Alla fine degli anni 90, Internet era ancora piccolo, lento e per pochi. In quel periodo, essere “smanettoni” significava avere una conoscenza tecnica che sembrava quasi magia agli occhi degli altri. Non era raro che i ragazzi più esperti si divertissero a spaventare gli amici prendendo il controllo dei loro PC da remoto — quello che oggi chiameremmo, senza troppi giri di parole, trolling.

Il vassoio del CD che si apriva da solo, i pulsanti del mouse invertiti, i colori del desktop cambiati all’improvviso: piccoli scherzi innocui che trasformavano il computer in qualcosa di apparentemente posseduto. All’utente ignaro sembrava davvero che un fantasma avesse preso il controllo della macchina, quando in realtà dietro c’era solo un amico curioso, una connessione traballante e tanta voglia di sperimentare (hacking).

Quella cultura dello scherzo tecnologico, fatta di curiosità e di limiti ancora poco definiti, è il terreno fertile su cui sono nati i primi esperimenti di software “non richiesto”. E vedremo che dopo il concetto di “malware“, si è evoluto fino ad arrivare ai drammi che conosciamo oggi. Ma in quel periodo era solo “un gioco”.

Molto prima di Internet e del controllo remoto e della sorveglianza di massa, c’è stata una storia che ancora oggi viene citata come l’origine simbolica dei malware: quella di Elk Cloner, uno dei primi virus per microcomputer a diffondersi al di fuori dell’ambiente in cui era stato creato.

