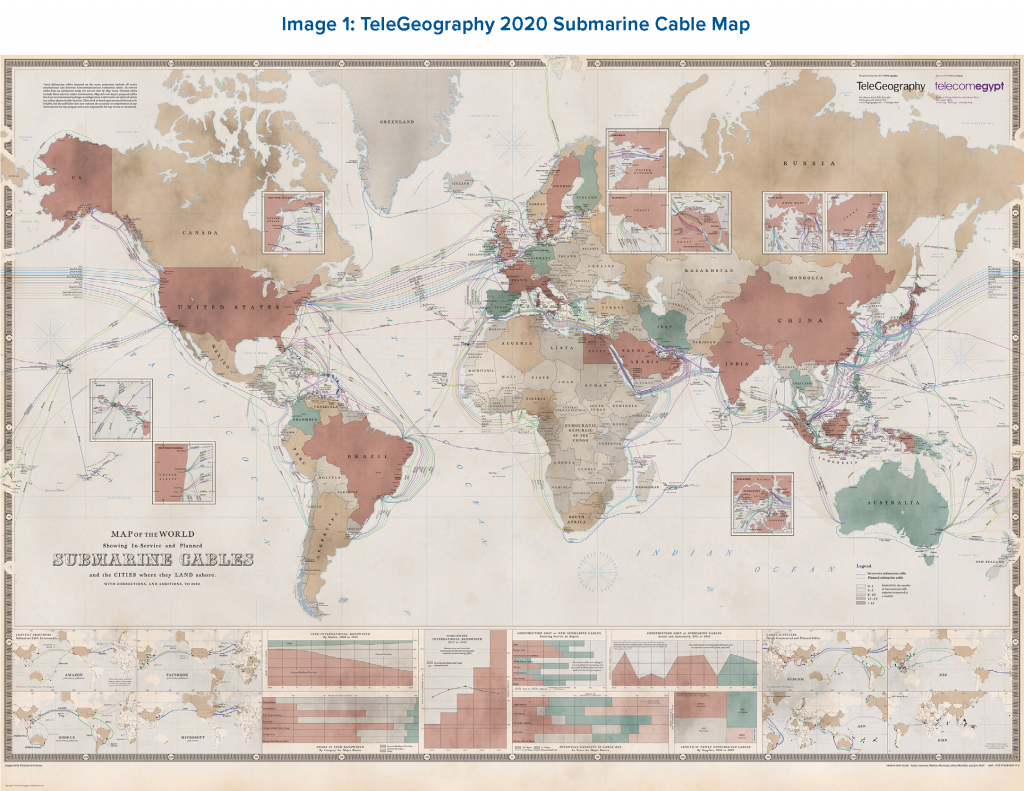

Author: 5ar0m4n Publishing Date: 11/7/2021 We have often addressed the topic of undersea cables on RHC where we talked about the first submarine cable in history and the last one laid in water. But this time we want to tell you about the strategic importance in modern geopolitics of these ocean ridges, where 95% of the world’s Internet communications pass. It seems difficult to understand, but the vast majority of intercontinental global Internet traffic, over 95%, travels on submarine cables that cross the ocean floor. These hundreds of cables, owned by private and government entities, support everything from consumer shopping to government document sharing to scientific research to the next virtual reality. The security and resilience of undersea cables and the data and services that travel through them is an often overlooked element of modern geopolitics, and the construction of new undersea cables is a critical part of the ever-evolving “physical topology” of the Internet around the world.  The 2020 Cable Map Has Landed

