Il significato di “hacker” ha origini profonde. Deriva dall’inglese «to hack», che significa sminuzzare, intaccare, colpire o tagliare. È un’immagine potente, quella di un contadino che con la sua rude zappa rompe le zolle di terreno, svelando ciò che si cela sotto la superficie. Allo stesso modo, un hacker riesce ad esplorare i meandri più oscuri, sfidandone i limiti e portando alla luce potenti innovazioni, come prima non erano mai state viste.

Ma chi sono davvero gli hacker?

In questo articolo esploreremo la figura dell’hacker da ogni angolazione. Vedremo chi sono, quali sono le loro motivazioni e il loro ruolo nel mondo digitale di oggi. Scopriremo il loro impatto sulla sicurezza informatica, distinguendo tra chi lavora per costruire un ambiente digitale più sicuro e chi lo minaccia.

Il termine “hacker” evoca immagini di figure enigmatiche. Talvolta sono idolatrati come innovatori geniali, altre volte demonizzati come minacce digitali. Questo dualismo riflette la complessità di chi possiede una conoscenza profonda in un campo e una straordinaria capacità di pensiero laterale. Questa abilità permette di risolvere problemi con prospettive nuove e non convenzionali.

La differenza cruciale è nelle intenzioni. Alcuni hacker usano le loro competenze per proteggere, migliorare e innovare. Altri le sfruttano per distruggere, rubare o sabotare. Come la fisica, che può illuminare con l’energia nucleare o devastare con una bomba atomica, l’hacking è uno strumento potente e neutrale. Il suo impatto dipende esclusivamente dall’uso che se ne fa.

L’hacking non è limitato al mondo digitale. È un’arte che attraversa ogni disciplina umana. Quando una persona supera i limiti del conosciuto e rompe le convenzioni con ingegno e creatività, incarna il vero spirito dell’hacking. Diventa un innovatore nel suo ambito.

Essere hacker significa sfidare lo status quo. Significa cercare soluzioni dove gli altri vedono problemi. È una “capacità” che spinge a superare barriere, creando nuove possibilità. Ed è proprio questa visione che, nel bene o nel male, ha il potere di cambiare il mondo.

E ha da sempre cambiato il mondo.

L’hacking è quindi una forma di pensiero che trascende i confini tradizionali. E’ l’arte di reinventare, di scoprire nuove vie dove altri vedono barriere insormontabili. In matematica, può significare trovare una dimostrazione elegante per un problema complesso. In fisica, scoprire applicazioni impreviste di leggi conosciute. In politica, ridefinire il concetto di partecipazione o governance. Persino nella musica, l’hacking si manifesta nella sperimentazione di nuovi suoni e tecniche compositive.

Questa capacità di rompere gli schemi rende l’hacking una forza trasversale, in grado di applicarsi ovunque ci siano regole, strutture o sistemi. È un motore di progresso, ma anche una lente critica che permette di mettere in discussione ciò che è dato per scontato. Quando le convenzioni diventano vincoli, l’hacking le sfida, aprendo la strada all’innovazione.