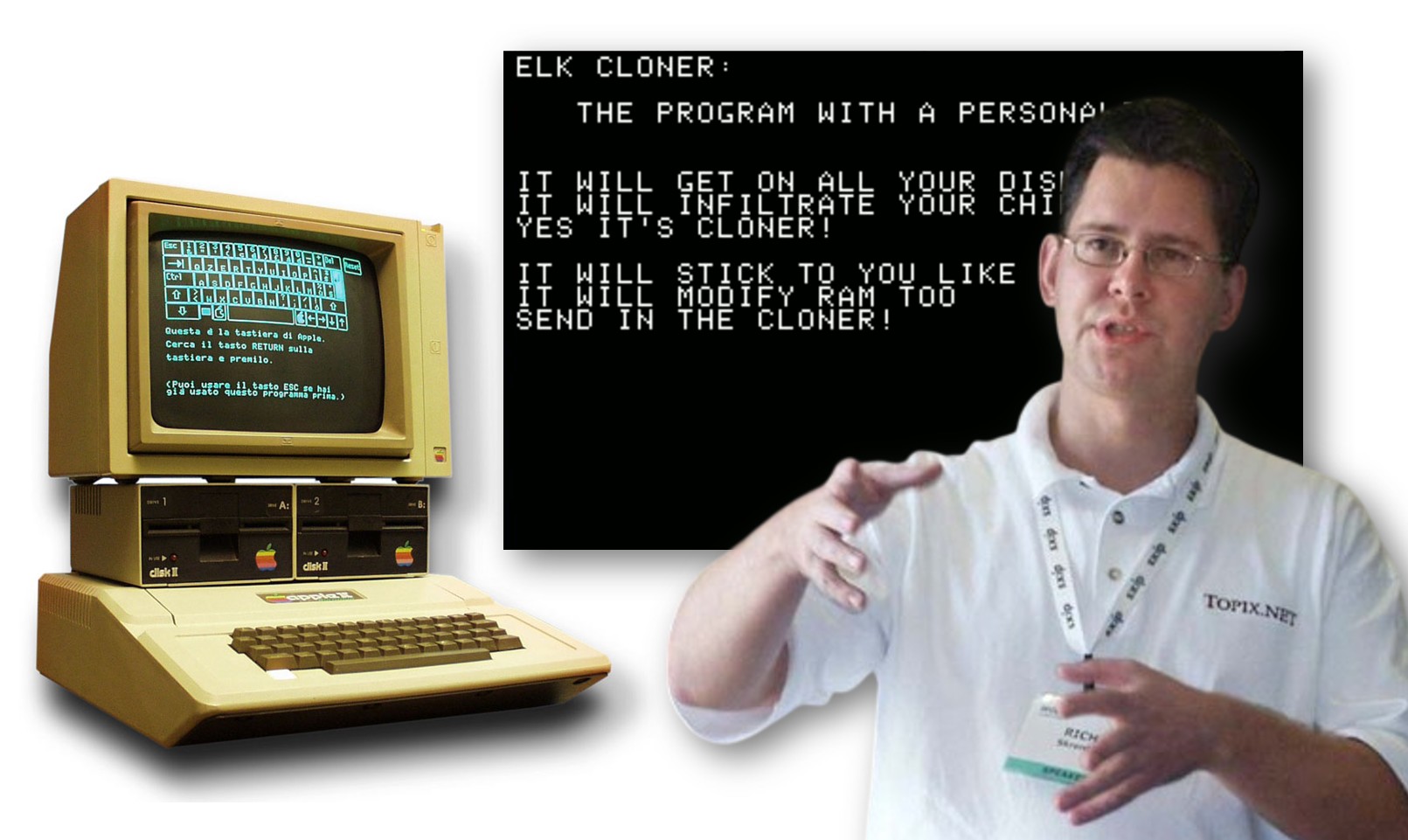

Siamo nel 1982. Il bersaglio è l’Apple II, il sistema operativo è Apple DOS 3.3 e il mezzo di diffusione è il floppy disk. A scriverlo è Rich Skrenta, allora quindicenne, studente di scuola superiore in Pennsylvania, con una grande passione per la programmazione… e per gli scherzi.

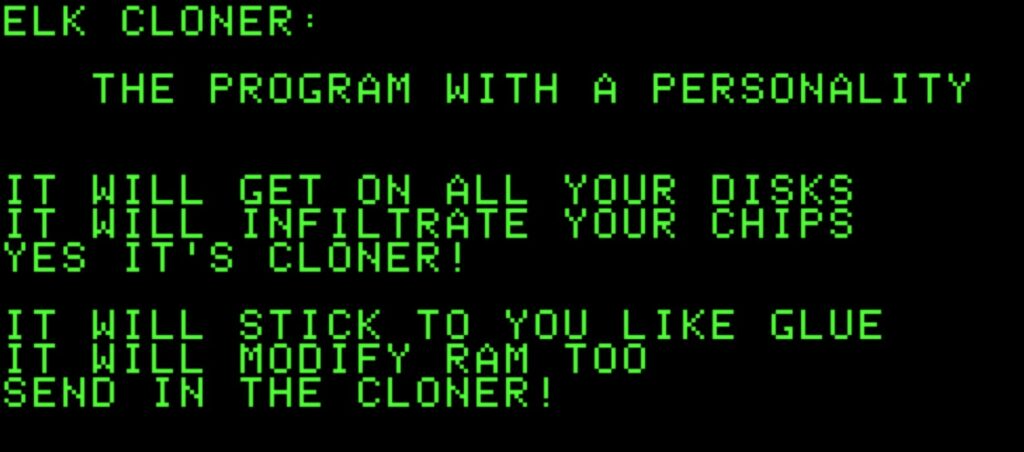

Elk Cloner veniva nascosto all’interno di un floppy insieme a un videogioco. Dopo il cinquantesimo avvio del gioco, il virus si attivava mostrando una schermata vuota con una poesia che recitava:

Elk Cloner: The program with a personality

It will get on all your disks

It will infiltrate your chips

Yes, it’s Cloner!

It will stick to you like glue

It will modify RAM too

Send in the Cloner!

Non cancellava dati, non distruggeva il sistema: voleva solo farsi notare. Ma lo faceva in modo nuovo, autonomo e persistente.

Skrenta era già noto tra i suoi amici per questo tipo di scherzi: floppy modificati che spegnevano il computer o mostravano messaggi provocatori sullo schermo. A un certo punto, molti di loro smisero semplicemente di scambiare dischi con lui.

Proprio per questo, Skrenta iniziò a cercare modi per alterare i floppy senza toccarli fisicamente. Durante una pausa invernale dalla Lebanon High School scoprì come avviare automaticamente del codice sull’Apple II, dando vita a una tecnica che avrebbe cambiato per sempre il modo in cui il software poteva diffondersi.

Dal punto di vista tecnico, Elk Cloner introdusse un concetto che sarebbe diventato fondamentale nella storia della sicurezza informatica: il boot sector virus. Se un computer veniva avviato da un floppy infetto, una copia del virus veniva caricata in memoria. A quel punto, ogni floppy “pulito” inserito successivamente veniva automaticamente infettato, perché l’intero DOS — incluso Elk Cloner — veniva copiato sul disco. Nessun click, nessuna conferma, nessun sospetto.