The 2020 Cable Map Has Landed

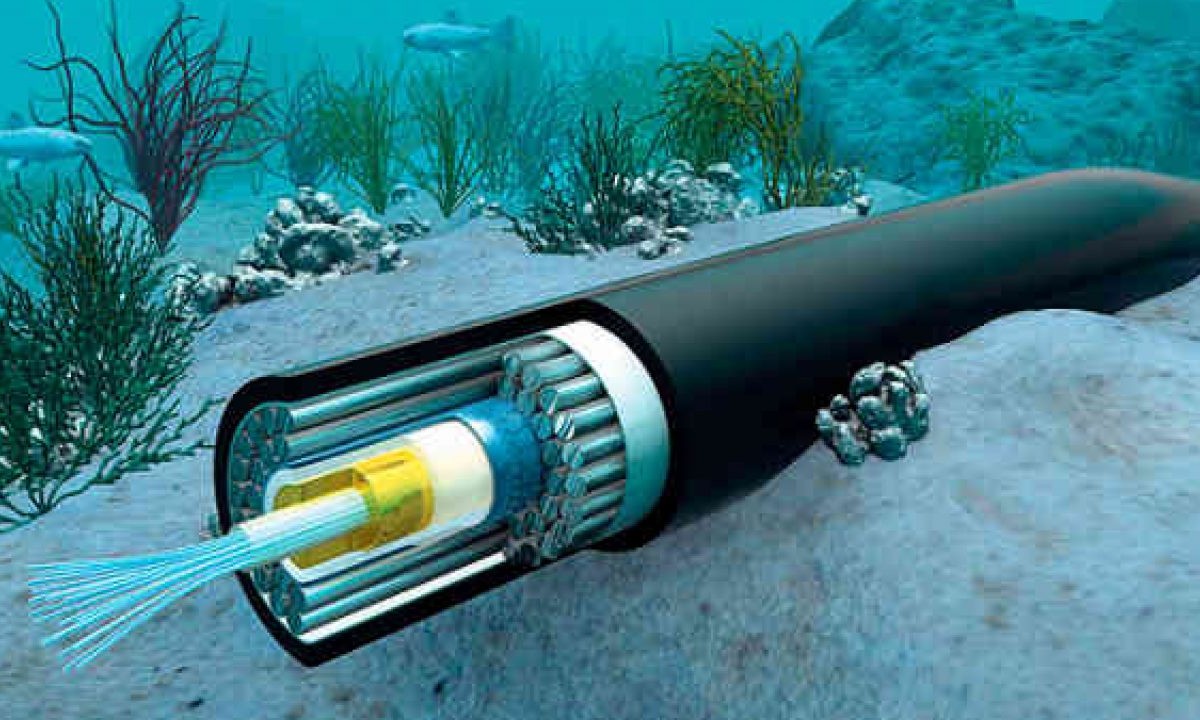

Submarine cables range in thickness from about 1 cm to about 20 cm in diameter, with the cost proportional to the cross-section. The cables can be made in many ways, but most consist of a central fiber element, buffered in gel or petroleum jelly; then any copper wire needed to transmit power to repeaters and branch units; layers of armor; and finally an outer membrane intended to prevent the intrusion of seawater and plants and animals. It is only the very thin internal fiber that transmits the Internet data through the cable, be it email, video, or sensitive documents, and such fiber optic cables are faster and cheaper than satellite communications.  These cables are laid on the ocean floor to connect countries, such as South America and Europe. Each submarine cable also has at least two “landing points,” which are the locations where the cable meets the shore. The structures at these landing points can provide multiple functions, including terminating an international cable, providing power to the cable, and acting as a national and/or international connection point. The owner of an undersea cable may not be the same entity as the owner of the landing station.

