbero accelerare settori “nuovi” (IA, Quantum Computing) che possono andare a supportare altri settori che la Cina sta cercando di rendere indipendenti da stati esteri (quali agricoltura, medicina e tecnologia).

“it is essential to proactively assess how changes in the international landscape affect China and to adapt accordingly by adjusting and optimizing the country’s economic structure”

Xi Jinping [64]

Nonostante un piano di indipendenza guidata principalmente da una economia circolare (non ancora raggiunta) il paese cinese conferma la necessità di mantenere un ruolo nel mercato internazionale, la chiave per questo è il settore healthcare.

La Cina ha un grosso problema con la parte più anziana della popolazione che è stata soggetta a diverse malattie, molte delle quali croniche. Questo ostacolo rende difficile la cura e la sanità [65][66] di questa parte della popolazione e, in parte, motiva tutte quelle campagne sul settore sanitario-farmaceutico.

Inoltre Xi Jinping stesso ha espresso interesse nell’ottenere una posizione strategica per la sanità globale incentivando la ricerca e risorse in questo settore sin dagli anni del COVID-19 [67][68]. Puntare su questo settore come merce di scambio globale permette di avere un flusso continuo proveniente dall’esterno e allo stesso tempo un ottimo fattore di soft-power per le risoluzioni politiche. Ricordiamo che mentre gli USA hanno fermato i fondi diretti al WHO (World Health Organization) la Cina ha invece donato ulteriori risorse economiche cercando di mitigare le mancanze da lato statunitense [69].

Questa breve analisi, unita allo studio del comportamento degli APT, serve per ipotizzare ulteriore interesse nelle strutture sanitarie che potrebbero essere soggette a campagne di APT cinesi. Purtroppo il settore healthcare non eccelle per sicurezza informatica e attori con interesse di spionaggio possono sfruttare questa mancanza a loro vantaggio che vengono poi tradotte (nel caso della Cina) in vantaggio economico-politico.

Nella sezione precedente ci siamo inoltrati unicamente in campagne che avevano segnali di interesse economico volutamente ignorando tutte le operazioni con senso politico. Difficile distinguere una linea netta e chiara tra questi due mondi che, ovviamente, tendono a mischiarsi rendendo tale distinzione di fatto solo teorica. In questa sezione cercheremo di affrontare campagne con chiari segnali di spionaggio politico, propagandistico, disinformazione ed influenza.

Partiamo dai vicini di casa della Cina, in particolare quelli con la quale deve condividere il Mare Cinese Meridionale ovvero i paesi ASEAN. Come già discusso nella sezione precedente il controllo di queste acque da un potere economico non da poco oltre che essere un asset importante per la difesa dei paesi bagnati da questo mare.

In questo la Cina ha avuto un approccio duale (oramai tipico dell’élite politica cinese) nell’affrontare dispute politiche di questo tipo, da un lato incentiva un approccio di mutua fiducia [70] e dall’altro da visibilità alla sua posizione privilegiata in confronto ai suoi vicini [71]. Le tensioni in questo territorio blu hanno origini alle dichiarazioni di territorio molto larghe da parte della Cina che venne criticata di “salami-slicing” [72] da diversi organi internazionali.

Per “salami-slicing” si intende una serie di piccole azioni perpetuate nel tempo che vanno ad aumentare gradualmente cercando di apparire meno minacciosi rispetto a movimenti monolitici. Il codice di condotta discusso nel capitolo precedente fu una promessa di evitare escalation privilegiando la diplomazia.

La Cina non ha intenzione di fermare gli sforzi per l’ottenimento di un riconoscimento di questo ricco territorio commerciale e ha optato per un approccio ibrido e “subdolo” assieme a metodi più “muscolosi” [73]. Sempre nel capitolo precedente si può notare una quantità notevole di NGO e think-tank politici presi di mira dai diversi APT, non essendoci un (apparente) motivo economico rimane solo da leggerli in chiave politica.

I “Confucius Institutes” sono delle associazioni culturali esterne ai territori Cinesi dove avviene una promozione culturale decisi dai programmi del Ministero dell’Educazione Cinese. In questi ambienti vengono sponsorizzati programmi di Exchange per studenti e non, condivisione del modello cinese e sulla loro visione culturale-politica. Questi centri hanno creato controversie per via dell cambio della percezione pubblica su influenze politiche ed economiche della Cina, disputa del mare condiviso con paesi ASEAN incluso [74].

Alcuni think-tank politici denunciano l’uso di questi centri culturali per andare incontro al solo beneficio della Cina rispetto a questo conflitto politico [75][76].

Per quanto concerne le NGO invece non si distacca di molto da queste controversie, la Cina è stata accusata di attività illegali riguardo alla pesca in acque distanti dai suoi confini marini [77][78] e le NGO giocano un ruolo di tracciamento di queste attività non regolamentate [79][80]. Non avendo ulteriori informazioni a riguardo è complicato trovare ulteriori motivi ma sicuramente il ruolo delle NGO non è apprezzato dal colosso cinese che ha sempre espresso la necessità di una totale assenza di qualsivoglia attore esterno o non governativo in quelle zone accusando le NGO di fornire potenziale materiale per spionaggio per conto di altri paesi [81].

Ora che abbiamo dato un senso (n.d.a che potrebbe essere errato e basato su fonti pubbliche quindi limitate) a queste due vittimologie rimaste in sospeso possiamo passare ad alcuni casi interessanti dove attori cinesi sono stati implicati in operazioni di spionaggio ed influenza politica.

Campagne di spionaggio di paesi come Malesia, Vietnam ed affini sono stati presenti per almeno 10 anni [82] riconfermando un interesse persistente in attacchi digitali cercando di danzare sulla linea predisposta dal codice di condotta firmato nel 2002 evitando escalation militari convenzionali.