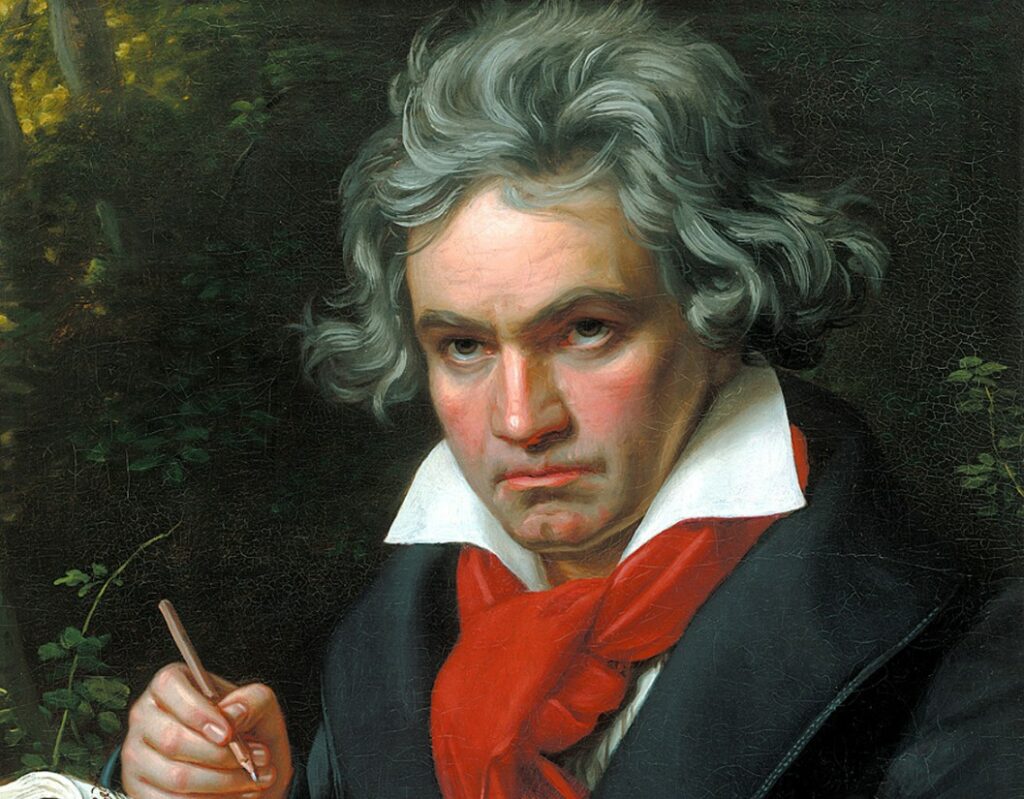

Un esempio straordinario di hacking nel mondo della musica è Ludwig van Beethoven, che infranse ogni regola e creò composizioni che il mondo non aveva mai sentito prima. La sua Nona Sinfonia, scritta quando era completamente sordo, rappresenta una delle più grandi opere musicali della storia. Beethoven ha “hackerato” il linguaggio musicale, superando i limiti imposti dalla sua condizione fisica e reinventando la struttura stessa della sinfonia. La sua capacità di creare qualcosa di assolutamente nuovo, partendo da un contesto di difficoltà estrema, lo consacra come un autentico hacker dell’arte.

Nel mondo della politica, un grande esempio di hacking a fin di bene è Mihail Sergeevič Gorbačëv, l’ultimo leader dell’Unione Sovietica. Gorbačëv “hackerò” il rigido sistema politico sovietico attraverso le sue riforme radicali, come la glasnost (trasparenza) e la perestrojka (ristrutturazione). Questi cambiamenti destabilizzarono il comunismo dall’interno, portando maggiore apertura e modernizzazione in un sistema noto per la sua chiusura e rigidità. La sua visione rivoluzionaria contribuì alla fine della Guerra Fredda, dimostrando come l’hacking politico possa trasformare radicalmente il corso della storia.

L’hacking, tuttavia, non è sempre a fin di bene. Adolf Hitler è un esempio di come questa capacità possa essere utilizzata in modo distruttivo. Hitler sfruttò abilmente le debolezze del sistema democratico della Repubblica di Weimar, manipolando la propaganda, il controllo dell’informazione e la paura per consolidare il suo potere. Come un hacker che trova una falla in un sistema, Hitler identificò e sfruttò le vulnerabilità sociali e istituzionali del suo tempo, trasformando la democrazia in una dittatura totalitaria con conseguenze devastanti.

La capacità di “hackerare” va oltre la tecnologia: si manifesta ovunque ci sia un sistema, una regola o una convenzione da superare. Matematici che rivoluzionano teoremi, fisici che ridefiniscono le leggi dell’universo, artisti che creano nuovi linguaggi espressivi: tutti questi individui sono, a modo loro, hacker.

Ma come ogni grande capacità, l’hacking porta con sé un rischio intrinseco. È uno strumento neutrale, che può essere utilizzato per costruire o distruggere, per innovare o manipolare. Comprendere questa duplicità è fondamentale per riconoscere il valore dell’hacking in tutte le sue forme e affrontare le sfide che esso comporta.

Alla base dell’hacking c’è spesso una motivazione pura e intrinseca: la curiosità.

Gli hacker sono spinti dalla voglia di esplorare sistemi complessi, scoprire come funzionano e individuare modi per superarli o migliorarli. Come abbiamo visto all’inizio, un contadino munito della propria “potente zappa” cerca di rivoltare il terreno, così gli hacker cercano di comprendere le cose dall’interno per poi migliorarle e superarle. Per molti, è una forma di sfida intellettuale che stimola l’ingegno e permette di acquisire competenze tecniche avanzate.