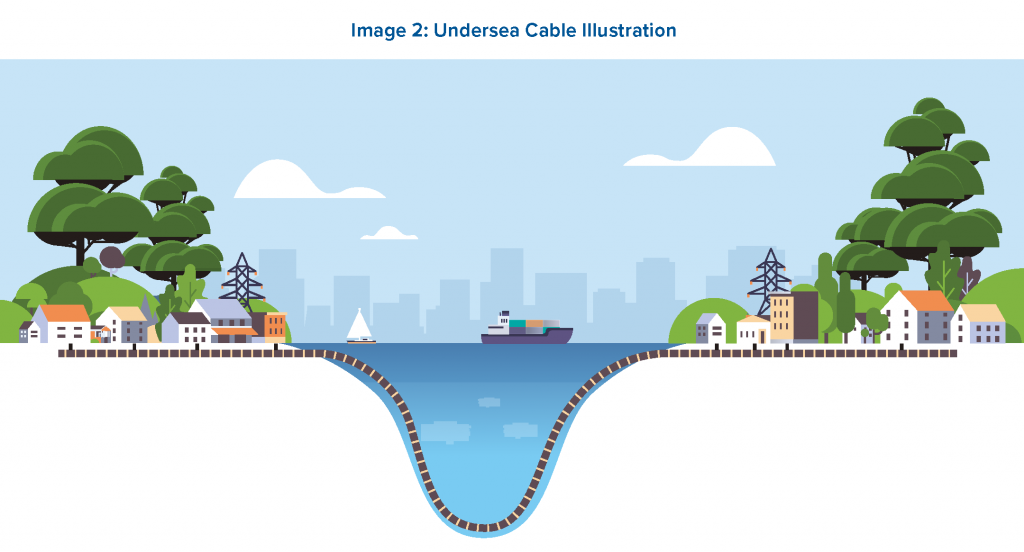

These cables are laid on the ocean floor to connect countries, such as South America and Europe. Each submarine cable also has at least two “landing points,” which are the locations where the cable meets the shore. The structures at these landing points can provide multiple functions, including terminating an international cable, providing power to the cable, and acting as a national and/or international connection point. The owner of an undersea cable may not be the same entity as the owner of the landing station.  The two landing sites and their stations

The two landing sites and their stations

Undersea cables have been in use around the world for decades and decades. The first undersea cables were used in 1820 by an attaché at the Russian embassy in Munich to send electrical telegraph communications. This submarine cable technology evolved with more sophisticated telegraph communications in the mid- to late-1800s (with the first transatlantic submarine telegraph cable in 1858, which we covered in an article on RHC), then with voice communications in the early- to mid-1900s, and fiber optic data transmission in the mid- to late-1900s. Submarine cable lines were also linked to European imperial expansion and colonialism, which were thought to allow for broader boundaries of global empire. Today, these cables transmit previously unimaginable volumes and types of data, from business communications and scientific research to personal messages and military records, implementing security (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) and resilience (the degree to which data can be restored or restarted in the event of damage or disruption) that are a critical part of protecting the global Internet in the twenty-first century.

Damaging these cables is one way to disrupt Internet communications. Despite all the intangible images of the Internet such as the “cloud,” “cyberspace,” the Internet still relies on “physical” things to function, and those physical objects, including cables, can be destroyed.  Repairing an Undersea Cable In 2008, a ship attempting to dock off the coast of Egypt accidentally severed an undersea cable, leaving seventy-five million people in the Middle East and India with limited access to the Internet. In 2015, the Yemeni government cut off internet connectivity in the country, a crackdown that was aided by the country having only two undersea cables connecting it to the rest of the world. Natural weather events such as undersea earthquakes can also damage cables and temporarily reduce internet availability across an entire region. Ensuring that undersea cables, which help route data in the event of a failure and are quickly restored if damaged or interrupted, are resilient is a critical element in ensuring the resilience of global internet traffic and the social functions that depend on it. That’s not to say that a single damaged cable will bring down the internet globally, as the internet is designed to work around the failure and data can be sent via other routes, although this may significantly reduce internet connectivity for a country or region. There are also not many publicly documented examples of governments destroying or damaging cables, although there is much national security concern about the potentially serious consequences if governments choose to pursue such ends (e.g., in a war scenario.

Repairing an Undersea Cable In 2008, a ship attempting to dock off the coast of Egypt accidentally severed an undersea cable, leaving seventy-five million people in the Middle East and India with limited access to the Internet. In 2015, the Yemeni government cut off internet connectivity in the country, a crackdown that was aided by the country having only two undersea cables connecting it to the rest of the world. Natural weather events such as undersea earthquakes can also damage cables and temporarily reduce internet availability across an entire region. Ensuring that undersea cables, which help route data in the event of a failure and are quickly restored if damaged or interrupted, are resilient is a critical element in ensuring the resilience of global internet traffic and the social functions that depend on it. That’s not to say that a single damaged cable will bring down the internet globally, as the internet is designed to work around the failure and data can be sent via other routes, although this may significantly reduce internet connectivity for a country or region. There are also not many publicly documented examples of governments destroying or damaging cables, although there is much national security concern about the potentially serious consequences if governments choose to pursue such ends (e.g., in a war scenario.