Oltre ai precedenti APT citati, Billbug ha marcato il territorio del sud-est asiatico con attacchi ad infrastrutture critiche ed enti governativi [83][84] con azioni sempre più dannose specialmente per il controllo del traffico internet [85] di questa zona creando un danno alla sicurezza nazionale delle vittime in questione. Ad oggi Billbug sembra non cedere a smettere azioni in questa regione del mondo.

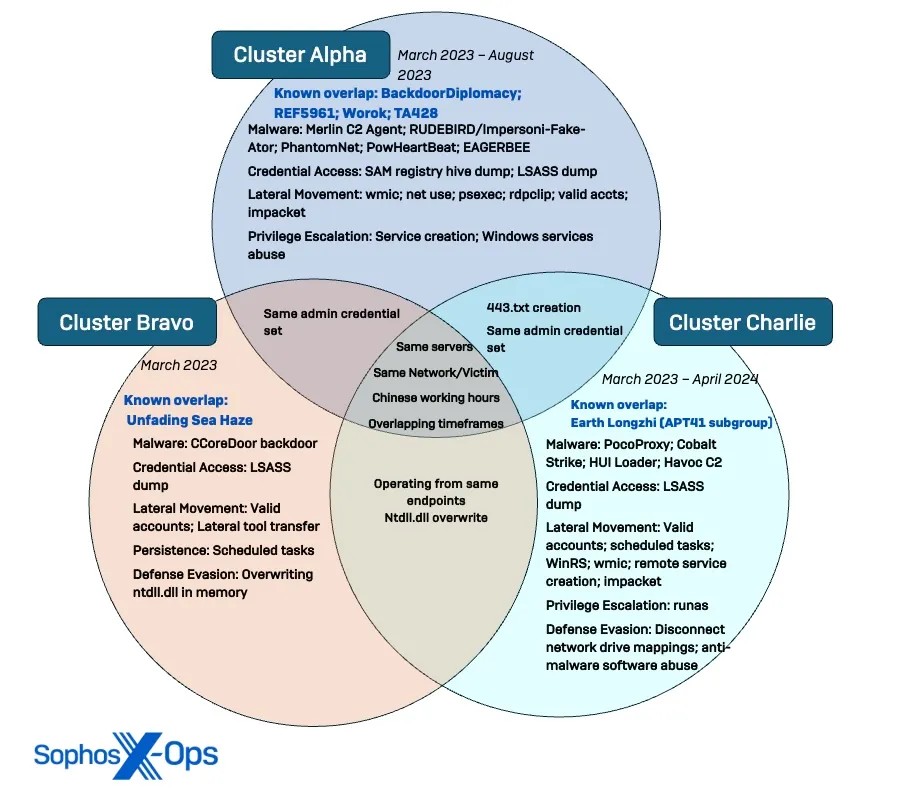

Le minacce vanno anche al di fuori dei semplici APT includendo veri e propri cluster [86] di attori in operazioni contro governi sud asiatici con presenza all’interno delle reti di diversi anni prima di essere scoperti e rimossi.

I paesi che devono condividere il territorio blu del sud-est asiatico non devono solo convivere con gli APT di matrice cinese ma anche con la propaganda che viene riproposta sotto diverse forme. Riuscire a controllare e/o manovrare l’opinione pubblica cercando di favorire l’influenza della CCP avviene in maniera subdola e molto meno diretta rispetto ad altre nazioni.

A metà 2024 un deepfake audio, accompagnato da una serie di immagini di navi cinesi, di Ferdinand Marcos Jr (presidente delle Filippine) è circolato nel territorio filippino [87]. In tale audio il (fake) presidente eseguiva una sorta di chiamata alle armi contro una nazione non meglio specificata. Il nome “Cina” non fu presente nell’audio ma la correlazione poteva essere di facile arrivo visto le recenti tensioni (sempre in salsa “salami-slice”) [88] da parte della Cina nelle solite acque contese.

Non fu un episodio isolato quello delle Filippine che si trova ad essere un territorio fertile per la disinformazione cinese [89][90], l’uso di covert-account e dei deepfake hanno di fatto messo in bocca al presidente criticismi riguardo alla collaborazione tra le Filippine e gli US oltre a portare avanti una narrativa di un governo instabile ed indeciso [91][92]. Interferenze con le recenti elezioni (12 Maggio 2025) sono state attribuite ad attori legati al governo cinese [93], il presidente Marcos si è da sempre contraddistinto dalla sua posizione ferma contro l’espansionismo marittimo cinese, la sua collaborazione con gli USA e la richiesta di un “break the silence” globale sul mare sud asiatico [93][94][95][96]. Nonostante la vincita di Marcos nelle elezioni il suo risultato (6 posti su 12 nel senato) fu sotto le aspettative contribuite da delle tensioni con il vice-presidente Sara Duterte.

Disinformazione e spionaggio sono le armi digitali che fanno parte di questa tattica di escalation graduale dove la Cina sembra spingersi fino al limite dei suoi vicini. Non c’è da sorprendersi se questa forte disputa territoriale rimane assente nelle discussioni globali che sono, tra l’altro, focalizzate su altri conflitti molto più caldi e vicini rispetto a quello del Mare del Sud Est Asiatico.

La Cina ha compreso che le operazioni in campo informatico ed ibrido vengono prese in considerazione da una nicchia di persone ed ignorata dal resto dell’opinione pubblica, questo rende possibile agire con prepotenza sempre più crescente senza attirare attenzioni.