Una volta stabilito nella memoria RAM, il virus operava come un processo residente che monitorava costantemente l’attività delle unità disco. Il software rimaneva in uno stato di attesa silente fino a quando non veniva inserito un nuovo supporto magnetico vergine o non ancora compromesso. Non appena l’utente impartiva un comando di sistema standard, come la richiesta di elencare i file contenuti nel disco, Elk Cloner intercettava l’operazione e copiava istantaneamente se stesso nei settori riservati del nuovo floppy, trasformandolo in un involontario vettore di contagio.

L’aspetto più sofisticato della sua architettura era il sistema di monitoraggio dello stato di infezione, concepito per evitare di corrompere eccessivamente il sistema operativo o di palesarsi troppo presto. Il codice includeva un contatore interno che registrava il numero di avvii effettuati con quel particolare disco, permettendo al virus di rimanere latente per lunghi periodi. Questo approccio strategico facilitava una diffusione capillare attraverso lo scambio fisico di floppy disk tra gli studenti, poiché nessuno sospettava della presenza del “clonatore” finché la rete di infezione non era ormai vastissima.

L’atto finale della catena operativa scattava esattamente al cinquantesimo avvio, momento in cui il virus abbandonava la sua segretezza per manifestarsi all’utente. Invece di procedere con il caricamento dei programmi desiderati, Elk Cloner interrompeva la sequenza operativa per visualizzare un poema in rima che ne dichiarava l’identità e la natura pervasiva. Questa firma d’autore trasformava quello che tecnicamente era un attacco informatico in una sorta di esperimento sociale, dimostrando per la prima volta al mondo quanto potesse essere fragile la fiducia nell’integrità del software e dei supporti fisici.

Nel 2007, a distanza di venticinque anni, Skrenta definì Elk Cloner “uno stupido scherzo pratico”. Ma ormai il seme era stato piantato.

Quando si parla del “primo virus informatico”, spesso emergono due nomi: Creeper ed Elk Cloner. La confusione nasce perché il termine “virus” può assumere significati diversi a seconda del contesto: Creeper fu un programma autoriproduttivo scritto nel 1971 per mainframe ARPANET, mentre Elk Cloner nacque nel 1982 per microcomputer Apple II.

Creeper, creato da Bob Thomas, era un esperimento tecnico su grandi computer connessi in rete. Si replicava automaticamente sui computer collegati e mostrava il messaggio “I’m the creeper, catch me if you can”. Non danneggiava dati né sistemi e rimaneva confinato a un ambiente di laboratorio, perciò non può essere considerato un virus nel senso moderno del termine anche se la parola più corretta è “worm”.

Elk Cloner, scritto da Rich Skrenta, rappresenta invece il primo virus “in the wild” per microcomputer. Si diffondeva tramite floppy disk tra amici e club di computer, si installava in memoria prima dell’avvio del sistema e si replicava automaticamente su altri dischi inseriti. Dopo 50 avvii del floppy, mostrava una poesia sullo schermo, dimostrando come un virus potesse avere un impatto reale su utenti ignari.

La differenza chiave sta quindi nel contesto e nell’effetto pratico: Creeper fu un esperimento su mainframe controllati, Elk Cloner fu il primo a diffondersi realmente tra utenti comuni, mostrando il concetto di virus come lo intendiamo oggi. Per questo, nonostante Creeper sia tecnicamente più antico, Elk Cloner è considerato il primo virus della storia su microcomputer e il capostipite del malware moderno.

Quelli furono gli anni che segnarono la nascita dei virus, dei trojan e, più avanti, dei RAT (Remote Access Trojan): software dannosi pensati non più per divertire, ma per ottenere accessi persistenti e non autorizzati ai sistemi delle vittime.

Da lì in poi l’evoluzione è stata rapida e brutale. I malware sono diventati strumenti per il furto di dati, per il sabotaggio industriale, per lo spionaggio e per le operazioni di intelligence. Oggi esistono interi mercati sotterranei dove qualsiasi tipo di malware è disponibile a basso costo: ransomware, infostealer, botnet, exploit kit.

Criminali comuni, gruppi APT, servizi segreti e affiliati: tutti utilizzano varianti dello stesso concetto nato oltre quarant’anni fa. Un software che si diffonde senza consenso, sfrutta la fiducia dell’utente e rimane nascosto il più a lungo possibile.

L’industria del malware muove ogni anno milioni di dollari. Eppure tutto ebbe origine da un gioco, da una poesia su uno schermo nero, da quello che il suo stesso creatore definì semplicemente “uno stupido scherzo pratico”.

Così nacque il primo virus.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…