There you have it! On December 20, 1990, something epochal happened at CERN in Geneva.

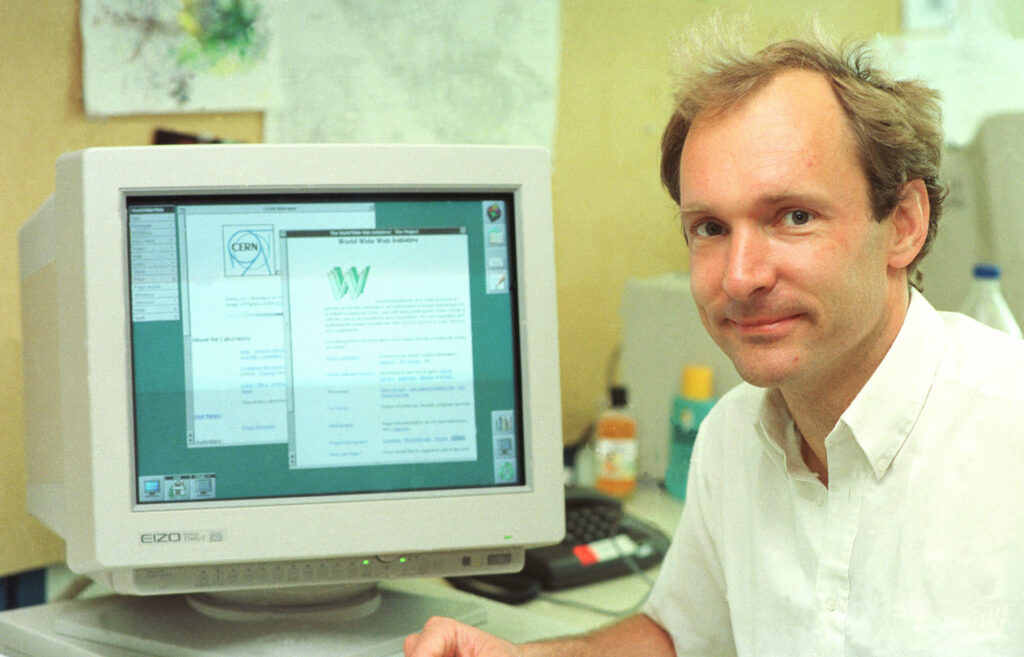

Tim Berners-Lee , a British computer genius, created the first website in history, info.cern.ch , created with the aim of helping scientists share information.

It was an ambitious project, born to make life easier for researchers from around the world. Its goal? To bring together scientists and scholars from different countries and institutions. Initially, only CERN staff were allowed access, but it opened its doors to the general public on August 6, 1991.

It was a historic moment even if many within CERN did not fully understand this innovation!