Le dispute per la sovranità territoriale cinese si estendono al di fuori di quello puramente marittimo, la situazione tra Hong Kong e Cina ne è un esempio lampante. Nel 1997 Hong Kong, precedentemente colonia Inglese dal 1842, viene restituita alla Cina sottoforma di SAR (Special Administrative Region) ovvero Hong Kong mantiene un certo grado di autonomia mentre la Cina continua a mantenere una sovranità territoriale e politica. Evitando le sfaccettature più complesse Hong Kong mantiene il controllo su :

La Cina invece ha controllo su (principalmente) questi aspetti di Hong Kong :

Ovviamente ci troviamo di fronte ad una situazione complicata soprattutto le diverse proteste fatte dai cittadini della SAR, gli avvenimenti più conosciuti sono Umbrella Movement (2014, richiesta di maggiore trasparenza nei processi democratici) [97] e la serie di proteste pro-democrazia partite nel 2019 che hanno forzato la Cina ad imporre leggi sulla sicurezza nazionale nel 2020.

Qui ci troviamo di fronte ad una grossa spina nel fianco del dragone, i dissidenti politci. Jimmi Lai [98] può essere considerato il “Khodorkovsky” [99] hongkonghese, uomo d’affari e politico pro-democrazia che si è fermamente opposto al CCP che li causò arresti e diverse accuse di frode.

APT31 [100] (a.k.a Judgment Panda) si è contraddistinto per le sue operazioni contro dissidenti e critici del governo cinese. Il gruppo è stato accusato e sanzionato dagli USA per le sue operazioni contro enti, politici ed NGO statunitensi ed UK [101]. Ricercatori hanno scoperto una campagna di infiltrazioni e spionaggio durata per almeno 10 anni con vittime tra le più svariate, tra tutte spiccano le campagne attribuite ad operazioni in risposta alle proteste in Hong Kong del 2019 andando ad impattare i diversi attori coinvolti (inclusi quelli appartenenti ad Umbrella Movement e Amnesty International). L’Inghilterra è uno degli stati che condanna fermamente le azioni di repressioni cinesi sui diritti politici e civili di Hong Kong [102][103] assieme agli USA [104][105] ed altri stati europei [106][107] che sono stati bersaglio di questa serie di operazioni. Le informazioni ottenuto tramite APT31 non sono solo per tracciare dissidenti e critici ma anche per avere conoscenza della reazioni dei vari paesi dopo l’introduzione della legge sulla sicurezza nazionale e successive proteste.

Anche APT41 (DoubleDragon) ha dato il suo contributo concentrandosi sul settore governativo di Hong Kong [108] come parte di una operazione più grande chiamata CuckooBees[109] tra il 2021 e 2022. La presenza di Winnti in entità chiave hongkonghesi permette un controllo politico non indifferente monitorando l’autonomia che Hong Kong nella sua natura SAR.

Buona parte di attivisti e dissidenti provengono dal mondo universitario che, grazie alla autonomia di Hong Kong a riguardo, offre terreno fertile per movimenti pro-democrazia [110][111]. Ovviamente APT41 ha avuto un ruolo importante anche per il monitoraggio di questi ambienti [112].

Oltre ai tipici movimenti APT, per cercare di ostacolare i movimenti dei diversi attivisti in Hong Kong sono stati eseguiti campagne DDoS su larga scala [113][114]. In particolare il forum LIHKG (simil-Reddit) fu vittima, LIHKG venne riconosciuto come uno strumento cardine per l’organizzazione di proteste [115].

Quali sono le dichiarazioni della politica Cinese riguardo alla situazione con Hong Kong? Inizialmente la Cina ha promess il framework “one country, two system” reso formale con la dichiarazione congiunta sino-britannica [116]. La promessa cinese comprendeva il mantenimento del sistema economico in essere e l’autonomia sociale, legale ed economica. Nonostante il trasferimento della sovranità popolare alla Cina i diritti civili dovevano rimanere intatti con una assenza di forzature o influenze politiche. Il framework deve essere mantenuto fino al 2047 (50 anni) dopodiché la Cina avrà completa autorità su Hong Kong e potrà integrala totalmente alla nazione cinese.

Il patto rimase intatto fino a quando Xi Jinping e la sua amministrazione prese la leadership del CCP stringendo l’opposizione di Hong Kong e sottolineando “l’inizio di una vera democrazia” [117] iniziò quando Hong Kong divenne territorio cinese. La promessa fatta nel ’97 iniziò a vacillare dopo le proteste del 2020 (25esimo anniversario del passaggio da colonia Inglese a SAR cinese) quando Jinping dichiarò che il potere politico del SAR deve appartenere a “patrioti” ed evitare che “cada nel chaos” [118]. Proprio dal 2020 le attività APT si fecero più ingombranti e pesanti oltre alla legge draconiana sulla sicurezza nazionale imposta ad Hong Kong e la limitazione dei movimenti di protesta.

La relazione tra Hong Kong e Cina si estende anche all’ONU e paesi occidentali (oltre alle NGO, sempre bersaglio di attori digitali cinesi) rendendo la questione soggetto di critiche verso il paese orientale. L’uso di APT è fondamentale per diminuire il grado di autonomia concessa ad Hong Kong offrendo alla Cina un forte vantaggio di repressione e cambiò di identità graduale [119] voluta da Bejing.

Ovviamente non si può parlare di politica estera cinese senza citare Taiwan. Anche i meno avezzi alla geopolitica orientale sono a conoscenza delle forti tensioni tra i due paesi. Conosciuta anche come Provincia di Taiwan viene considerata, formalmente dalla PRC, una provincia cinese senza però averne mai controllato il territorio, inoltre nonostante abbia un proprio esercito, valuta e governo non viene considerata uno stato sovrano da parte della comunità internazionale.

Taiwan ha da sempre lottato per essere riconosciuta come entità autonoma da il resto delle nazioni mondiali il che rimane un dibattito aperto e molto sentito sia dalla Cina che della isola, gli Stati Uniti d’America supportano (de-facto) il sistema democratico ed autonomo di Taiwan mantenendo però rapporti diplomatici con la Cina riconoscendo la policy “One China” [120]. Un gioco sul filo del rasoio dove tutte le nazioni coinvolte dosano le proprie dichiarazioni ed azioni per disincentivare una escalation militare cinetica.

