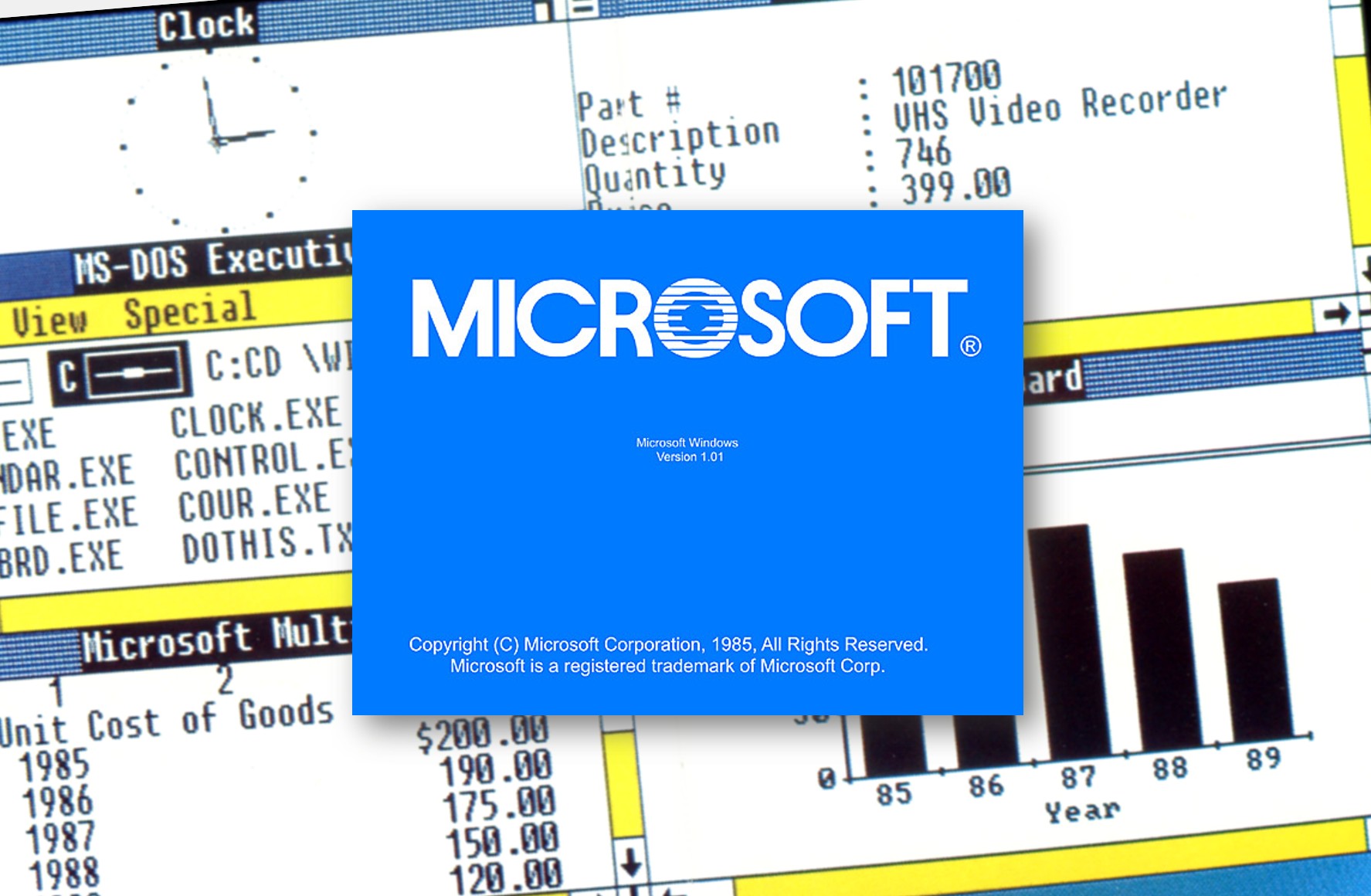

Exactly 40 years ago, on November 20, 1985, Microsoft released Windows 1.0 , the first version of Windows, which attempted to transform the then-personal computer from a machine with a monotonous command line into a system with windows, icons, and mouse control .

