In recent months, two seemingly unrelated events have highlighted an uncomfortable truth: Europe no longer controls its own digital infrastructure . And this dependence, in an increasingly tense geopolitical landscape, is not only an economic risk, but a systemic vulnerability.

The first alarm bells rang when Microsoft suddenly disabled Azure access for the Israeli intelligence unit . This was Unit 8200, previously accused of spying on Palestinians in Israeli-controlled territories using Microsoft technology. No warning, no graduality: a switch flipped , revealing just how much decision-making power over critical infrastructure rests in the hands of a few global corporations.

The second episode, even more emblematic, is from today, concerning the recent dispute between X (Elon Musk’s platform) and the European Commission . After a €120 million fine for violating European regulations, X is not having it and has deleted the Commission’s advertising account, accusing it of having improperly used the platform’s tools . Brussels defended itself by recalling that it had suspended all forms of advertising on X for months and that it had only used the tools made available.

Beyond the dynamics between multinationals and institutions, the message is clear: the EU’s ability to communicate on social media, inform citizens, and implement digital policies is subordinated to the commercial will of non-European companies over which it has no control.

These episodes demonstrate a key point: those who control technology also control the behavior, communication, and even politics of nations . Europe discovered this late, having for years believed that digital globalization was synonymous with neutrality.

But talking about proprietary technology means dealing with a very different reality:

And above all, it means accepting that no country is truly sovereign if it depends on others for cloud services, operating systems, chips, and critical digital infrastructure .

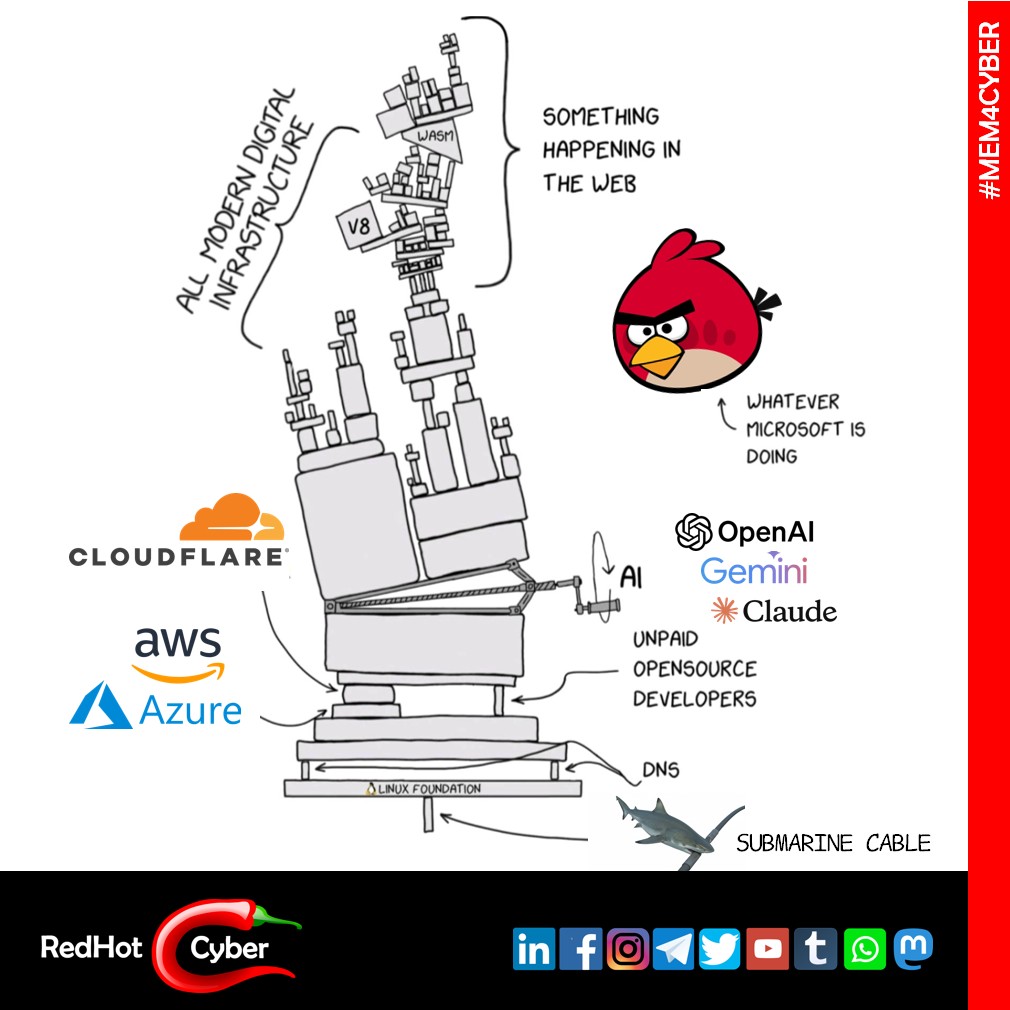

In today’s hyperconnected world, every technological incident has immediate and global effects. We saw this recently with the outages at AWS , Azure , and Cloudflare ( the first incident and the second incident ) that paralyzed public services, businesses, banks, newspapers, mobility, and healthcare across half the world. These are no longer “technical problems,” but real systemic risks .

Europe, lacking a comprehensive technology stack of its own, lives in a state of total dependence. We are a highly digitalized continent that rests… on foundations built elsewhere .

Asserting technological sovereignty doesn’t mean rejecting the cloud; on the contrary, it means building our own .

A European cloud, based on European hardware, European operating systems, European hypervisors, and European software. A complete supply chain, from hardware to application.

How long does it take? 20 years!

A long, complex, and costly process. But today it’s more necessary than weapons development. Because these are the weapons of the future, the “economic” weapons, and they can be deployed with a single click.

And above all, a political choice is needed: to plan this path for 20-30 years , not for a single legislature.

Because in the current geopolitical chessboard, whoever controls technology controls economies, defenses, and democracies.

And today Europe controls none of this.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.