Sempre per il principio “One China” la PRC non può avere rapporti formali con enti taiwanesi e riconosce come red line per l’uso della forza militare una potenziale dichiarazione formale di indipendenza o interventi esteri a riguardo. Ovviamente vista la locazione geografica, Taiwan non è esente dalla aggressività cinese sul South China Sea il che complica ulteriormente la politica estera di altri paesi (come USA) in quelle zone [121]. L’ultimo aspetto, ma non meno importante, è la produzione ed esportazione di semiconduttori grazie ad una florida industria che domina il mercato mondiale [122][123][124].

Sul battleground digitale Taiwan presenta uno scenario sfaccettato con una forte densità di attività da parte di APT cinesi, si parla di tentativi di infiltrazioni e scam quasi quotidiane [125][126] a diversi settori taiwanesi. Coprire l’intera storia della guerra digitale tra le due fazione richiederebbe una sede a parte ma possiamo concentrarci sullo scenario attuale (2020 in poi) per comprendere le intenzioni del CCP riguardo la situazione con Taiwan.

L’aggressività digitale su Taiwan va ad impattarsi su diverse infrastrutture critiche taiwanesi con un APT nuovo scoperto nel 2023 focalizzato unicamente sul territorio taiwanese, UAT-5918 [127][128]. La particolarità di questo APT sono le sue motivazioni che si distanziano dagli APT tradizionali (eg:/ furto di dati, spionaggio, sabotaggio), UAT-5918 si infiltra nelle reti di infrastrutture critiche per mantenere persistenza sul lungo termine evitando di creare danno o di farsi notare con azioni più rumorose. Se la vittima contiene web application gli operatori APT distribuiscono webshell in ASP o PHP nascondendole nelle directory web (SparrowDoor e CrowDoor).

Le infrastrutture critiche includono :

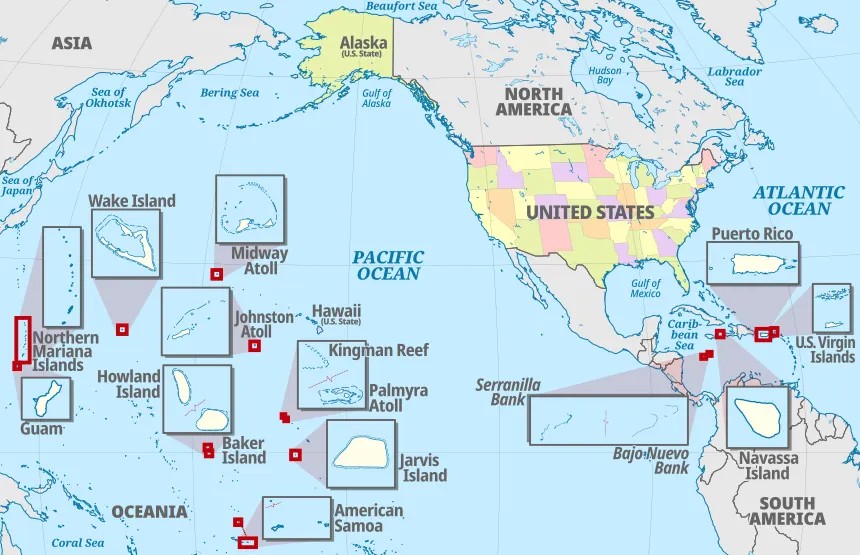

Possiamo notare come compromissioni di questi settori vadano ad impattare sulla società civile e non ad apparati militari. Per quello entra in gioco Volt Typhoon, tra i vari attacchi il più interessante per questa sezione è l’attacco alle infrastrutture critiche in Guam [129] (territorio USA in Oceania).

Con la stessa tattica di UAT-5918, Volt Typhoon ha penetrato ed ottenuto persistenza (con accesso a reti OT) senza interagire ulteriormente con i sistemi. Non solo Guam ma anche altri territori continentali e non-continentali statunitensi sono stati vittima di Volt Typhoon, ovviamente gli USA non hanno rilasciato i territori esatti ma possiamo notare coma la maggior parte di questi (14 in totale) sono presenti in Oceania.

Inoltre nel advisory a riguardo gli USA attenzionano direttamente Canada, Australia, UK e Nuova Zelanda della minaccia Volt Typhoon, tutti questi stati sono partner stabili con la quale hanno relazioni diplomatiche ufficiali e nonostante non ci sia un patto di mutua difesa le relazioni politico-economiche e culturali rimangono molto forti [130][131][132][133][134].

In questo caso le infrastrutture colpite rientrano nei seguenti settori :

In particolare, il settore trasporti e quello delle telecomunicazioni in quei territori (oltre a quelli continentali) sarebbero di fondamentale importanza per una potenziale logistica militare.

Un’ulteriore attore che ha eseguito campagne per l’ottenimento di persistenza in reti critiche è UAT-7237 (attribuito essere sottogruppo di UAT-5918) responsabile di attacchi contro infrastrutture web taiwanesi [135][136] con sempre lo stesso obbiettivo : persistenza su lungo-termine su target di alto livello (non nominati).

Ad una prima lettura potrebbe risultare difficile comprende il perché mantenere persistenza come obbiettivo senza effettuare furto di dati o disruption delle reti. L’approccio cinese sulle infrastrutture civili taiwanesi e logistiche dei suoi alleati è una tattica che può essere intensificata per potenziali operazioni militari su territorio taiwanese.