This is the groundbreaking of some of the greatest innovations of our time, conceived by the genius of Douglas Engelbart and the “oN-Line System” , the system designed in the sixties that introduced a window operating system connected to a mouse, presented in the historic “mother of all demos” of December 9, 1968.

To today’s audiences, this may seem obvious (or unfamiliar), but in the mid-1980s, the very idea of a graphical user interface on the mass-market IBM PC was practically revolutionary.

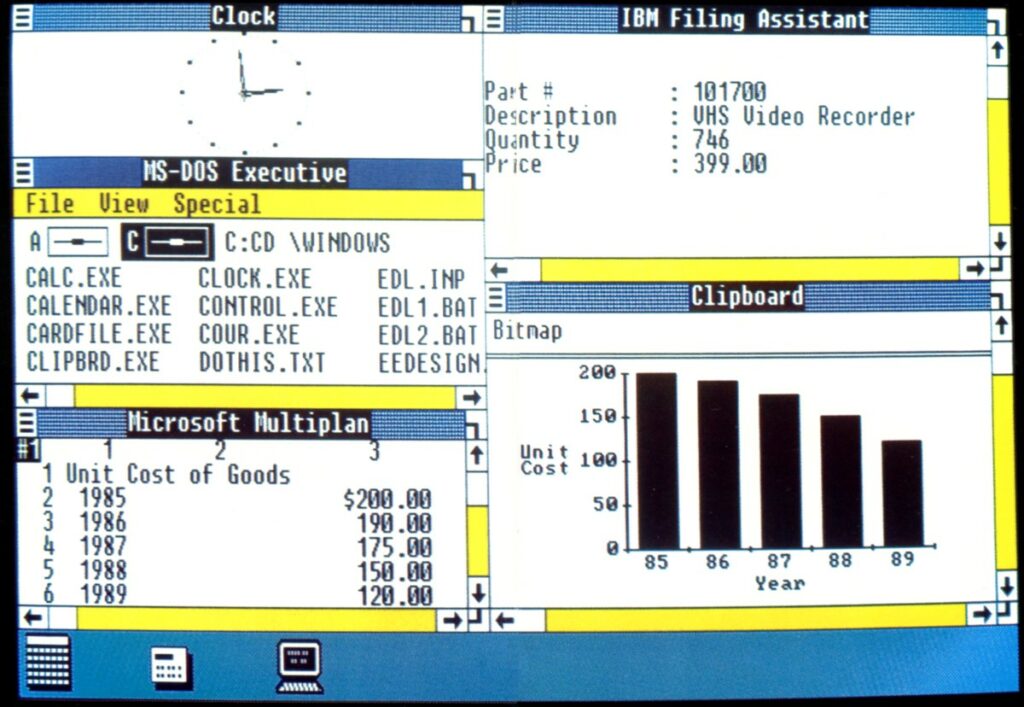

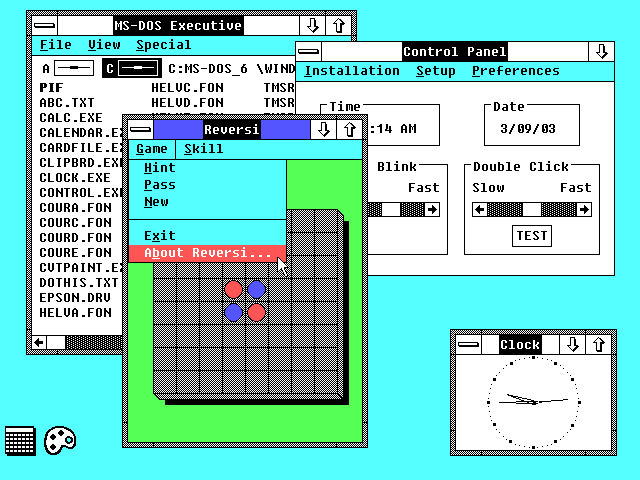

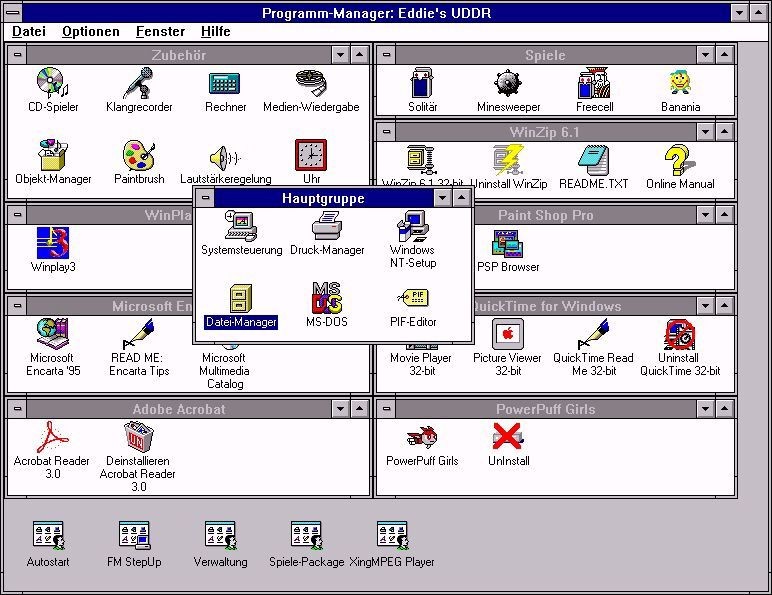

Technically, Windows 1.0 wasn’t a full-fledged operating system. It was a graphical overlay on top of MS-DOS, a 16-bit shell called MS-DOS Executive that overlaid the existing system and allowed programs to run in windowed mode.

The first version was released only in the United States; updates and international editions followed later, and the package cost around $99, a considerable sum at the time.

The interface was unusual even by 1980s standards. In Windows 1.0, windows couldn’t be freely overlapped; they were strictly tiled on the screen. The user controlled the system primarily with the mouse, selecting menu items and dragging elements, although the menus themselves worked strangely and required holding down the mouse button .

But even then, Microsoft was already defining the principles that would later evolve into the desktop model we know.

Windows 1.0 included a suite of applications that are still surprisingly recognizable today. Users were offered Paintbrush , the ancestor of today’s Paint , Notepad , the Write text editor, Calculator , a clock , a terminal , the Cardfile card database, the clipboard, and a print manager. These applications allowed users to take simple notes, draw simple graphs, print documents, and run multiple programs simultaneously, albeit with very limited multitasking.