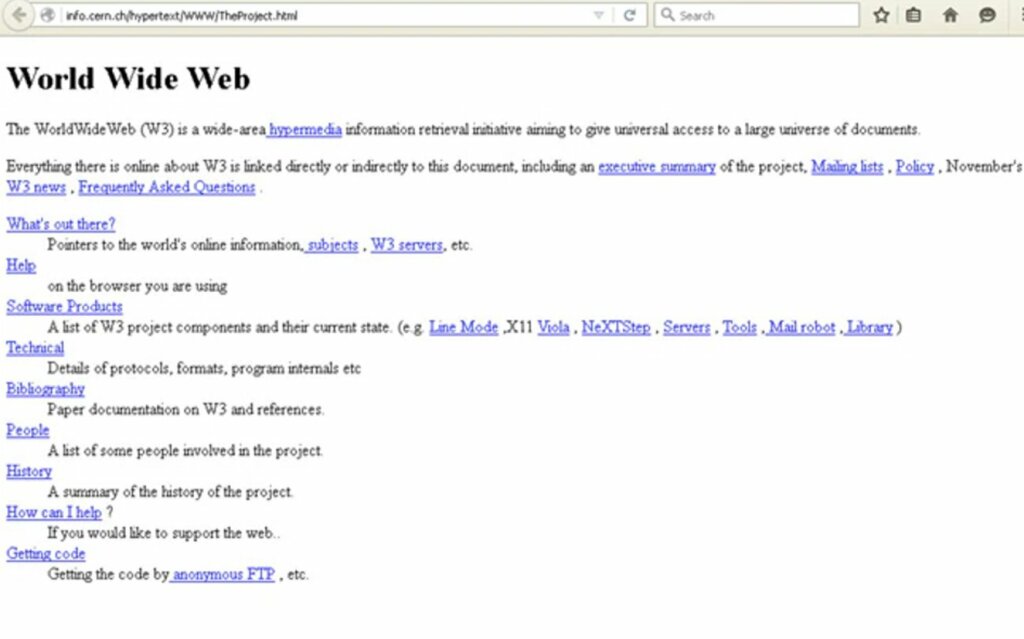

That site was essentially a guide on how to use the World Wide Web. It basically explained how to access remote documents and configure new servers. It was nerdy stuff, but it made history! Today, that site and that machine are collector’s items, a true treasure of the web. And to think it all started with a simple idea: sharing information. What a powerhouse, right?

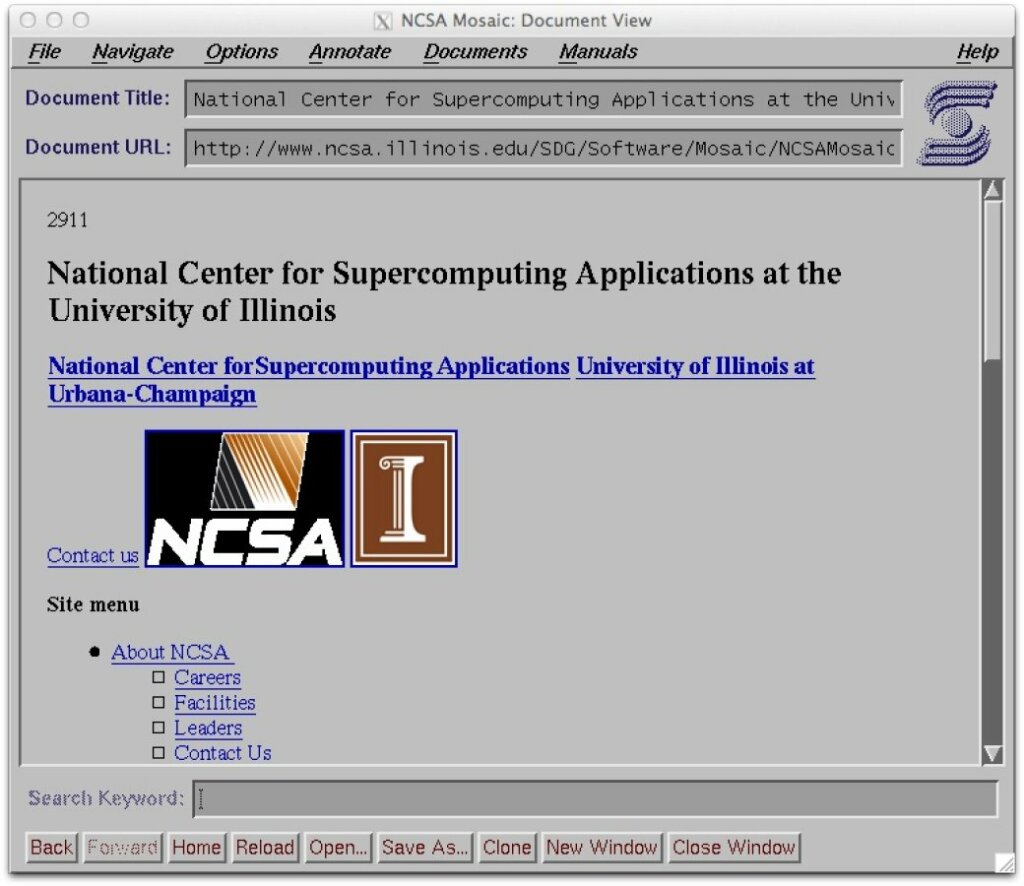

The graphic design reflected the philosophy that guided the project. A light background, dark text, and minimal hyperlinks: no decorative elements, no images. In the original World Wide Web proposal, Berners-Lee had made it clear that the priority was not the graphics, but the universal readability of the text, which was considered essential to ensuring access to the greatest possible number of users.