Altri paesi (inclusi gli USA [137]) hanno considerato persistenza in sistemi critici da mantenere ed utilizzare in maniera congiunta ad operazioni considerati più tradizionali, la Cina si sta solo adeguando ai tempi moderni. Vista la “red line” cinese ed il suo non aver mai tolto dal tavolo la possibilità di forza militare su Taiwan avere accesso ad infrastrutture critiche permetterebbe campagne militari repentine ed efficaci.

Diverse analisi hanno portato alla stessa conclusione dove un ipotetico scontro Cina-Taiwan potrebbe essere iniziare con una invasione (da parte cinese) con un alto impiego di forze preceduto da breve avvertimento [138][139]. Se a ciò aggiungiamo che gli accessi alle infrastrutture critiche permetterebbero confusione tra la popolazione e rallentamenti di ipotetici rinforzi esteri il rischio per Taiwan si accentuerebbe facendo cadere le proprie difese.

Non si sta assumendo né che la Cina stia preparando ad attaccare (la persistenza nelle infrastrutture critiche potrebbe essere stata impiegata in caso di superamento delle “red line” cinese) né che gli stati partner di Taiwan impiegherebbero le proprie forze a difesa dell’isola. Quello che si sta affermando è che se la Cina volesse invadere Taiwan dovrebbe farlo nel tempo più breve possibile considerando tutti i possibili impieghi di forze estere e che per entrare in questa condizione sta utilizzando i propri APT per mantenere un vantaggio temporale dato dall’unione di forze cinetiche e digitali.

Nel caso di Taiwan gli APT non sono semplici attori che vanno ad impattare le industrie e l’economia del paese ma veri e propri avversari militari oltre che politici, la resilienza informatica di Taiwan è fondamentale per il suo apparato di difesa. Tutto questo è accompagnato da operazioni che seppur più “tradizionali” rimangono ancora numerose ed efficaci. Tramite attacchi supply chain APT10 ha mantenuto persistenza per (almeno) 18 mesi nel settore finanziario taiwanese [140] andando ad ottenere informazioni su broker ed investimenti in un periodo di crescita economica, il settore di punta di Taiwan (semiconduttori) che gli permette di avere un peso geopolitico continua ad essere soggetto di interesse per attaccanti cinesi [141] e persino il settore della ricerca governativa [142].

La Cina sta giocando il ruolo dello squalo che nuota attorno alla vittima e non c’è da sorprendersi che lo stesso comportamento si estenda dalla politica al comportamento dei suoi APT che dimostrano una versatilità da non sottovalutare.

Nel periodo recente diversi attaccanti cinesi si sono presentati alle porte dell’Europa e di altri paesi occidentali accendendo il dibattito sul considerare o meno la Cina un nemico per la parte ad ovest del mondo. Gli USA hanno subito una delle operazioni di spionaggio telematico più grandi della storia fino ad oggi [143] [144] eseguito da Salt Typhoon. Lo stesso APT ha eseguito una operazione analoga (ma di dimensione ridotta impattando provider minori) nei Paesi Bassi [145] [146].

Nel caso olandese non sono stati individuati infiltrazioni ma solamente il controllo di device perimetrali e router appartenenti a diverse organizzazioni senza ricevere un impatto diretto, le azioni cinesi non sono passate inosservate ad hanno portato a tutta una serie di paesi occidentali e non a pubblicare un Joint Cybersecurity Advisory tramite le loro organizzazioni per la sicurezza nazionale (tra cui le italiane AISI e AISE) per il contrasto delle operazioni di Salt Typhoon e similari.

Questo peculiare interesse per l’accesso a sistemi di telecomunicazioni occidentali da parte della Cina è difficile da spiegare ma potrebbe non essere diverso dai contenuti che abbiamo coperto in questo articolo. Come già affermato la Cina sta puntando ad diventare una “superpotenza cyber” inoltre il CCP ha sempre voluto affermare la sua sovranità territoriale e politica con una approccio muscolare e provocante. Oltre alle ovvie implicazioni sullo spionaggio su cittadini e politici, le operazioni cyber su territorio occidentali sono un messaggio di potere ed influenza sul territorio digitale come arma politica e militare.

Inoltre, vista la forte connessione tra tattica militare e quella degli APT cinesi, l’accesso a sistemi di telecomunicazione permette di mappare le reti nazionali dando un vantaggio importante per future operazioni.

Gli ultimi avvenimenti non sono un caso isolato e la Cina ha da qualche ha mostrato interesse per il territorio digitale Europeo. Nel 2023 il CERT europeo ha avvisato le organizzazioni di tutti e 27 stati sulla presenza sostenuta di molteplici APT cinesi [147] responsabili (principalmente) di furto di dati sensibili/proprietà intellettuale. Nello stesso anno APT31 ha effettuato una complessa e sofisticata campagna di furto dati all’interno di reti air-gapped nell’Est Europa [148].

Nel 2024 gli gli attori cinesi hanno effettuato la maggior parte delle campagne APT mondiali (secondo ESET [149]) ed hanno esteso ulteriormente i loro sforzi sull’EU.

Apparentemente la Cina ha inizialmente mantenuto il suo interesse nell’Est Europa, l’esempio cardine fu nel 2022 dove APT31 si infiltrò nelle email del Ministro degli Esteri della Repubblica Ceca [150]. Nel 2024-2025 questo trend di intrusioni e spionaggio si è accentuato sul settore governativo ed industriali con campagne sempre più sofisticate e creative [151].

In Europa le minacce principali sono APT31, APT27 e Mustang Panda che gradualmente continuano ad aumentare le loro capacità offensive.

Nonostante il miglioramento economico la Cina mantiene una problematica di sovraproduzione delle sue aziende (in particolare quelle statali) [152] [153] e l’Europa presenta una valvola di sfogo grazie al suo mercato eterogeneo e numeroso.