Three trends are increasing the security and resilience risks of submarine cables. First, authoritarian governments, especially in Beijing, are reshaping the physical layout of the Internet through companies that control the Internet infrastructure, to route data more favorably, gain better control of Internet blockades, and potentially benefit from espionage. Second, more companies that operate submarine cables are using network management systems to centralize control of components, such as ROADM reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers and robotic patch bays in remote network operations centers, which introduces new layers of security risk. operational.  Third, the explosive growth of cloud computing has increased the volume and sensitivity of the data traveling through these cables.

Third, the explosive growth of cloud computing has increased the volume and sensitivity of the data traveling through these cables.

For nation states, tapping into cables carrying information around the world is an attractive espionage opportunity. In the late nineteenth century, British intelligence used its access to an international telegraph cable hub in the small village of Porthcurno to gain an edge in eavesdropping. In the 1970s, the US National Security Agency deployed submarines and divers to attach recording devices to a vulnerable cable on the Russia’s eastern coast that carried sensitive Russian military communications. Today, a similar phenomenon occurs with undersea cables that carry Internet traffic: they are a potential goldmine of information for governments. When Russia illegally annexed Crimea in 2014, the Russian military targeted the undersea cables connecting the peninsula and the mainland to gain control of the information environment. The Russian government widely recognizes the strategic value of physical Internet infrastructure. In December 2019, Taiwan alleged that Beijing was supporting private investment in undersea cables in the Pacific as a mechanism for spying and stealing data. But ensuring the resilience of undersea cables, especially for key choke points in the global network, is geopolitically important because even slow repairs to key cables can slow down the distribution of traffic across land masses. Recall also that the DataGate scandal, initiated by American whistleblower Edward Snowden, brought to light a Five Eyes system called “Tempora” used for spying through submarine cables. In October 2013, it became known that the European chancelleries of France, Germany and Italy, and in general of 32 world leaders, were spied on through these programs. In particular, Italy was spied on not only by the NSA but also by the British using this system. Therefore, the owners of the cables could insert backdoors or otherwise monitor the landing stations. Likewise, cable builders could compromise the security of the physical infrastructure along the ocean floor.