Questa curiosità è molto legata, anche se none esclusivamente, all’amore per la tecnologia. Gli hacker più appassionati vedono il codice come un linguaggio universale e i sistemi informatici come puzzle da risolvere. Per loro, il confine tra gioco e lavoro è sottile: l’hacking diventa un’arte e un modo per esprimere la propria creatività. Un grande hacker, Richard Stallman disse “Fare giocosamente qualcosa di difficile, che sia utile o no, questo è hacking”.

Un tratto comune tra molti hacker è il pensiero laterale, una modalità di ragionamento che li porta a risolvere problemi in modi non convenzionali. Questo approccio li aiuta a generare innovazione, spesso trovando soluzioni uniche e inaspettate. Superare ostacoli tecnologici, esplorare nuove frontiere e rompere le regole è il motore che spinge molti hacker ad eccellere nel loro campo.

Un altro aspetto rilevante riguarda l’affinità tra hacking e la sindrome di Asperger, un disturbo dello spettro autistico che porta a una concentrazione intensa su attività specifiche. Gli hacker, spesso afflitti da questa sindrome, tendono a focalizzarsi in modo esclusivo sul computer e sui sistemi informatici, dedicando ore, giorni e a volte settimane alla risoluzione di problemi complessi. Questo comportamento li rende particolarmente abili nel risolvere enigmi tecnici e nel comprendere in profondità come funzionano i sistemi, spingendoli a creare soluzioni innovative.

La parola “hacker” è spesso fraintesa, associata esclusivamente ad attività illecite o malevole. In realtà, il concetto di hacking nasce come una capacità, una dimostrazione di ingegno e intelligenza per superare ostacoli o innovare in modo creativo. Questa abilità può essere utilizzata sia per scopi costruttivi che distruttivi, ma alla base vi è sempre l’arte di esplorare, comprendere e migliorare i sistemi, sfruttandone al massimo il potenziale.

La cultura hacker ha origine all’interno del Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) del MIT, un laboratorio di studenti appassionati di modellismo ferroviario. Qui, negli anni ’50, figure come Peter Samson, Jack Dennis e Alan Kotok (membri del TMRC) si divertivano a modificare e migliorare il complesso sistema di trenini elettrici, sperimentando nuovi metodi per controllare i loro movimenti. Nel gergo del club, il termine “hack” indicava una soluzione ingegnosa per superare un problema tecnico o migliorare un sistema.

Con l’arrivo dei computer nel campus, questi stessi membri spostarono la loro curiosità e abilità verso i calcolatori. I pionieri dell’hacking iniziarono a esplorare i computer non per distruggerli, ma per comprenderli meglio, spingendoli oltre i limiti per sperimentare nuove possibilità. Tra questi, spicca il nome di Richard Greenblatt, considerato uno dei primi hacker della storia, che contribuì alla creazione di programmi complessi e innovativi.

Il movimento hacker non si fermò ai trenini o ai calcolatori. Con il lavoro di figure come il professor John McCarthy, al MIT, si aprì una nuova frontiera: l’intelligenza artificiale. McCarthy, uno tra i padri dell’IA, dimostrò come il pensiero innovativo degli hacker potesse essere applicato per sviluppare sistemi capaci di simulare il ragionamento umano.

Oggi, il mito dell’hacker affonda le sue radici in questa cultura di esplorazione e sperimentazione. Il termine non definisce un criminale, ma una mente brillante, capace di affrontare problemi complessi con soluzioni intelligenti. Tuttavia, come ogni capacità, l’hacking può essere usato per scopi diversi: c’è chi utilizza queste competenze per proteggere sistemi e costruire innovazioni tecnologiche, e chi le impiega per violare, sottrarre o distruggere.

Questa duplicità è ciò che rende il mondo degli hacker così affascinante e, allo stesso tempo, controverso.

La storia degli hacker è strettamente legata a questa dualità, richiamando l’antica filosofia dello yin e yang. Il bene e il male si intrecciano e formano un uroboro, il serpente che si morde la coda, simbolo dell’eterno ciclo di creazione e distruzione. Il bene non può esistere senza il male e viceversa: ogni progresso nella sicurezza informatica nasce spesso in risposta a una minaccia, così come ogni attacco sofisticato stimola lo sviluppo di nuove tecnologie difensive.