Il CCP deve puntare all’Europa come un pivot commerciale fisso mantenendo flussi di scambio fissi e lo spionaggio industriale da un lato e politico dall’altro permette di avere conoscenze interne all’Europa da poter usare per processi di lobby e politica estera. I dazi imposti dalla amministrazione Trump potrebbero essere un assist al colosso cinese per lo scontro economico in Europa.

Per ottenere quello che vuole la Cina deve evitare che l’Europa parli con “una sola voce” e abusare delle spaccature interne tra i diversi stati portando avanti la sua agenda bilaterale. Avere accesso a virtualmente tutte le comunicazioni in Europa permetterebbe di anticipare potenziali dissidi tra due o più stati europei ed usarlo a proprio vantaggio.

Lo scandalo Huawei in Europa (che ha forzato il MEP a dare l’immunità di 4 parlamentari accusati di corruzione [154][155]) dimostra come la Cina voglia penetrare in profondità partendo proprio dai vertici alti. Ad oggi la Cina si trova davanti un contrasto da parte dell’Europa [156] e il suo supporto sistemico alla Russia in un momento di conflitto non sta di certo aiutando a creare sintonia tra i due mondi [157][158].

Marcando il territorio digitale europeo, la Cina si impostando come una minaccia informatica interessata alle comunicazioni tra i diversi stati per trovare un approccio efficace nella bilancia bilaterale cinese che richiede un mercato di importazione come quello dell’Europa per il sostentamento della sua economia.

Le capacità degli attori cinesi possono minare i processi economici interni all’Europa creando uno svantaggio industriale oltre che politico, in una situazione di incertezza sul futuro dell’Europa il dispiegamento di forze digitali può permettere una penetrazione sul tessuto politico ed economico europeo con conseguenze che non è detto siano congrue agli interessi dell’EU.

Grazie ai contenuti di cui sopra abbiamo compreso l’estrema flessibilità e capacità operative degli attori cinesi, le abilità spannano dalla persistenza al furto di dati in ambienti estremament eterogenei tra di loro. Interessante è la relazione tra gli APT in questione ed il mondo ransomware che risulta essere un ottimo strumento per la copertura delle attività cinesi.

Diversi APT cinesi hanno utilizzato famiglie ransomware per la cifratura delle vittime, dopo aver ottenuto dati e file di interesse il gruppo lanciava questo tipo di malware come “muro di fumo” andando a complicare le fasi di incident response e forensic. Inoltre è oramai chiaro l’approccio “low-and-slow” per lo spionaggio con una persistenza sulle vittime che si estende per mesi e persino anni dall’ingresso iniziale.

Può sembrare contradditorio ma l’utilizzo di un malware rumoroso come il ransomware in campagne state-sponsored è per una motivazione di OPSEC. Se assumiamo le tracce lasciate dagli attaccanti come puntini da collegare per creare un disegno ci sono diversi modi per evitare che il blue team ricostruisca le loro azioni o identità :

Il punto 3 è cruciale per comprende l’uso di ransomware in attività di spionaggio. Una volta ottenuto l’obbiettivo principale (eg:/ spionaggio) l’utilizzo del ransomware permette di avere due vantaggi, (1) l’inquinare evidenze delle operazioni di spionaggio e (2) forza la vittima alle operazioni di salvaguardia e continuità dei processi di business creando confusione sui quali informazioni sono state rubate.

Inoltre usare il brand del ransomware come “maschera” è un ottimo modo per confondere la vittima su quali sia stato il vero impatto nella sua organizzazione, la pressione derivata dal ransomware obbliga le vittime a recuperare il funzionamento delle reti facendo passare in secondo piano la ricostruzione degli attacchi.

Gli APT cinesi hanno compreso che conviene essere rumorosi ma passare come un “semplice” attore motivato dal profitto rispetto all’essere completamente furtivi rischiando di far comprendere alla vittima le loro vere intenzioni.

APT41, oramai punto cardine dello scenario cinese, nei suoi primi interventi nell’industria videoludica ha usato un ransomware non individuato prima (si presume creato da APT41 stesso) chiedendo un riscatto esiguo rispetto al trend globale [159]. Questa tattica è rimasta nel portfolio operativo di DoubleDragon anche in avvenimenti più recenti [160][161].

Dal 2021 anche APT27 si è introdotto in azioni ransomware [162] all’interno di operazioni di cyberspionaggio più ampie con durata di anche anni prima dell’impiego della crittografia.

La vera punta di diamante su questa tecnica di mascheramento è senza dubbio ChamelGang (a.k.a CamoFei) [163][164] che si concentrò su infrastrutture critiche dalla sua scoperta nel 2019, le vittime di ChamelGang includono sia il pubblico che privato con settori analoghi a quelli del FYP in essere. Col tempo CamoFei ha portato maggiore attenzione al settore healthcare senza risparmiare l’uso di ransomware dopo le operazioni di spionaggio [165][166].

Bejing sta settando un nuovo standard nella guerra digitale e nello spionaggio incorporando strumenti del crimine digitale in operazioni allineate con gli interessi statali [167][168][169]. Questa metodologia ci insegna ad avere una chiave di lettura degli attacchi ransomware più sottile dimostrando come strumenti per il crimine da profitto possano essere sostenuti da attori nazionali.

Sommando i diversi aspetti delle minacce digitali cinesi si svela una dimensione offensiva prolifica e sofisticata a livello industriale. La Russia ha sfruttato la sua scena criminale interna per il reclutamento di attori da sfruttare per motivazioni nazionali [170][171], gli APT iraniani e sono legati principalmente ad apparati militari e di sicurezza come IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) [172][173] come anche quelli Nord Coreani [174][175].

La Cina invece riesce a distinguersi anche nella tassonomia dei suoi APT e dei suoi membri. Come esempio iniziale si può prendere il caso I-SOON [176]. I-SOON è un’impresa (privata) cinese che ha avuto forti relazioni con il governo cinese alla quale vendeva buona parte dei suoi prodotti e servizi.