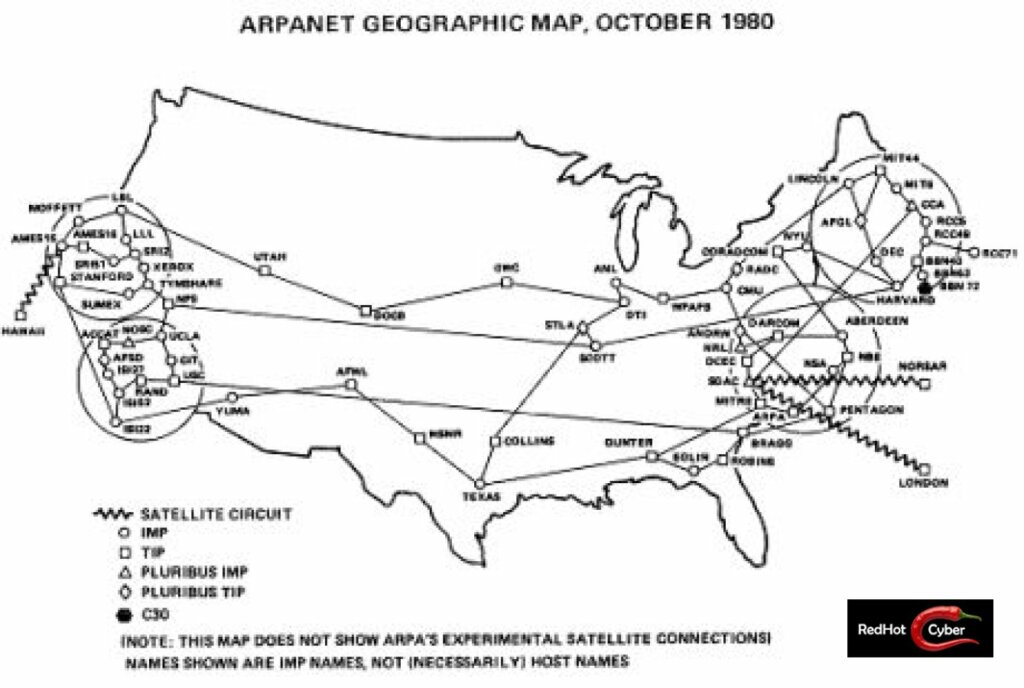

By the late 1980s, the Internet already existed, but it was a tool reserved almost exclusively for academic, military, and scientific contexts.

Information was distributed across heterogeneous and often incompatible systems: mainframes, personal computers, and proprietary networks . All of this was complex! Since there was no standard, this prevented smooth and flexible data exchange.

At CERN this problem was particularly evident.

Thousands of researchers produced and consulted technical documentation, but the content was often confined to specific machines or required dedicated software to be read. There were partial solutions, such as ARPANET or Usenet , and structured navigation systems like Gopher, developed by the University of Minnesota, but a truly universal model for document access was still lacking.

