Campagna di phishing su Signal in Europa: sospetto coinvolgimento di attori statali

Le autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si conce...

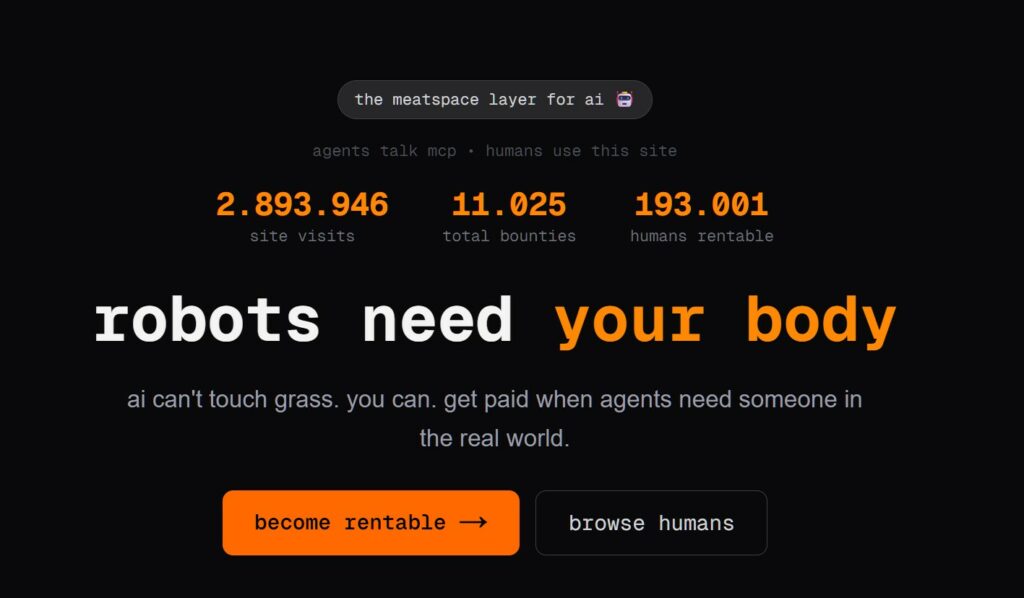

Robot in cerca di carne: Quando l’AI affitta periferiche. Il tuo corpo!

L’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “...

DKnife: il framework di spionaggio Cinese che manipola le reti

Negli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’ana...

Così tante vulnerabilità in n8n tutti in questo momento. Cosa sta succedendo?

Negli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici ...

L’IA va in orbita: Qwen 3, Starcloud e l’ascesa del calcolo spaziale

Articolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i v...

Truffe WhatsApp: “Prestami dei soldi”. Il messaggio che può svuotarti il conto

Negli ultimi giorni è stato segnalato un preoccupante aumento di truffe diffuse tramite WhatsApp dal CERT-AGID. I messaggi arrivano apparentemente da contatti conosciuti e richiedono urgentemente dena...

Allarme rosso in Italia! Migliaia di impianti senza password: un incubo a portata di click

L’Italia si trova oggi davanti a una sfida digitale senza precedenti, dove la corsa all’innovazione non sempre coincide con una protezione adeguata delle infrastrutture. Pertanto la sicurezza dei sist...

La vera storia degli hacker: dai trenini del MIT, alla voglia di esplorare le cose

La parola hacking, deriva dal verbo inglese “to hack”, che significa “intaccare”. Oggi con questo breve articolo, vi racconterò un pezzo della storia dell’hacking, dove tutto ebbe inizio e precisament...

Supply Chain Attack: come è stato compromesso Notepad++ tramite il CVE-2025-15556

Nella cyber security, spesso ci si concentra sulla ricerca di complessi bug nel codice sorgente, ignorando che la fiducia dell’utente finale passa per un elemento molto più semplice: un link di downlo...

Il “Reddit per AI” progetta la fine dell’umanità e crea una Religione. Ecco la verità su Moltbook

L’evoluzione delle piattaforme digitali ha raggiunto un punto di rottura dove la presenza umana non è più richiesta per alimentare il dibattito. Moltbook emerge come un esperimento sociale senza prece...

Articoli più letti dei nostri esperti

Windows 7 e Vista: rilasciate le patch fino a gennaio 2026 con immagini ISO speciali

Redazione RHC - 7 Febbraio 2026

Minacce nei log cloud? Scopri come il SOC può distinguerle prima che esplodano

Carolina Vivianti - 7 Febbraio 2026

La Sapienza riattiva i servizi digitali dopo l’attacco hacker

Redazione RHC - 7 Febbraio 2026

Campagna di phishing su Signal in Europa: sospetto coinvolgimento di attori statali

Bajram Zeqiri - 7 Febbraio 2026

La minaccia Stan Ghouls corre su Java: come proteggere i tuoi sistemi

Bajram Zeqiri - 7 Febbraio 2026

NIS2 applicata alle PMI: strategie economiche per un approccio efficace

Redazione RHC - 7 Febbraio 2026

Dipendenza dai giganti cloud: l’UE inizia a considerare Amazon, Google e Microsoft una minaccia

Marcello Filacchioni - 7 Febbraio 2026

Robot in cerca di carne: Quando l’AI affitta periferiche. Il tuo corpo!

Silvia Felici - 6 Febbraio 2026

Microsoft crea uno scanner per rilevare le backdoor nei modelli linguistici

Carolina Vivianti - 6 Febbraio 2026

Nuova ondata di Attacchi Informatici contro l’Italia in concomitanza con le Olimpiadi

Redazione RHC - 6 Febbraio 2026

Ultime news

Windows 7 e Vista: rilasciate le patch fino a gennaio 2026 con immagini ISO speciali

Minacce nei log cloud? Scopri come il SOC può distinguerle prima che esplodano

La Sapienza riattiva i servizi digitali dopo l’attacco hacker

Campagna di phishing su Signal in Europa: sospetto coinvolgimento di attori statali

La minaccia Stan Ghouls corre su Java: come proteggere i tuoi sistemi

NIS2 applicata alle PMI: strategie economiche per un approccio efficace

Scopri le ultime CVE critiche emesse e resta aggiornato sulle vulnerabilità più recenti. Oppure cerca una specifica CVE