I-SOON ha ricevuto un leak (16 Febbraio 2024) di una lunga serie di documenti, chat ed informazioni interne che ne hanno svelato le attività offerte dalla azienda [177], tra cui servizi APT for hire [178]. In particolar modo le analisi sui contenuti del leak hanno mostrato come I-SOON avesse pubblicizzato software e malware usati da APT41 in campagne precedenti e che avesse una disputa legale con un’altra azienda chiamata Chengdu 404 [179]. Alcuni dipendenti di Chengdu 404 sono stati individuati come operatori di APT41 dall’FBI [180][181] che sottolinea come le operazioni di tali dipendenti siano state fatte nel periodo di assunzione [182].

Oltre agli altri servizi di I-SOON e Chengdu404 (che comprendevano servizi di sorveglianza e controllo di social network cinesi) è chiaro come queste due aziende, entrambe con contratti statali, facessero parte di un network che componeva l’intero apparato che noi identifichiamo come APT41.

Prima di aggiungere altri esempi di aziende che hanno offerto i loro servizi, diventando di fatto armi digitali per il governo cinese, portiamo la nostra attenzione ad alcune analisi fatte da diversi analisti riguardo le operazioni di APT cinesi da alcune fonti citate precedentemente.

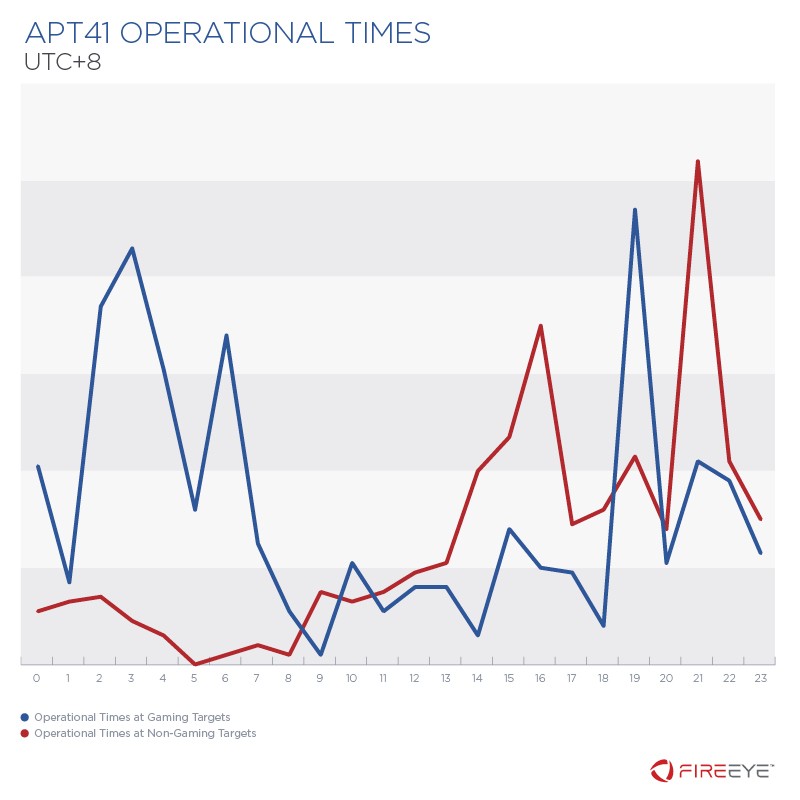

Ancora più interessante il grafico sottostante :

Gli orari operativi di diversi APT coincidono con quelli tipici dei lavoratori cinesi, per quanto riguarda operazioni unicamente per-profit [183] (pubblicizzate in vari forum) invece c’è uno spostamento in orari extra-curriculari notturni.

Il fattore temporale non è da sottovalutare e ci aiuta a dare una forma all’ombra dietro agli APT cinesi mostrando come dietro non ci siano individui “out-of-the-box” ma bensì parte integrate del tessuto tecnico-industriale del paese. Come abbiamo discusso nella prima sezione il governo cinese è presente in diverse forme all’interno delle aziende, in particolare a quelle indicate nei settori chiave.

Questo ecosistema si differenzia molto da altri stati quali Russia, Iran o Nord Korea creando un terreno estremamente fertile non solo per nuovi attori ma anche per le abilità operative sostenute da una forte R&D industriale. Le capacità aziendali si vanno ad unire con gli obbiettivi nazionali con minacce robuste e persistenti.

Altre aziende come Wuhan XRZ (attribuita ad APT31 [184]) ed Integrity Tech (Flax typhoon [185]) seguono lo stesso schema operativo degli esempi precedenti, non c’è da stupirsi se le capacità offensive della Cina sono cresciute di pari passo con la sua economia ed industrializzazione.

Il settore della ricerca di vulnerabilità 0-day è strettamente legato agli attaccanti assunti dal governo cinese [186], gli APT cinesi sono rinomati per l’uso di vulnerabilità 0-day ed ad aiutarli è il governo stesso che obbliga i ricercatori a riportare questo tipo di vulnerabilità unicamente allo stato cinese [187].