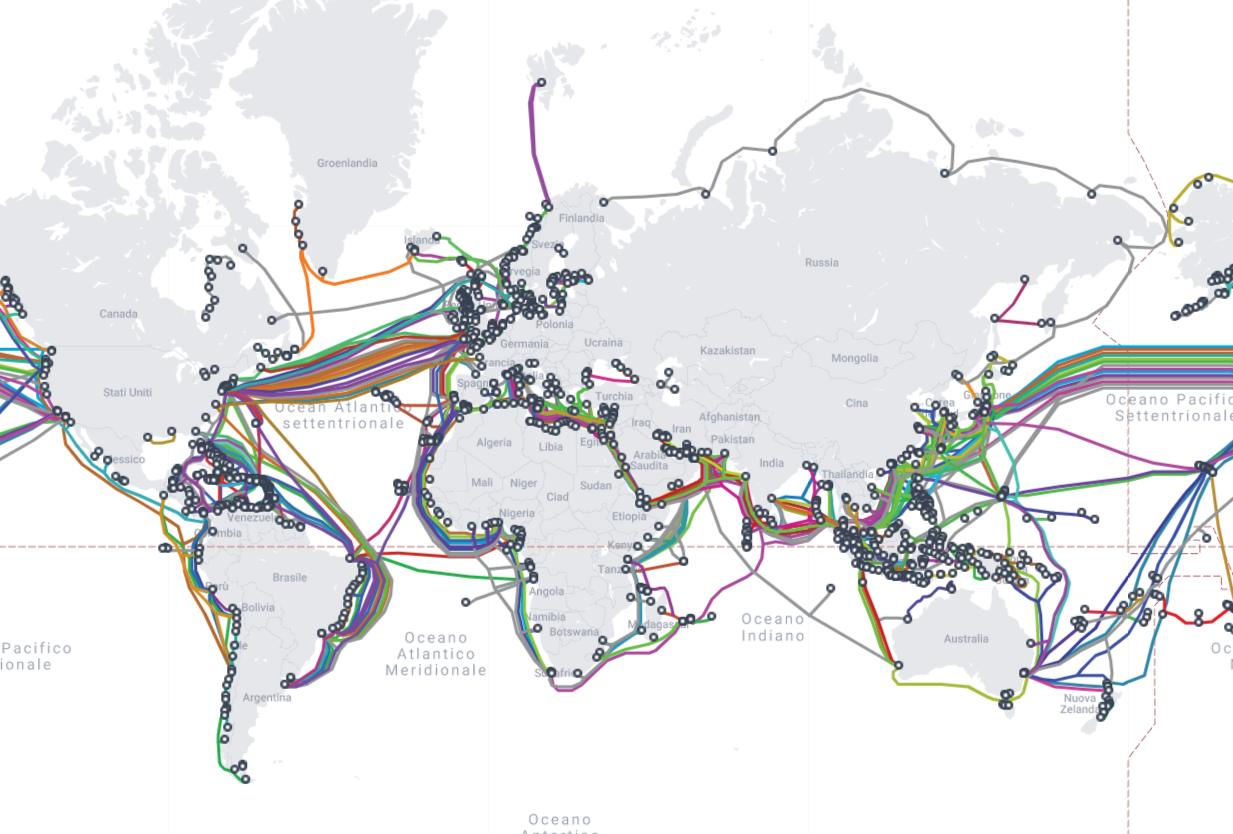

There are approximately 475 submarine cables distributed around the world, as reported by the Submarine Cable Map website by TeleGeography, encoded with additional data collected from open sources by 383 different entities (private companies and state-controlled entities). The first observation from this data is that cable development, globally, is increasing. In 2016, fifteen new cables were ready for service around the world world. Twenty-eight new cables went into service around the world in 2020, nearly doubling in just four years. This increase is no accident: there are several drivers at play. More traffic is being sent across the global Internet every year. Other countries are also looking to expand Internet penetration within their own borders as well as expand bandwidth. Cloud service providers are increasingly involved in directing the construction of the physical infrastructure to support their data storage and routing services. And generally, Internet companies can also profit from long-term cable investments by using this physical infrastructure to move their data across the global Internet more quickly. This global Internet infrastructure has long been developed by an international consortium of companies. A single cable may have multiple corporate owners, often each embedded in different countries. This consortium approach to building and maintaining cables is driven by a variety of factors, including the financial costs and complex logistics of laying cables on the ocean floor, the number of shorelines these cables may touch (and, therefore, the number of the need for a company at the other end to operate a landing point), and the profit those companies can generate from carrying traffic over the cable.