Dagli albori dell’era digitale, la figura dell’hacker ha incarnato questa ambivalenza. Nei primi anni ’60 e ’70, gli hacker erano spesso studenti o ricercatori universitari che sperimentavano con i computer per migliorarne le funzionalità (come visto nel Tech Model Railroad Club nel capitolo precedente). Le loro azioni erano mosse dalla curiosità, dall’innovazione e dal desiderio di condividere conoscenza. Tuttavia, con l’evolversi della tecnologia, alcuni iniziarono a sfruttare le proprie capacità per scopi personali, dando origine al lato oscuro dell’hacking.

Gli hacker sono divisi in diverse categorie, ognuna con una propensione distinta verso la legalità e l’etica delle loro azioni. Da un lato, ci sono gli hacker etici, che lavorano per proteggere le aziende e i governi da attacchi informatici, e dall’altro, gli hacker criminali che sfruttano le stesse competenze per ottenere vantaggi illeciti.

Tra questi, esiste una figura intermedia: gli hacker gray hat, che camminano sul filo del rasoio, utilizzando il loro ingegno per individuare falle nei sistemi, ma talvolta infrangendo leggi o violando confini etici.

Gli hacker rappresentano una delle figure più affascinanti e controverse dell’era digitale. Le loro azioni possono essere guidate da una molteplicità di motivazioni, che spaziano dalla pura curiosità e passione per la tecnologia a fini economici, politici o ideologici. Comprendere cosa spinge gli hacker a entrare in azione è fondamentale per delineare le diverse sfaccettature di questo universo.

Non tutti gli hacker si limitano alla curiosità o alla sperimentazione: alcuni agiscono mossi da motivazioni economiche, ed è quì che nasce il “crimine informatico”. Questo sottogruppo si suddivide in individui singoli o gruppi altamente organizzati, spesso strutturati come aziende clandestine.

I cybercriminali da profitto mirano a sfruttare vulnerabilità nei sistemi per estorcere denaro o rubare dati. Tra i gruppi più noti ci sono LockBit, Qilin e Stormous. Questi gruppi sono famosi per attacchi mirati contro aziende, istituzioni e infrastrutture critiche. Operano con un modello di business chiaro, spesso utilizzando il sistema Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS). Questo permette anche a criminali meno esperti di entrare nel crimine informatico e estorcere denaro.

Le loro motivazioni sono economiche. La promessa di guadagni rapidi, supportata dall’anonimato del dark web e delle criptovalute, li rende una minaccia crescente. Il loro motto è: minore sforzo, massima resa.

Un’altra categoria significativa è quella degli hacker di Stato (Spesso anche chiamati come gruppi APT o meglio Advanced Persistent Threat). Sono individui o gruppi che operano per conto di governi per perseguire obiettivi strategici. Questi hacker sono strumenti di potere geopolitico, utilizzati per il furto di proprietà intellettuale, il sabotaggio di infrastrutture critiche o il condizionamento dell’opinione pubblica attraverso disinformazione.

Si tratta di hacker reclutati direttamente dai governi o dalle agenzie di intelligence, oltre a gruppi affiliati a entità statali. Queste affiliazioni si rivelano particolarmente vantaggiose quando si tratta di attribuire la responsabilità di un attacco, poiché consentono di mantenere un margine di ambiguità. In molti casi, è possibile sostenere che le accuse siano infondate o parte di una strategia di disinformazione o guerra mediatica. Esempi di questi gruppi includono:

Solo per citarne alcuni.

Un esempio emblematico è Edward Snowden, l’ex hacker della National Security Agency (NSA) degli Stati Uniti D’America che ha rivelato il programma di sorveglianza globale noto come Datagate. Le sue rivelazioni hanno portato alla luce l’estensione delle operazioni di spionaggio condotte dagli Stati Uniti, dimostrando come ogni nazione disponga di legioni di hacker pronti a impegnarsi in quella che oggi è definito come spionaggio e guerra informatica.

Dalla Russia alla Cina, dagli Stati Uniti all’Iran, il cyberspazio è diventato un nuovo teatro di conflitti globali, dove gli gli hacker possono condurre attacchi digitali per destabilizzare economie e influenzare decisioni politiche.

Infine, esiste una categoria di hacker mossi da motivazioni politiche o ideologiche: gli hacktivisti. Hacktivism (che prende forma dall’unione delle parole Hacking e Attivismo) è quella forma di protesta usata da individui o gruppi che usano le loro competenze informatiche per sostenere cause specifiche, spesso contro governi, multinazionali o organizzazioni che considerano oppressive o ingiuste.