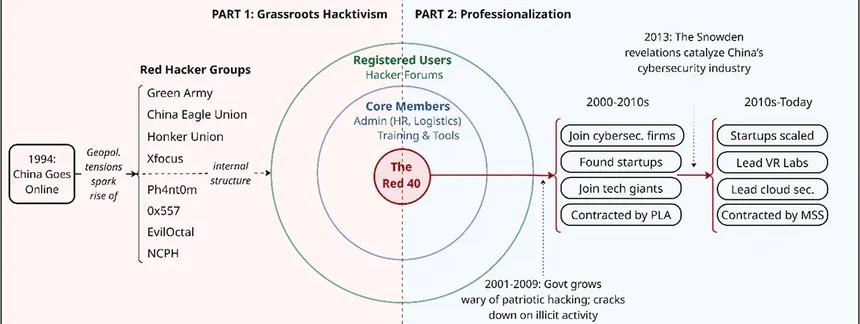

Le origini di questo dinamismo nell’ambiente della sicurezza informatica cinese ha radici negli anni ’90 con il movimento di hacktivisti “Red Hackers” (anche detto “Honkers”) [188][189] che hanno generato ambienti per la crescita di talenti nel settore. Successivamente il cambio nel piano economico e la fusione tra pubblico e privato voluta da Xi Jinping ha permesso di professionalizzare questi individui per la creazione di un’industria che ha poi generato gli APT di qui abbiamo discusso.

L’economia cinese gioca un ruolo chiave per le sue capacità offensive e le politiche di Xi Jinping si muovono verso una indipendenza orientata sul ricircolo domestico per rendersi resilienti verso l’esterno, tutelando le sue industrie e la crescita industriale la Cina sta anche tutelando i suoi APT oramai essenziali per scopi sia militari che di intelligence.

Attualmente la Cina sta puntando sulla crescita di talenti in campo infosec disincentivandoli a partecipare ad eventi stranieri [190] e creando a realtà domestiche per questo tipo di target [191][192]. Le prospettive non sono molto chiare, visto l’opacità verso l’esterno, ma chiaramente la Cina vuole (ed in un certo senso, deve) mantenere la sua posizione attuale nel campo digitale per mantenere il suo status economico e politico verso il futuro.

Nel 2017 Vladimir Putin e Xi Jinping si incontrarono in Kazakhistan con tanto di telecamere e stampa ad attendere la riunione tra i due leader. Il presidente russo si presentò, assieme al suo staff diplomatico, davanti ad un segretario del CCP solitario a causa di un errore logistico che ha ritardato l’arrivo della delegazione cinese al tavolo. Putin per rompere l’imbarazzo nella stanza definisce il suo alleato cinese “один воeц” (in russo “guerriero solitario”) causando una risata complice tra i due [193].

Questa scena è una ottima analogia al comportamento cinese non solo sullo scenario politico internazionale ma anche su quello culturale che bloccano la capacità di comprensione, e quindi di comunicazione, di questa nazione dai principi anziani ma con sviluppi verso la modernità recenti rispetto al resto dell’Asia [194].

Xi Jinping non ha solo cambiato il gioco sul piano politico, economico o sociale ma anche sulla visione culturale che inserisce nel CCP una missione di “salvaguardia della civiltà” da interferenze occidentali [195]. Il segretario generale del CCP ha descritto una perdita di valori culturali ed ideologici nell’occidente assieme ad una deindustrializzazione in sezioni geografiche come l’Europa e USA.

I tumulti che si sono presentati in occidenti hanno permesso alla Cina di perpetuare la loro strategia economica e di influenza mantenendo però una chiusura ed indipendenza che la hanno resa (apparentemente) resiliente alle conseguenze degli scontri geo-politici recenti.

Comprendere la natura ed origine delle operazioni APT cinesi ci permette di avere una visione sulle vere intenzioni di questa nazione, che non riusciamo a comprendere (ne a farci comprendere), andando oltre alle dichiarazioni politiche. La forza digitale cinese viene proiettata all’esterno dei suoi confini con prepotenza solo grazie alla chiusura di questi confini sul piano economico ed informatico creando un ambiente domestico fertile.

Il miglioramento economico del dragone sono state possibili solo grazie all’ottenimento di proprietà intellettuale (di fatto rubata) tramite i propri APT che sono stati oltretutto fondamentali per comprendere quali sono i punti deboli dell’occidente tramite la compromissione di servizi di telecomunicazione.

La fusione tra pubblico e privato, crimine digitale ed attori nazionali oltre a quello cinetico e digitale si sono rivelati un successo per il paese cinese che non è però esente da punti deboli. Nonostante la spinta industriale, la domanda interna cinese rimane sempre insufficiente e se non si presentano opportunità di esportazioni a mercati come quello Europeo rischia di minare la stabilità cinese.

Il piano della economia circolare voluto da Jinping si sta rendendo sempre più complicato perché le chiusure che ha imposto li si stanno ripresentando in un periodo di sbilanciamento interno. L’aumento delle attività APT cinesi in Europa sono da intendersi come un atto di scrutamento e conoscenza per trovare la fessura dalla quale inserirsi, sono azioni che non vanno ad impattare (direttamente) il settore militare o industriale cinese ma quello della politica estera che deve essere efficace in questo momento di bisogno.

Il contributo degli attaccanti digitali del governo cinese ci dimostra come nella sicurezza informatica il tecnicismo deve essere unito alle circostanze ambientali per permettere di comprendere, prevedere e contrastare le minacce future.

Se la comunità infosec si deve interfacciare con quella economico-politica anche l’inverso può far comprendere la direzione di altri paesi che, coma la Cina, rimangono distanti sul piano politico e culturale. Solo il tempo dimostrerà se l’approccio di Xi Jinping ed il suo arsenale informatico riusciranno a coincidere con gli obbiettivi posti dal CCP e a superare gli ostacoli attuali.

La Cina ha deciso la sua direzione ed è chiaro l’interesse nello spionaggio dell’esterno con i suoi APT a farli da spina dorsale. Ad oggi né la politica né l’economia sono esenti dal sottostare al piano digitale essendo quindi esposti alle sue minacce. La protezione da tali attacchi richiede in primis una cultura informatica e conoscenza del concetto di sicurezza (sia nazionale che non) perché se pur vero che molti attori sono semplicemente spinti da motivazioni di profitto altri invece vogliono minare l’economia, struttura politica e società nella quale viviamo.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…