Hardware requirements at the time of release were considered quite high. Running Windows 1.0 required an Intel 8086 or 8088 processor, at least 256 kilobytes of RAM, a graphics card, and two double-sided floppy disk drives or a hard drive. Many reviewers complained of noticeable system slowdown when running multiple applications, especially if the computer had less than the recommended 512 kilobytes of memory. By comparison, the current minimum of 4 gigabytes for Windows 11 seems almost like a leap forward.

Windows 1.0 received a lukewarm reception from the market. Critics noted its slow interface, poor compatibility with existing DOS programs, and the limited number of applications written specifically for Windows. Compared to Apple’s existing graphics systems, Microsoft’s product seemed rudimentary, and some reviewers compared its performance on a PC with 512 kilobytes of RAM to “molasses spilled in the Arctic,” alluding to its incredibly slow performance.

However, Microsoft didn’t abandon the idea. Within a couple of years, the company released several updates to Windows 1.x with support for new hardware and European keyboard layouts, before introducing Windows 2.0 and the particularly successful Windows 3.0.

These releases alone made the IBM PC graphical interface a de facto industry standard and laid the foundation for the vast software ecosystem we have become accustomed to by the 1990s.

Today, Windows 1.0 has long since become a museum relic: emulators of the system are released out of nostalgia and curiosity, and Microsoft itself occasionally remembers its early graphical interface through Easter eggs and themed projects, such as the amusing Windows 1.11 app based on the TV series Stranger Things .

But many ideas and even some programs from that era have survived to this day, and the 40th anniversary reminds us how rapidly both computers and our understanding of what an intuitive interface should be have changed in just a generation.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.