Un esempio emblematico è Anonymous, il collettivo di hacker che opera in modo decentralizzato e si distingue per la sua maschera di Guy Fawkes. Ispirati dal film “V per Vendetta”, questi hacker hanno spaziato dalla denuncia di violazioni dei diritti umani alla lotta contro la censura, con operazioni come la protesta contro la Chiesa di Scientology o gli attacchi a siti governativi in risposta a politiche controverse.

L’hacktivismo cibernetico dimostra che l’hacking può essere un potente strumento di lotta sociale, capace di dare voce a chi si oppone a sistemi che percepisce come oppressivi. Tuttavia, come per ogni forma di hacking, l’intenzione non è sempre chiara, e le conseguenze possono essere controverse.

Curiosità, profitto e attivismo rappresentano le principali motivazioni che spingono gli hacker ad agire. Sebbene queste categorie aiutino a comprendere le diverse dinamiche dell’hacking, il confine tra esse è spesso sfumato. Gli hacker, proprio come i sistemi che esplorano, sono complessi e in costante evoluzione. Interpretare le loro motivazioni richiede uno sguardo profondo e sfaccettato, capace di cogliere sia le opportunità che i rischi di questa moderna “capacità”.

L’importanza dell’educazione alla sicurezza informatica

Come abbiamo visto, gli hacker etici e criminali condividono le stesse competenze, ma si differenziano per motivazioni, intenzioni e conseguenze. Entrambi manipolano e sfruttano vulnerabilità nei sistemi, ma il loro intento distingue gli “eroi” della cybersicurezza dai “criminali informatici”.

Gli hacker etici sono professionisti che usano le loro abilità per migliorare la sicurezza e proteggere i dati. Spinti dalla curiosità tecnologica, lavorano legalmente per enti governativi, aziende e organizzazioni non-profit. Il loro obiettivo è risolvere problemi e identificare vulnerabilità, contribuendo a rendere i sistemi più sicuri. L’hacker etico opera con il permesso del proprietario del sistema, spesso tramite attività di penetration test.

Gli hacker criminali (o “black hat”) usano le loro competenze in modo illegale, per motivi di profitto, vendetta o protesta. Violano la privacy, rubano informazioni e causano danni economici enormi. Alcuni agiscono da soli, altri all’interno di gruppi, come le ransomware gang. Il loro scopo è sfruttare le vulnerabilità a proprio favore, senza interesse per la sicurezza. Ecco alcuni degli hacker etici più noti:

Molti hacker criminali, dopo essere stati arrestati, sono riusciti a redimersi e a diventare esperti di sicurezza. Ecco alcuni dei hacker criminali più noti che sono riusciti a trasformarsi:

Questi hacker, pur avendo avuto un passato criminale, hanno trasformato le loro esperienze in una carriera positiva, contribuendo alla protezione delle infrastrutture digitali globali.

Il mondo degli hacker è complesso e sfaccettato. E’ un microcosmo dove le motivazioni, l’etica e gli intenti si intrecciano. Questo da vita a una varietà di protagonisti che spaziano dai paladini della cybersicurezza ai criminali informatici. Quello che emerge è come le stesse abilità possano essere impiegate per fini costruttivi o distruttivi, a seconda delle circostanze e delle scelte individuali.

Gli hacker etici, guidati dalla curiosità e dal desiderio di migliorare la sicurezza dei sistemi, si pongono come alleati nella lotta contro le minacce cibernetiche. Il loro lavoro è fondamentale per proteggere le informazioni sensibili e garantire il funzionamento sicuro delle infrastrutture digitali. Uun obiettivo che, in un mondo sempre più connesso, ha assunto un’importanza crescente.

Dall’altra parte, i gruppi di hacker criminali, con le loro azioni devastanti, continuano a rappresentare una minaccia concreta per aziende, governi e individui. Nonostante le differenze tra gli hacker etici e criminali, è interessante osservare come alcuni di questi ultimi, dopo aver percorso la strada della criminalità, possano riscattarsi e diventare esperti rispettati nella sicurezza informatica, dimostrando che la linea che separa i “buoni” dai “cattivi” non è sempre netta.

Nel futuro, è probabile che la figura dell’hacker continuerà a evolversi, rimanendo al centro del dibattito su sicurezza, etica e diritto digitale.

Alla fine, è l’etica che definisce la direzione delle nostre azioni, trasformando il potere della tecnologia in uno strumento di progresso o di distruzione.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…