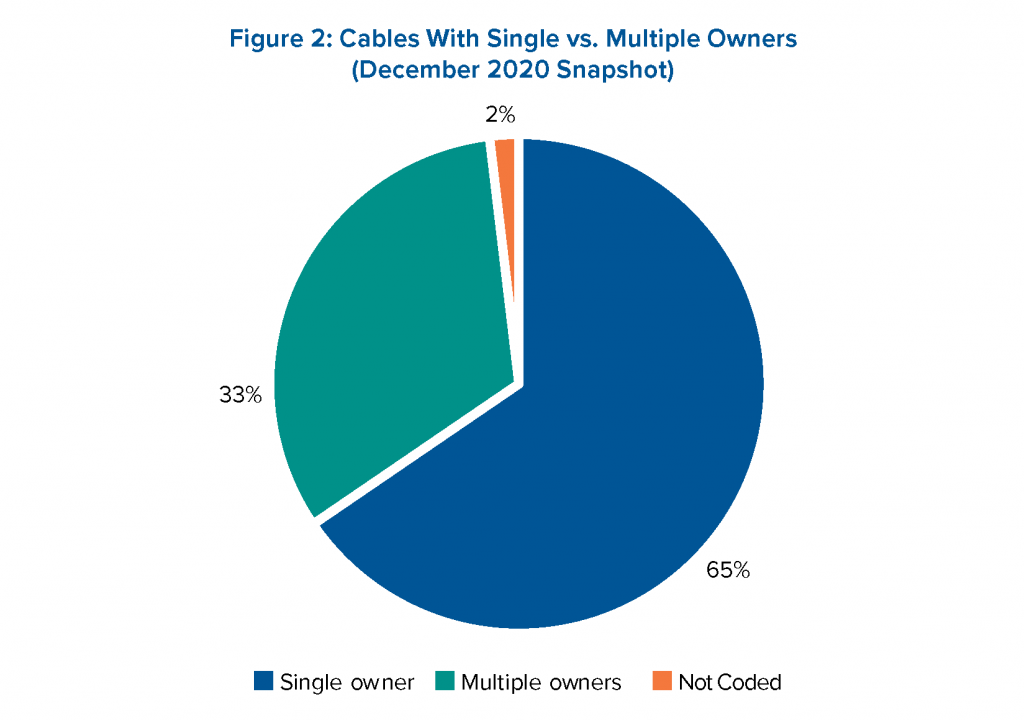

Mapping the ownership landscape of submarine cables is critical to understanding what levers of control can be applied by private companies, state-owned companies and governments. While some parts of the Internet’s physical and digital infrastructure are operated by a few major private sector companies, these cables are diverse. The majority of submarine cables deployed worldwide, 65% as of December 2020, have a single owner. Only a third of cables deployed have multiple owners. Seventy-two cables have only two owners, twenty-one cables have only three owners and fifteen have four owners. However, in some cases these numbers are higher: four cables each have eighteen owners in different countries and the highest number of owners for any single cable is fifty-three: the 39,000 km SeaMeWe-3 cable installed in September 1999. For example, the Europe India Gateway Cable, a 15,000 km cable that went into operation in February 2011, connects eleven different countries and has sixteen different co-owners, ranging from AT&T (US) to Djibouti Telecom (Djibouti) to Airtel (India) to Vodafone (UK). The Japan-Guam-Australia South Cable System, for a recent example, went into operation in March 2020, connects Australia and the US, and is owned by Google (US), RTI Cables (US), and Australia’s Academic and Research Network.  Source: Data from TeleGeography’s Submarine Cable Map website Cables with multiple owners are often the most expensive to build and maintain, such as those that connect multiple countries and have the most bandwidth. Such consortia may also involve a state-controlled company. Distinctive ownership is important from a safety and resilience perspective because it can lead to disparate control over cables, can lead to a situation where multiple governments have legal oversight of companies involved in building and/or maintaining a single cable, and can make it more difficult to determine which entities have control over a cable and to what extent this creates risks to the infrastructure.