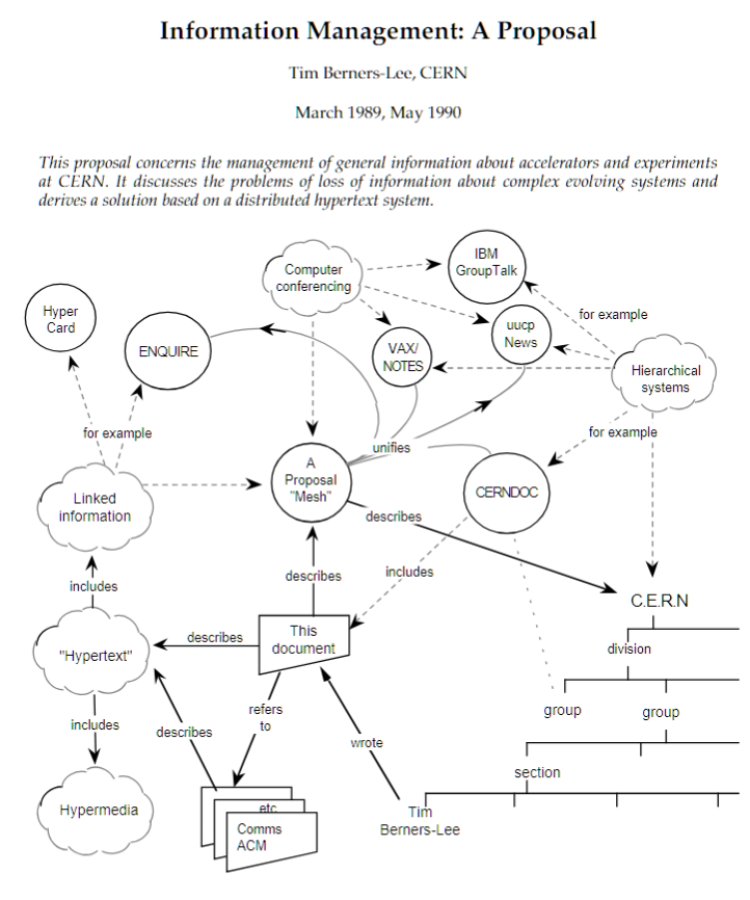

Berners-Lee’s 1989 proposal, entitled “ Information Management,” started with a simple idea: connecting documents distributed across different computers through a network of hyperlinks. Between 1990 and the end of that year, this vision took concrete form thanks to the development of three fundamental elements.

Berners Lee proposed three solutions:

These technologies, which are still the basis of online browsing today, were developed on a NeXT computer, a workstation produced by the company founded by Steve Jobs after leaving Apple. On that machine, Berners-Lee also created the first browser in history, initially called WorldWideWeb and later renamed Nexus.

The original browser had a feature that has almost disappeared today: it was not only used to view pages, but also allowed you to edit them and create new ones .

The emerging concept of the Web was that of an interactive environment, where users had the opportunity to actively participate in the creation of content. However, with the advent of commercial interests, this initial vision of the Web was gradually abandoned, as business took over.

