There are books that explain technology and books that make you understand why you should pause for a minute before scrolling through a feed. Il Futuro Prossimo , Sandro Sana ‘s new work, available on Amazon , belongs to the second category: it doesn’t pretend to educate you, it pretends to make you think. And it does so without technicalities, without barriers, and without that distance that information technology often creates between the writer and the reader.

Sandro Sana is a well-known figure in the world of Italian cybersecurity (CISO and director of the Cyber division of Eurosystem , teacher, communicator, member of the Scientific Committee of the National Cyber 4.0 Competence Center , member of the DarkLab Group and editorialist for Red Hot Cyber ) but here he deliberately sets aside the posture of the technician to adopt that of the lucid narrator.

He doesn’t sacrifice his trademark precision, but delivers it in a human, conversational, and direct manner. The result is a book that, while addressing risks, algorithms, and artificial intelligence, can also be read on the couch, in the evening, after a normal day.

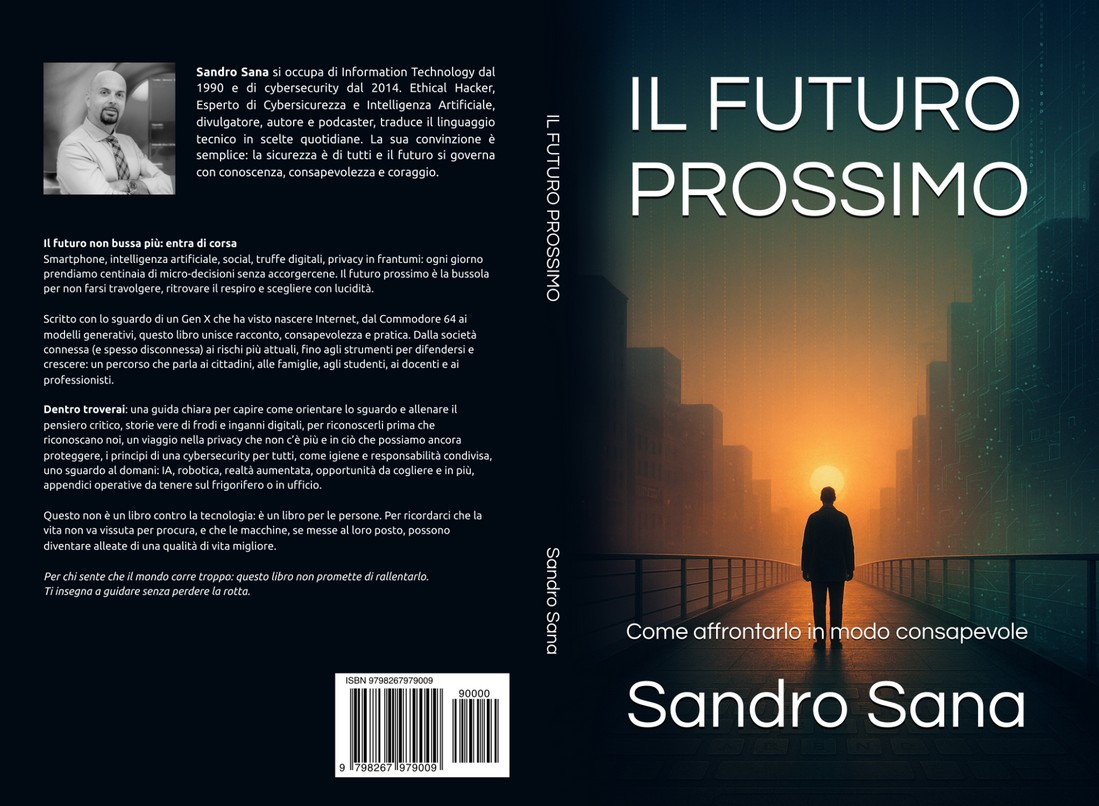

At a certain point, while leafing through the book, you get the feeling you’re not just reading an essay, but a true declaration of civic responsibility. This is clearly evident from what the author chose to put on the back cover, a sort of emotional compass for those preparing to tackle these pages:

The future no longer knocks: it rushes in. Smartphones, artificial intelligence, social media, digital scams, shattered privacy: every day we make hundreds of micro-decisions without realizing it. The near future is the compass that keeps us from being overwhelmed, allows us to breathe again, and makes clear-headed choices.