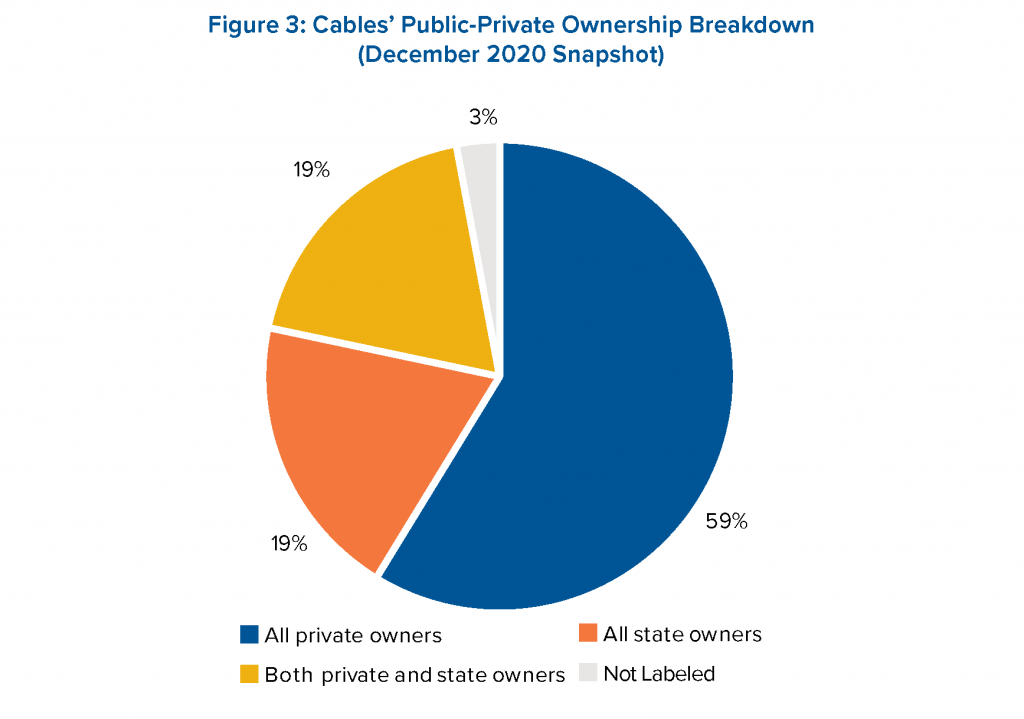

Source: Data from TeleGeography’s Submarine Cable Map website Cables with multiple owners are often the most expensive to build and maintain, such as those that connect multiple countries and have the most bandwidth. Such consortia may also involve a state-controlled company. Distinctive ownership is important from a safety and resilience perspective because it can lead to disparate control over cables, can lead to a situation where multiple governments have legal oversight of companies involved in building and/or maintaining a single cable, and can make it more difficult to determine which entities have control over a cable and to what extent this creates risks to the infrastructure.  The majority (59%) of global submarine cables deployed as of December 2020, or 279 of 475 cables, have only private owners. The global private sector is therefore influential not only on the digital rules of the Internet, but also on its changing physical form. In contrast, only 19% of all cables deployed worldwide, or 93 of 475, are wholly owned by state-controlled entities (i.e., directly owned by a government or through a subsidiary). Of course, private enterprise ownership does not mean that a government cannot directly or indirectly exercise control over the cable. For example, the US government, like most others, has a long history of tapping into private sector-controlled Internet infrastructure for espionage purposes.

The majority (59%) of global submarine cables deployed as of December 2020, or 279 of 475 cables, have only private owners. The global private sector is therefore influential not only on the digital rules of the Internet, but also on its changing physical form. In contrast, only 19% of all cables deployed worldwide, or 93 of 475, are wholly owned by state-controlled entities (i.e., directly owned by a government or through a subsidiary). Of course, private enterprise ownership does not mean that a government cannot directly or indirectly exercise control over the cable. For example, the US government, like most others, has a long history of tapping into private sector-controlled Internet infrastructure for espionage purposes.

The US government, in June 2020, recommended that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) refuse to the license for the Pacific Light Cable Network (PLCN), an undersea cable involving Google, Facebook, a New Jersey-based telecommunications company, and a Hong Kong-based telecommunications company owned by a Chinese firm, because its routing of U.S. data through Hong Kong would pose a national security risk. One of the DOJ’s specific concerns is that Beijing has used the Chinese owner of the Hong Kong branch to access US individuals’ data, stating: “the current national security environment, including the PRC government-backed efforts to acquire sensitive data of millions of US individuals” as well as the cable project’s “connections to the PRC state-owned carrier China Unicom” are reasons to block the cable’s development. In other words, the US government has highlighted the risk of Chinese state influence on two fronts: compromising cable data via cable owners (e.g., harvesting intelligence via a state-controlled landing point) and changing the physical form of the Internet to route more global traffic through China (e.g., creating multiple choke points in the global network under Chinese government control). These risks are distinct but related, as the underlying actions may be carried out by the same entity. The DOJ is not alone in its concerns about Chinese government control over cable owners. In November 2019, CNN reported on an internal Philippine government report that the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, partly owned by a Chinese state-owned power company, was actually “under the full control” of the Chinese government and vulnerable to disruptions. The reports focused on the Philippine power grid, but the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines is also the sole owner of an undersea cable in the Philippines, making the Chinese state-owned company a co-owner. If these disruption concerns apply to the power grid, there are related questions to be asked about Beijing’s influence over the undersea cable as well. In December 2020, Taiwan accused the Chinese government of backing cable investments in the Pacific Rim as a means to spy on foreign countries and steal data; a spokesperson for Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs told Newsweek that Beijing wanted to “monopolize” Pacific information. These accusations come as state-controlled Chinese entities are taking increasing ownership stakes in undersea cables.

Sources https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/cyber-defense-across-the-ocean-floor-the-geopolitics-of-submarine-cable-security/ https://www.dvidshub.net/news/265680/seabed-space-us-navy-information-warfare-enriches-cyber-resiliency-strategic-competitionhttps://www.submarinecablemap.com/

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.