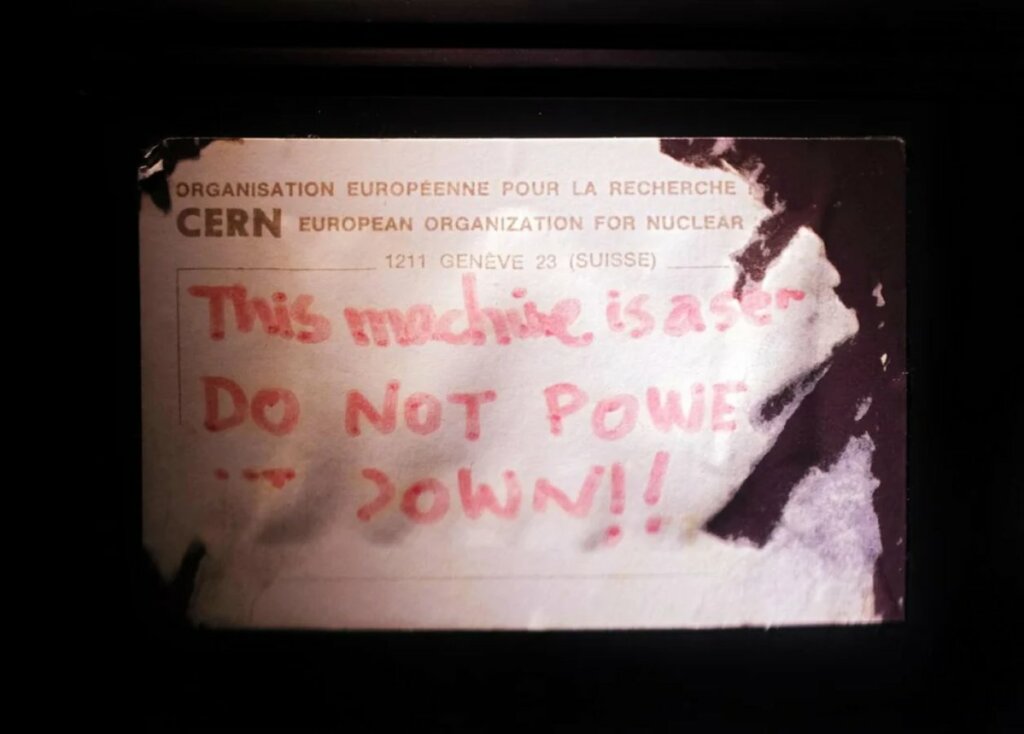

The NeXT computer itself also served as the world’s first web server . To prevent accidental shutdowns, a handwritten warning was affixed to the machine , explicitly warning against disconnecting its power, as doing so would render the entire World Wide Web unreachable.

For some years the Web remained a tool used mainly by physicists and researchers.

The turning point came on April 30, 1993, when CERN decided to make the World Wide Web a public domain technology , renouncing any rights to commercial exploitation. This decision prevented the emergence of monopolies and favored the free dissemination of standards.

Around the same time, the first graphical browsers aimed at a wider audience appeared. Among these, Mosaic , developed in 1993 by the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois, introduced the ability to display images embedded in text, transforming the Web into a more accessible and visually engaging environment.

Today the Web has billions of pages and hundreds of millions of domains, but its origins remain tied to that set of essential documents published at CERN, as well as to some intuitions that came a few years earlier from the technological prodigy Douglas Engelbart (the inventor of hypertext and the mouse).

By the 1990s, technology was ready for all of this, and the first significant services and sites began to appear: in 1993, Aliweb was born, considered the first search engine, while in 1994, organizations like Amnesty International and companies like Pizza Hut launched their first online presences.

In 2013, CERN restored the original address of the first website, making it accessible again in a simplified version. This archive represents not only a historical document, but also a tangible testimony to the beginning of a technological transformation that has redefined the way humanity produces, shares, and accesses information.