Written through the eyes of a Gen Xer who witnessed the birth of the Internet, from the Commodore 64 to generative models, this book combines storytelling, awareness, and practice.

This isn’t a book against technology: it’s a book for people. To remind us that life shouldn’t be lived vicariously, and that machines, if put in their place, can become allies for a better quality of life.

These lines are not just an editorial presentation: they are the book’s mission.

Reading them, one immediately understands that The Near Future does not want to “scare”, it does not want to “educate” from the height of the pulpit, it does not want yet another rhetoric against social media or AI.

It wants to restore measure, awareness, rhythm .

He wants to put the person back at the centre.

The book’s strength lies in its narrative continuity: Sana doesn’t begin with risks or AI, but with personal history and cultural roots. The reader immediately enters a generational debate that highlights an acceleration that everyone can sense, but few have had the courage to say so openly:

“If my grandfather had a lifetime to get used to electricity and my father decades to embrace television and the automobile, if I’ve had years to digest the arrival of the computer and the Internet, how many hours will my children have to understand the impact of artificial intelligence on their lives? ”

It is one of the most powerful passages in the entire volume: the idea that the time for human adaptation has shrunk to the blink of an eye, while complexity grows exponentially.

From here, the storytelling takes on an almost cinematic form. The Prologue takes us back to the 1980s, to an era when the digital world was a game of cassette tapes and waiting, but also of wonder and initial questions:

“When I first came into contact with a Commodore 64 in the 1980s (…) that little computer was opening the doors to a new world. It was a bridge between fun and discovery.”

It is within these roots that the tone of the entire book is built: a gaze that remembers, observes, compares, and then guides the reader into what digital has become today.

The journey continues with a tale of a digital society that doesn’t judge or condemn, but rather organizes what we all feel: attraction and struggle, power and fragility. Sana describes our time as a beautiful house made of glass, where connection is both a privilege and a pressure:

“Digital society is our home. Wonderful view, transparent walls. But there are windows to clean and curtains to draw. (…) If we learn to name things well, we will also return to living them well.”

It’s a subtle but powerful invitation: to be present, not simply connected, and to understand that digital education isn’t about “knowing how to use,” but about “knowing how to choose.”

The narration then touches on the theme of privacy and does so with a style that mixes daily observation and awareness:

“Every gesture leaves a crumb, and the crumbs become traces, the traces profiles, the profiles predictions. (…) It’s not a blatant theft, it’s a silent move.”

It’s one of the most successful sentences in the entire book, because it says exactly what we all feel, even without finding the words to explain it: the sensation of being “moved sideways” within our own data.

The section on artificial intelligence is a turning point in the reading. There’s no apocalyptic tone, no slogans. There are questions, doubts, and responsibilities.

Sana gets to the heart of the matter with a clarity that leaves no shortcuts:

“AI won’t just steal our jobs: it risks stealing parts of us. (…) Preparing for the future means learning new skills and preserving our humanity.”

The framework is not technical, but existential: the real risk is not losing a job, but losing the ability to choose, discern, and interpret, and this makes the chapter, although anchored to real issues, one of the most human in the entire book.

The book’s ending is a gesture of healing. It doesn’t propose miraculous solutions or political agendas: it closes with a simple, almost domestic scene that becomes a symbol of the entire journey undertaken.

“The future isn’t a sprint, it’s an agreement to be renewed every day between digital and real. (…) As long as there’s someone who pauses for a second before sharing, there’s hope.”

It is an image that remains within and is perhaps the clearest sign that this book does not want to indoctrinate, but rather to keep open a possibility : to regain masters of our time, our choices and our gaze.

Because The Near Future is a book that only apparently talks about technology. In reality, it’s about identity, memory, attention, relationships, and responsibility. It’s a book that helps us understand not “how digital works,” but how we function within digital .

It’s accessible, honest, written in a tone that doesn’t distance but invites closeness, and above all: it’s a book that doesn’t tell you what to think, but allows you to do it better.

Anyone living in the connected world, that is, everyone, can find something that resembles them.

And this, in the age of the algorithm, is perhaps the rarest gift.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.