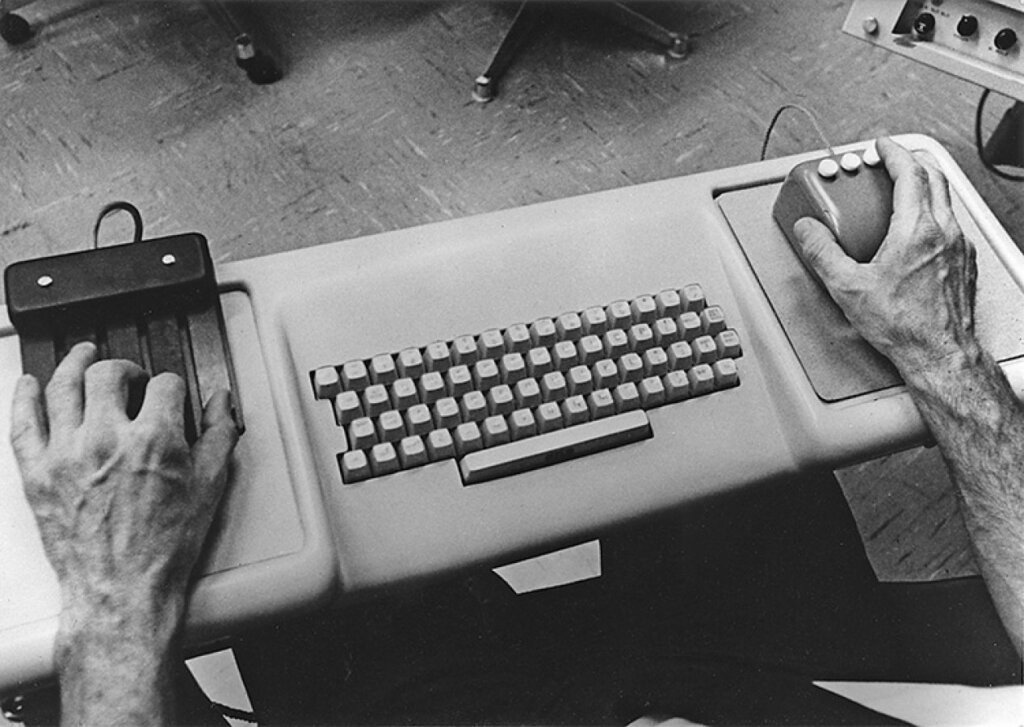

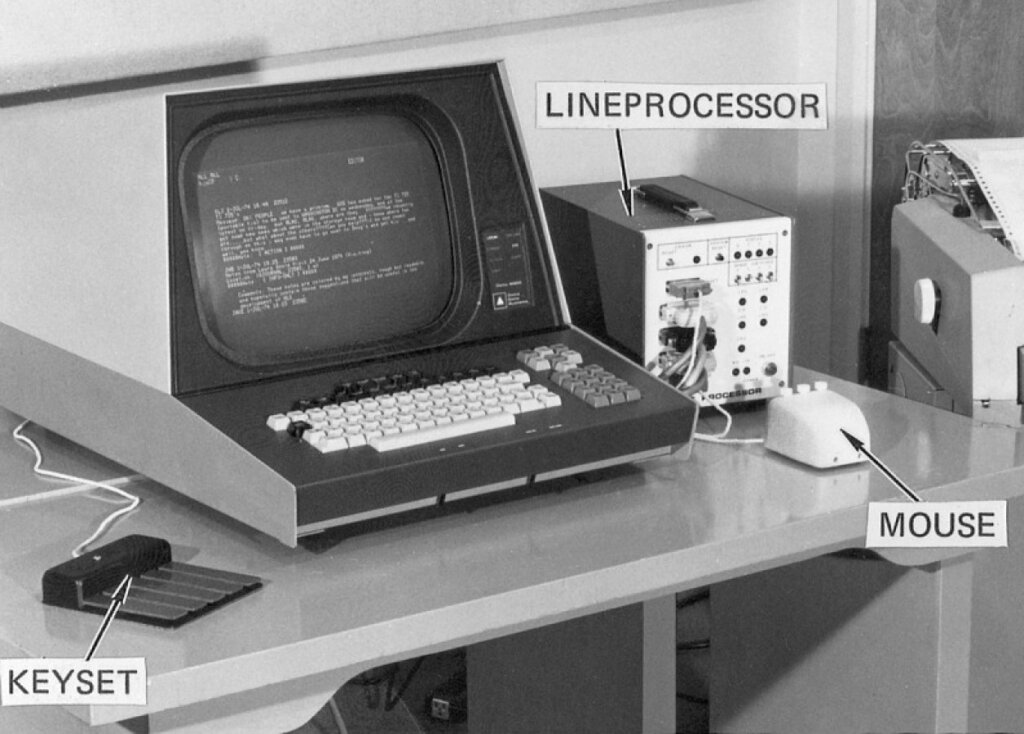

The conceptual foundations of the World Wide Web date back well before Tim Berners-Lee’s work at CERN. A key milestone dates back to December 9, 1968, when Douglas Engelbart presented the famous “Mother of All Demos” in San Francisco. In that public demonstration, Engelbart showcased a radically new vision of computing, centered on human-machine interaction and the possibility of using computers as tools to amplify collective intelligence.

During that demonstration, Engelbart introduced his oN-Line System (NLS), a work environment that integrated then-revolutionary features: hyperlinks between documents, real-time collaborative editing, nonlinear information navigation, on-screen windows, and remote communication. Concepts that seem obvious today were presented when computers were still closed instruments, used primarily for calculations and reserved for a few specialists.

Engelbart’s genius wasn’t limited to technical intuition. His greatest strength lay in his ability to imagine a complex, open, and interconnected system, one that necessarily required the contribution of a community of engineers, researchers, and developers to become reality. The ideas showcased in the Mother of All Demos weren’t finished products, but operational visions that paved the way for decades of collective work to translate them into concrete, scalable, and widely usable technologies.

Tim Berners-Lee’s contribution fits into this perspective. Between the late 1980s and early 1990s , he successfully implemented many of those insights, adapting them to a global network like the Internet. The World Wide Web can be seen as the pragmatic synthesis of those pioneering ideas: hypertext, associative navigation, and distributed access to information, transformed into simple, open, and universal standards. This historical continuity directly connects Engelbart’s vision to the Web we know today.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.